Tuesday Reads ( Vol 3), 25 June 2019

Dear Reader,

I have just finished reading Amitav Ghosh’s magnificent novel Gun Island. It is about Dinanath Datta, a rare books seller whose life gets entangled with an ancient legend about the goddess of snakes, Manasa Devi. It is a fascinating story that begins in the Sunderbans to New York to Venice. Gun Island has a fantastic cast of characters but it is also a story very relevant to our times for its focus on the situation of migrants and climate change.

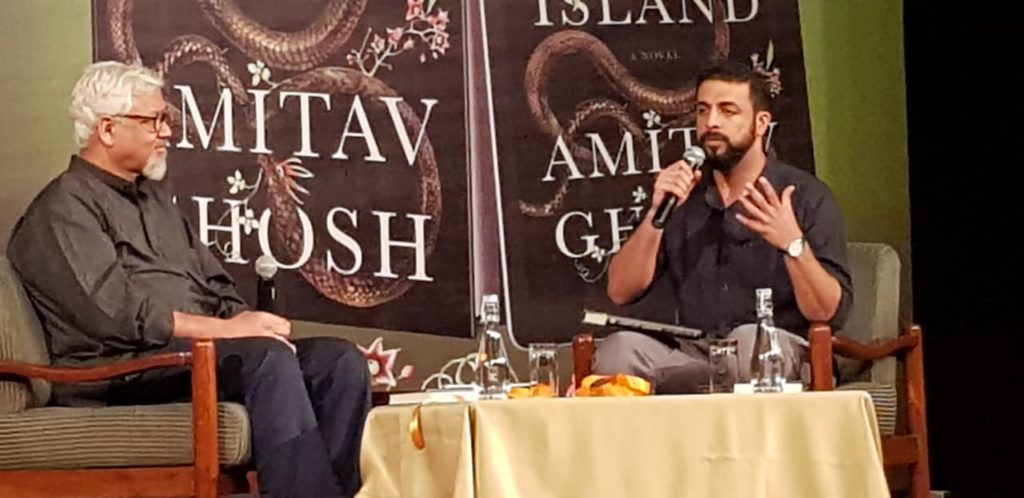

At the New Delhi book launch held on 13 June 2019, India Habitat Centre, Amitav Ghosh was in conversation with Raghu Karnad. It was a very special evening as it occurred two days after the untimely demise of the playwright, Girish Karnad. So the book launch morphed into this public memorial for Girish Karnad too. It began with the new Jnanpith winner Amitav Ghosh’s tribute to another Jnanpith winner Girish Karnad. The conversation began with Raghu Karnad, son of Girish Karnad, saying, “My father was a chronicler of Karnataka and of this country, I consider you to be a chronicler of this planet. Interconnecting the countless parts we are in the midst of but miss. They are forces of language, war, or even eco-system.” These opening remarks triggered off a fascinating conversation about “unlikely coincidences” and “meaningful resonances” that exist between space and time. Also what does it mean to try and rationalise events that defy rationalist thinking but at times it is impossible to do so. A significant proportion of Gun Island dwells upon the global migrant crisis. During the conversation Amitav Ghosh commented that “the central literary question is how do you talk about the slow violence that eats itself into peoples lives and never finds its way into newspapers? In the papers every day there are so many reports about violence but this slow violence does not get attention. We have learned to turn our eyes away from it. The issue is how do we find ourselves back to recognise the violence unfolding around us. Poetry is better able to respond to the catastrophe and cataclysm we see around us. Poetry does not have that commitment. Poetry has always responded to every natural event. You see it in Byron and in pre-modern Indian poetry which is not poetry for the sake of poetry — it is devotional. We have to find ourselves back to that…back to being able to talk about other things apart from us.”

Gun Island is an unputdownable book. It will sell well but more so because of the old fashioned word-of-mouth recommendations. At the book launch there were whispers overheard of Amitav Ghosh probably being a contender for the Nobel Prize for Literature in the coming years. Who knows?! But for now it would be interesting to see if this book makes it to the shortlist of the more prominent literary prizes around the world like The Booker Prize. It is certainly a book that cannot be ignored!

Of all the books I read in the past week Gun Island was exceptional.

More anon,

JAYA

25 June 2019