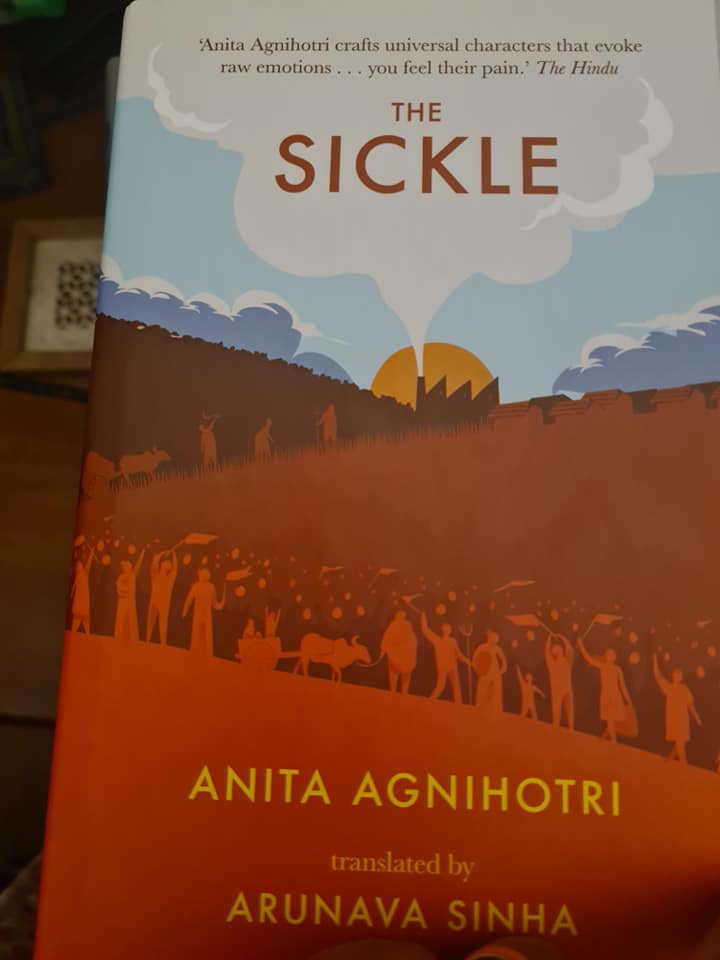

Anita Agnihotri’s”The Sickle”, translated by Arunava Sinha

The Sickle by Anita Agnihotri, translated by Arunava Sinha is a very powerful story. It is hard to believe that it is pure fiction. There are far too many instances in the book that seem like a thinly veiled account of reality. For instance:

The sugar mill owners had in fact opened up a toddy shop right here inside the toli. There may not have been taps or toilets, water for bathing, or a dependable roof over one’s head, but the men still dropped in to drink on their way back to their shanties. It was the only way to get rid of their aches and pains. …The men weren’t concerned about how the women managed to keep their households running in the toli. No matter how hard they worked, they would never have hard cash since they had taken their payment in advance. And yet they needed flour and rice, vegetables and kerosene. And it was the women who would have to do the cooking. What they did was save the tips of the sugarcane stalks, which had no juice but only leaves, from the acquisitive hands of the farmers and sell them for a little money. The inhabitants of the districts on the West turned up here to buy cattle fodder and kindling. From sugarcane leaves to slices sugarcane bristles, all of it could be sold. …

The kitchens in the banjari households are under the control of women. It is the men who say this proudly. Of course, they’re the ones who continue to keep the women behind the veil. From leaving the house to going to high or college, it all depends on the whims of the menfolk. But their writ doesn’t run in the kitchen. Many banjari kitchens don’t allow meat or fish. The men are not permitted to bring any home, though they can eat it elsewhere. But they cannot enter the house immediately after eating meat — summer or winter, a man’s wife must upend a bucket of water over his head first to purify him.

The kitchen’s in your hands — this is how the banjari men boast. In behaviour, rituals and modes of worship, they have fashioned themselves after the Maratha community. Which is hardly a tall order. Running the kitchen means that everything from fetching the water to getting hold of kerosene, vegetables, flour and rice is the headache of the women. They are shackled for life in exchange for the privilege of being able to pour a bucket of water over their huabands’ heads now and then. The implication? Whether at home or in the toli, the husband will never check on whether there are enough provisions, or where the kindling is coming from. The woman calls the man malak, for malik, her lord and master.

Somethings never change. Anita Agnihotri, an ex-bureacrat, is known for depicting social realism in her novels. One of the responsibilities she held was member secretary of the National Commission for Women. She retired in 2016 as Secretary, Social Justice Department, Government of India.

The Sickle is set in the Marathwada region of India. This novel about migrant sugarcane cutters emerged after extensive conversations with farmers, activists, women leaders, students, researchers and young girls from Marathwada, Vidarbha and Nashik. She also consulted Kota Neelima for her research on farmers suicides. The details that are in the novel range from the horrors of sexual violence where women are preyed upon by the men as the shanties that they live in are flimsy structures and do not provide any security. Another form of sexual violence is that the women are actively encouraged to have hysterectomies, so that they do not impede the work flow by absences due to menstrual pain or more pregnancies than are necessary. The drought afflicting the region, the corruption that runs so deep that economic exploitation has become a way of life, even if it is unjust, are narrated in all their brutal honesty. As Anita Agnihotri said in a recent interview to The Mint:

In our profession, we were told, ‘If you see something, don’t carry it back’,” …. “But I followed precisely the opposite advice as a writer.” Just as there can never be a “non-committal bureaucracy,” she adds, “there is no non-political writing.

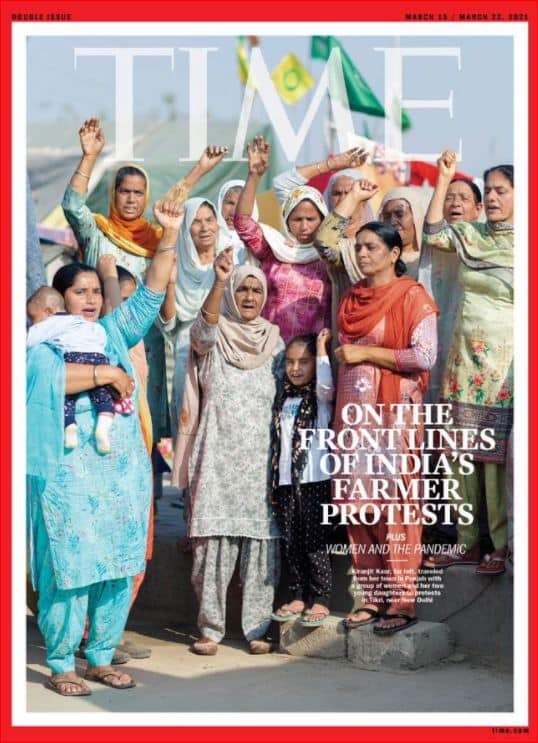

The Sickle can only be read in small doses as it is extremely disturbing in the truth it portrays. This is not going away in a hurry. Hence, it is unsurprising that the anger welling up in the ongoing farmers protests in Delhi ( on other farming related issues) is summed up by the image of women farmers on the cover of TIME magazine. It was published to commemorate Women’s Day. But the equal rights and liberties that women seek is a long time coming as Anita Agnihotri shows — the patriarchal attitudes towards women are deeply embedded in society. Such systemic violence can be combated but for it to be completely done away with is still a distant dream. It is a long and at times a debilitating struggle, but it is worth fighting for.

Read The Sickle. It has been translated brilliantly by Arunava Sinha .

25 March 2021