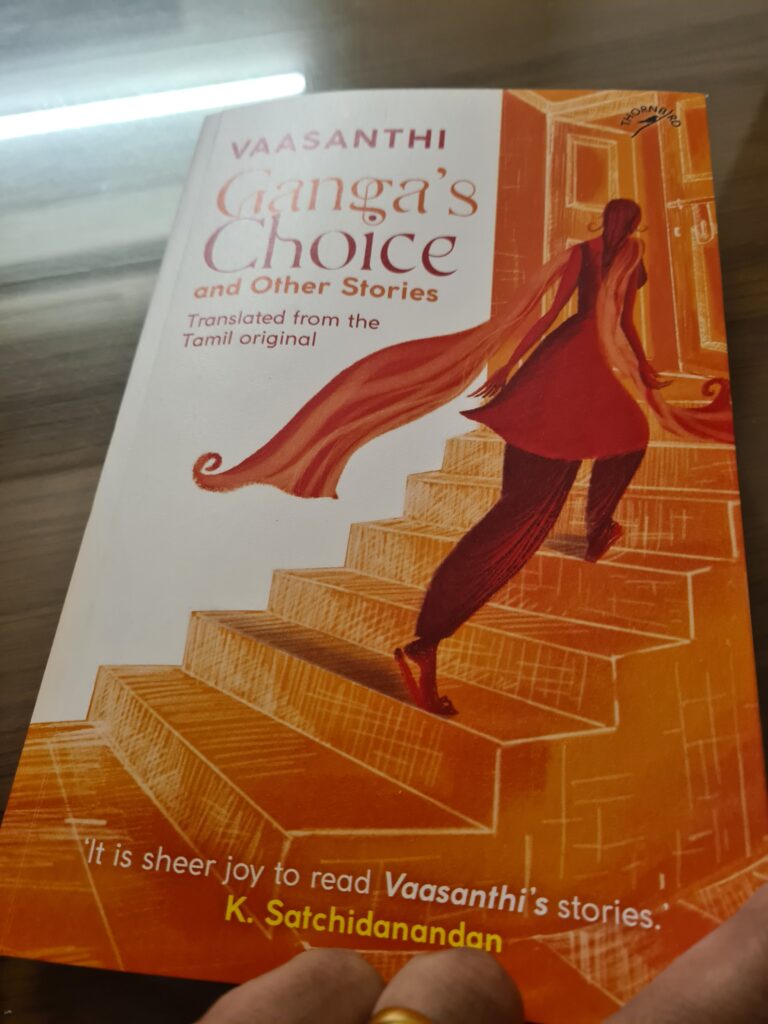

“Ganga’s Choice and Other Stories” by Vaasanthi

Tamil writer and journalist Vaasanthi’s collection of short stories Ganga’s Choice and Other Stories is mixed bag ( Niyogi Books). While the title indicates that the stories are in all likelihood womencentric, but it is not so. The stories are by a woman writer with a very strong sense of empathy for her characters, human rights and justice. The title story is bold even though it should not be— the protagonist asserts her right to be single, not forced into marriage or hand over the title deed to her one-room tenement to a prospective suitor. In womens movements, this idea of choice is a strong option and depending on how it is exercised, is viewed either favourably or not by feminists. In this story, feminists will approve of Ganga opting to live life on her own terms. If she had made the choice to capitulate to marriage and patriarchal notions of the man usurping her property, then it would not have been viewed kindly. But it is precisely these scenarios that make the concept of choice in the third wave of feminism problematic for many. The free will of the individual/woman is barely taken into consideration unless the woman chooses for the “right” way. Be that as it may, “Ganga’s choice” is predictable but it is necessary for such stories to be repeated over and over again as they are empowering for the readers. It offers a way of existence.

The other stories in the volume are more varied. “The Testimony” is a disturbing short story about a young woman seeking justice from the courts regarding the lynching of fourteen members of her family but having to retract her testimony at the last minute. She does it to save the lives of her mother and younger brother after receiving death threats. Also, after realising that the perpetrators have bought over the entire machinery of law enforcement officers, witnesses and legal entities. A single woman is helpless in such a situation. Two other stories that stand out are “He Came” and “The Line of Control” that have a strong journalistic flavour. In the tradition of best reportage, real events are repeated in the form of a story. “He Came” is most definitely based on a true event that took place at the beginning of the pandemic when two migrant workers, a Muslim and Hindu, best friends from childhood began the trek home. On the way, the Muslim got Covid and was very sick, but his friend looked after him. The patient had to be hospitalised and his friend stayed with him. Unfortunately, he died. Vaasanthi’s moving short story is more or less similar to this real story although she never acknowledges it being based on the incident. I remember the story from the beginning of the pandemic. It stood out. “The Line of Control” is about a young Muslim boy, Akbar, rescued by his Sikh neighbour, Jagat Singh, who had lost his family in cross-border firing, but never nursed anger for the other. Even though his “friends” like Somnath “parroted” what they had been told regarding the “enemy” —

“No matter who the perpetrator of the crime , that fellow is your enemy.”

…

“He is your enemy; His religion is your enemy.”

Enshrining real incidents such as these in short stories are a fine example of our Indianess, our secular fabric, our gender equality as enshrined in our Constitution by granting universal franchise. If the goal is that narratives will never be forgotten despite external factors trying to create a divisive society, then these stories are effective.

While the stories are a repository of our society in flux and an attempt to capture details, the book itself is a textbook case study of publishing translations. There are three translators involved in this project— Sukanya Venkataraman, Gomathi Narayanan and Vaasanthi. Yet, none of them are mentioned as translators on the book cover or title page. Nor does the copyright page mention Venkataraman or Narayanan. The copyright for text and translation rests with Vaasanthi. The relevant translator is acknowledged at the end of every story and Vaasanthi also graciously mentions them on the last page. But this lack of clarity about the relationship between author and translators is unacceptable. If the translations had been commissioned then it should be clearly mentioned. This is probably the case since the translators seem to have relinquished their rights as evident in the copyright page. Even if the translators did not sign a publishing contract for this book, in the interests of good publishing practice, they should have been mentioned on the book cover. This is one of the fundamental demands of translators worldwide to be given due recognition in the destination language. This is not a difficult request to accede to. Apart from which it accords everyone in the editorial team equal respect. It is worth considering.

Read Ganga’s Choice and Other Stories . It is obvious that many of these stories are going to find their way into supplementary readers for schools and colleges. Decide for yourself.

5 Feb 2022