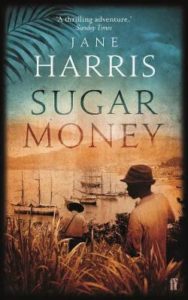

Jane Harris’s “Sugar Money”

‘All those slave, the friars bought with borrowed money.’

‘All those slave, the friars bought with borrowed money.’

‘Who told you that?’

‘Father Prudence, years agone. They took a loan from the French government and another from another merchant in London. Being the case, the French authority might say those Fort Royal slaves and their descendants belong to them. The London merchant might say the same. Of course, the friars would argue otherwise but some would say they lost the right to the slave because of the debt and their misdoings.’

‘They might have repaid those loans since.’

‘No,’ Emile replied. ‘I asked around St. Pierre the other night. They never repaid one sou, to this day. Everybody knows they are in debt from Salines to St. Domingue. That’s why they want those slave back, to grow more cane. Cane is sugar, sugar is money. That’s all we are to them. But loan or no loan, the English will care not one farthing. Now they rule the land of Grenada, they must surely lay claim to the slaves at the hospital. And if we take Celeste and the rest without permission, those Goddams will say we stole them.’

Jane Harris’s third novel Sugar Money has been shortlisted for The Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction 2018. It is set in 1765 when two brothers Emile and Lucien are charged by their French master, Father Cleophas, to return to Grenada and smuggle home forty-two slaves claimed by English invaders ( commonly referred to as “Goddams”) and working at the hospital. It is a tricky mission as there is the constant danger of the two brothers being caught. Since the two brothers are slaves themselves they have no option but to obey. Emile is under no illusions about how dangerous the mission is but is tempted to return to Grenada for he can meet his sweetheart Celeste. The action-packed novel spread over a few days is narrated by the younger brother Lucien who was taught English by a Scotsman working at the Grenada hospital. The French friars want “their” slaves back as they need help to till their cane sugar plantations in Martinique.

In the Afterword Jane Harris elaborates upon the true incident which inspired her story.

In 1738, the French Colonial Government in Grenada built a hospital overlooking the main town of Fort Royal (now known as St George’s). By 1742, the hospital had been handed over to the care of a band of mendicant monks or friars: the Brothers of Charity of the Order of St John the God — les Freres de la Charite — who had been running a hospital in the neighbouring island of Martinique for almost a hundred years. the friars looked after the sick but, in order to fund their charitable works, they also ran plantations alongside their hospitals — plantations which relied on the labour of enslaved people. The poverty-stricken friars took out loans in order to purchase these slaves, some of whom they trained as nurses to work alongside them in the hospital. the rest of the slaves were set to toil on the plantations, growing indigo and sugar cane. …the British invaded Grenada in 1763 and took over the hospital.

She continues that in August 1765, one of the mendicant friars, Father Cleophas, travelled from Martinique to Grenada in an attempt to persuade the slaves to return with him. Unfortunately he was discovered by the English and asked to leave. After which he persuaded a “mulatto” slave to go on a mission for him. It was disastrous as the English once again discovered the plan and prevented most of the slaves to escape. Of the 11 who did to Martinique had to return to Grenada and they saved themselves by blaming the mulatto slave. As a result he was the only one made an example of and hanged.

Sugar Money is an absorbing read with some truly horrific descriptions of how the slaves were treated by their masters. The brutal violence is relentless with the slaves living in constant fear. It is a story that is truly horrifying for what happened in the past but also with the knowledge that such situations continue to exist in many parts of the world even now*. It may not always be the colonial master and slave relationship but many people are being exploited in a similar fashion for purely business gains.

In an interview Jane Harris clearly states what set her off on this quest to write this historical fiction. Also being acutely aware of her white privilege; a fact which is good to know particularly in an age where conversations about cultural appropriation are constantly being resurrected.

Of course, I was – and am – very aware of my white privilege and did ask various friends, writers of colour, if they thought I was crazy to tackle such a subject. They told me that yes, I probably was crazy – but as long as I did it well enough, it wouldn’t matter. So, that was the challenge; I knew I’d have to write a good book.

She adds:

Research is crucial. It begins when I have the idea for a novel and carries on all the way through to the final draft, even to proof-stage. I’m one of those writers who likes to be as historically accurate as possible, so the research never ends. However, I’m also a great believer in ‘hiding’ the research. Your research notes shouldn’t be visible to the reader. If a fact isn’t relevant to the story then, really, it shouldn’t be in the book.

Even though The Observations is entirely a work of imagination, not based on true events, the period detail still has to be accurate. Gillespie and I is also a work of imagination, set in the art world of Scotland in the late 1880s, at the time of the International Exhibition, and so I had to undertake a good deal of research to get the detail of Glasgow and the art world right.

When it came to Sugar Money, research had a hand in steering the plot. These were real people, enslaved people, and I felt I owed it to them to stick closely to the facts. Having said that, there are great gaps in what is known about the true story behind the novel, with the result that I had a lot of inventing to do. With some of the people involved, all I had to go on was a list of slave names and it was from those names that I built their characters. For instance, I just knew that someone called Angelique Le Vieux had to be a force of nature. At other times, in terms of narrative, I had to piece together the plot by looking at the motivation of a character and analyzing what actually happened in real life e.g.: X happened and then Y happened – so why did the person involved make the decision to do Y? That’s often how the narrative grew. So, the facts often drove the fiction.

Sugar Money is a gripping book waiting to be turned into a period film. The descriptions are so vivid that it seems the action is happening in front of one’s eyes.

Jane Harris Sugar Money Faber & Faber, London, 2017, rpt 2018. Pb. pp. 452 Rs 499

*As I was writing this blog post news came in that US Attorney General Jeff Sessions cited Romans 13 from the Bible often used to defend slavery while defending his government’s policy of separating immigrant families.

15 June 2018