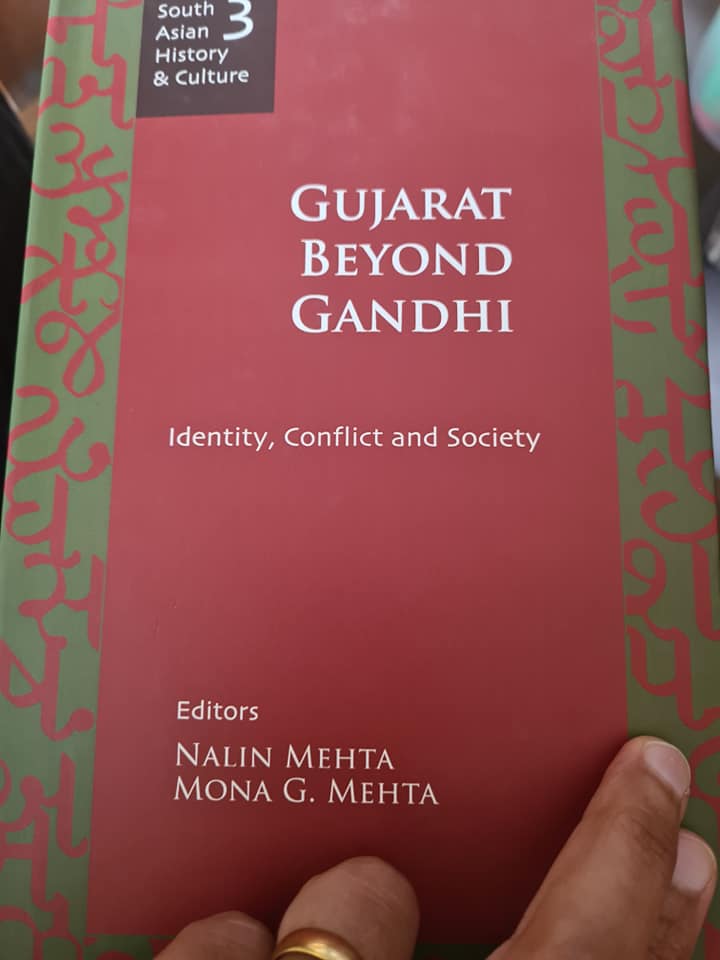

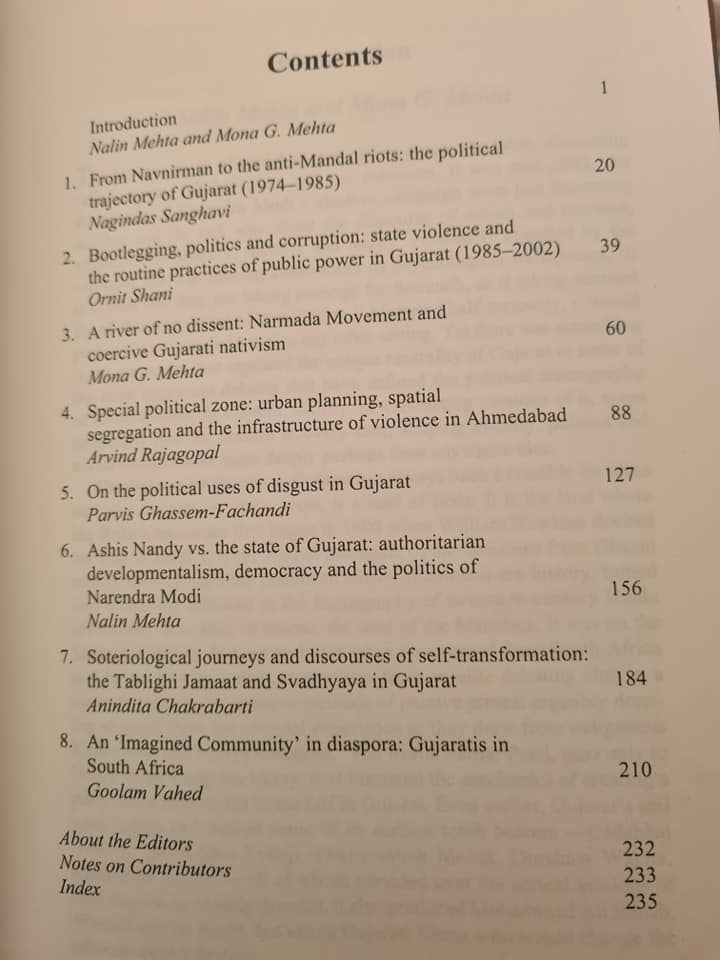

“Gujarat beyond Gandhi: Identity, Conflict and Society”

