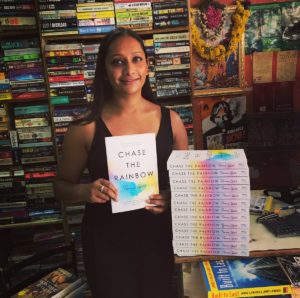

Tuesday Reads ( Vol 6&7), 23&30 July 2019

Dear Reader,

This is a double issue as time whizzed by before I knew it, the week was over!

As the book fairs, literature festivals and literary awards season draws near, the number of titles being released into the market increase exponentially. Some of them being the “big titles” that the publishing firms are relying upon. Two of them featured here are two such titles. These are the thrillers — The Flower Girls by Alice Clark-Platts and The Silent Patient by Alex Michaelides.

Alice Clark-Platts, founder of Singapore writers group and a former human rights lawyer, has published her third thriller. The Flower Girls is about the killing of two-year-old girl by two sisters, who are six and ten, respectively. It is a case that had caught the imagination of the media. The older sister had been incarcerated but the younger one had been let off as she was too young to be tried. Instead the police force helped the parents and remaining daughter to assume new identities and start a new life in a different city. Two decades later the case is recalled as another five-year-old girl goes missing. It is an absorbing tale for its details of the murder and trial that seem to defy human imagination. It is as if there is an underlying truth to the horrors a human being is capable of, almost as if it is the transferance to some extent of a lived experience by the author to the page, but not necessarily a replication of any case she has dealt/read. Apart from the horror of the actual crime itself, there are many pertinent issues raised in this novel about the troublesome aspect of incarcerating one so young, arguments for parole, the course of justice and the prejudices people may have that may colour their judgement. The best discovery in this novel is the creation of DC Hillier, almost as if she is the female response to Jack Reacher or a modern reincarnation of Miss Marple. The potent combination of a fine instinct for sniffing out criminals built over many years as a Detective Constable, phenomenal memory, dogged persistence to pursue clues, and a fascination for being first on the crime scene, make DC Hillier a character worth following in the coming years. Her beat will remain unchanged. It will be the small town but there will be plenty of opportunities for stories to occur as tourists visit the seaside. Since The Flower Girls is her first appearance on the literary landscape, DC Hillier will take at least another 2-3 novels before she settles down, but once she does, she will soar!

Rating: 4.5 / 5

Debut novelist Alex Michaelides’s The Silent Patient is already an NYT bestseller. It’s first print run was 200,000. It is a psychothriller that is gripping. It moves swiftly. There are short sentences, crisp dialogue and the length of the chapters match the smart pace of the storytelling. It helps that the author studied English literature at Cambridge University and earned his MA in screenwriting at the American Film Institute in Los Angeles. This professional training has helped create an undeniable page turner. All those who have endorsed the book, such as Lee Child, David Baldacci, Joanne Harris, Stephen Fry, and C. J. Tudor, are absolutely correct in their assessment of it being an excellent, slow-burning psychological thriller. It is about Alicia Berenson who is accused of killing her fashion photographer husband Gabriel. No one knows why she did it since after shooting him in the face she stops talking. After trying to attempt suicide, she is taken into custody and then sent off to asylum called The Grove. The story is narrated by forensic psychotherapist Theo Faber whose opening introduction about himself is that he “was fucked up”. He is offered an appointment at The Grove and becomes Alicia’s therapist. It is a gripping tale undoubtedly and no wonder it has already been sold into 39 territories and is being developed into a major motion picture. Be that as it may, there are details in the story that give it away as amateur work that will go largely unnoticed with most readers. For instance, when Alicia hands over her diary to Theo Faber to read, he says that judging by the handwriting, it was written in a chaotic state of mind, where the writing was barely legible and doodles and drawings taking over some of the pages. Yet, the diary extracts reproduced in the story are beautifully composed with complete sentences, perfect dialogue, smooth narration and build the plot seamlessly. A bit puzzling given how Alicia is known to be of troubled mind. Later too as the plot hurtles to the end, the inexplicable switch in the timelines while acceptable when the reader is in a reading haze, are bothersome details when reflecting upon the story later. It is unfair to the reader for the author to switch timelines as if for convenience to tie up the loose ends in the plot. This is a novel that has possibly been written with a view to adapt it to the screen and the magic has worked. It is to be seen if the subsequent novels of Alex Michaelides will inhabit this dark and depressing world. Whatever the case, Alex Michaelides’s brand of psychothriller, is here to stay and will spawn many versions of it too.

Rating: 3.5/5

The third book is a collection of short stories by Indian women writers called Magical Women, edited by Sukanya Venkatraghavan. It is a pleasant enough read if read with zero expectations about reading fantasy stories that take strong imaginative leaps into a magical realm. Most of the stories are pleasant to read. The stories are preoccupied with worries of the real world such as of sexuality, child molestation, infidelity, etc. Two stories that stand out are “Gul” by Shreya Ila Anasuya and “The Rakshasi’s Rose Garden” by Sukanya Venkatraghavan. “Gul” is about a nautch girl during the uprising of 1857 and “The Rakshasi’s Rose Garden” is about child molesters. While most of the stories in the collection have immense potential, they tend to fall flat on their face for the inability of the writers to lift it off the ground with elan. Instead most rely on done-to-death details as pods and strange creatures. When the story is to take an imaginative leap it lands straight into a world that is a mere transplantation of existing reality or the world of mythology. So there is a rave party, a mysterious laboratory, lesbians, etc. There is nothing truly breakaway in Magical Women except for the fact that it is a breakaway collection of talented storytellers who may one day astound the world with their true potential. For now, most of them, are holding back. I wonder why?

Rating: 3.5/5

And then there is The Man with the Compound Eyes by Taiwanese author Wu Ming-Yi, translated by Darryl Sterk. An eco-fiction that Tash Aw in his 2013 review in the Guardian referred to it as hard-edged realism meets extravagant fantasy.

It is easy to see why Wu’s English-language publishers compare his latest novel to the work of Murakami and David Mitchell. His writing occupies the space between hard-edged realism and extravagantly detailed fantasy, hovering over the precipice of wild imagination before retreating to minutiae about Taiwanese fauna or whale-hunting. Semi-magical events occur throughout the novel: people and animals behave in mysterious ways without quite knowing why they are doing so; and, in a Murakami-esque touch, there’s even a prominent cat. But beyond these superficial similarities lies an earnest, politically conscious novel, anchored in ecological concerns and Taiwanese identity.

Encapsulating such a rich novel is not easy but suffice to say it that the author’s environmental activism, trash in the sea, concerns about climate change, a deep understanding of environmental disasters, has helped him create an extraordinarily fantastic novel. From the first sentence it immediately transports the reader into this magical world of the imaginary island of Wayo Wayo, created with its own myths and folk legends. Fantastic novel that years after the English translation was made available, it continues to find new readers, with new translations.

Rating: 4/5

The final book is Leaving the Witness: Existing a Religion and Finding a Life, a memoir by a former Jehovah Witness, Amber Scorah. It is an account of Amber’s life as a Jehovah Witness, finding a husband from the same community and then travelling across the world to become missionaries in China. Amber knew Mandarin so could speak to the locals. Her grasp of the language improved as she began to communicate more frequently with others. She managed to get a job working on podcasts, at a time when podcasts were barely heard of, and yet her shows became so popular that Apple ranked it amongst the top 10 podcasts of the year. While in China, she befriended many outside the community, even made friends like Jonathan online, but kept it a secret from her husband and their circle as this was considered taboo. Soon she begins to question her proselytising as questions are raised of her regarding her beliefs. She is forced to question her blind faith in the cult. Slowly her marriage disintegrates too. Leaving the Witness reads like her testimony, a reaffirmation of her belief, except not entirely in the manner that her church would have approved. Amber Scorah chooses to leave the community and build a life of her own. It is tough for she has to learn how to make friends, she has to learn simple things like understanding popular culture references in casual conversation, being able to enter and enjoy a social engagement without feeling horribly guilty etc. It ends sadly with the death of her infant son at the daycare centre but it also is a strong testament to others wishing to leave suffocating environments that it is possible to do so and build new lives. It is not easy but it is possible. In fact the book has been placed on O, The Oprah Magazine Summer 2019 Reading List and Trevor Noah invited Amber Scorah to his talk show. It is a good book and deserves all the publicity it can garner.

Rating: 4.5/5

Happy Reading!

JAYA

30 July 2019