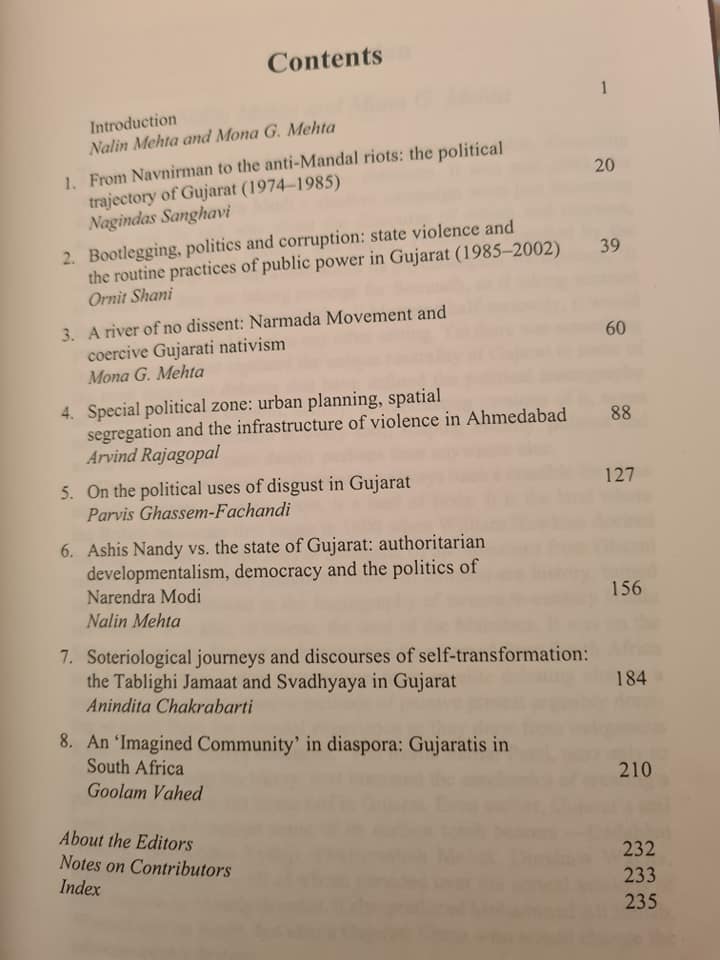

Published in 2010 by Routledge, Gujarat beyond Gandhi: Identity, Conflict and Society, edited by Nalin Mehta and Mona G. Mehta is worth reading a decade later. The essays in the volume are varied and pick on different aspects of Gujarat. But it is the essay by Nalin Mehta that is truly worth spending time over. Much of what he documents at the state level is now being played out at the national level. Entitled “Ashis Nandy vs. the state of Gujarat: authoritarian developmentally, democracy and the politics of Narendra Modi”, Mehta plots in a detailed manner how this case against Nandy was filed by a “private citizen” against Nandy and Times of India (2008), where an article bemoaning the ‘culture of Gujarat politics’ and the middle classes for the state’s communal division, had been published. TOI distanced itself from the case. Nandy pointed out that this was a far cry from his experience with Khushwant Singh as the editor of Illustrated Weekly who fought the case slapped against them. Anyway, as Mehta adds, this “was a unique battle that was crucial for Indian public life across several different registers”. Prescient observation.

Reflecting on the issues raised by the case, Nandy rightly went on to argue that it was symptomatic of a larger Emergency-like culture and a disconnect with liberal cultures of intellectual dissent:

I was surprised because of the flimsiness of the case. I was surprised by the instances they cite in the police notice . . . they are not only trivial, they are comical. . .

This book, especially this essay, deserve to be resurrected from the graveyard of prohibitively expensive academic publications and made available to a wider audience. Conversations that essays like this can trigger must happen in real time and not decades later. Analyse. Debate. Discuss. Most importantly, testimonies such as this by people who have witnessed significant socio-political events and offered their opinion immediately, ensure that living histories are extensively shared and may perhaps unleash other memories. People will not feel isolated. Also, a collective feeling of sharing an experience may help develop a life force of its own to battle destructive energies.

Read this essay, if you can.

2 Feb 2021