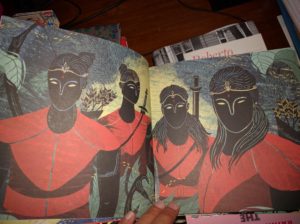

Manu Pillai’s “Rebel Sultans: The Deccan from Khilji to Shivaji”

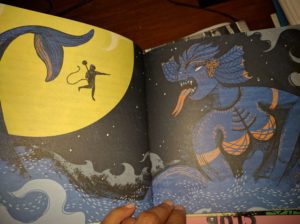

Award-winning writer Manu Pillai’s Rebel Sultans: The Deccan from Khilji to Shivaji makes the history of Deccan very accessible. It is a region of India that has been ruled by many dynasties from the north and south. It is also a a region that is strategically important and many vie for it such as the Vijayanagar kingdom and the Mughals. In Rebel Sultans, Manu Pillai narrates the story of the Deccan from the close of the thirteenth century to the dawn of the eighteenth; the Bahmanis, the Mughals and the Marathas including Shivaji. There are interesting titbits of information such as this one of Firoz Shah or of Ibrahim Adil Shah II or “habshi” Malik Ambar, an African slave who rose to power.

Award-winning writer Manu Pillai’s Rebel Sultans: The Deccan from Khilji to Shivaji makes the history of Deccan very accessible. It is a region of India that has been ruled by many dynasties from the north and south. It is also a a region that is strategically important and many vie for it such as the Vijayanagar kingdom and the Mughals. In Rebel Sultans, Manu Pillai narrates the story of the Deccan from the close of the thirteenth century to the dawn of the eighteenth; the Bahmanis, the Mughals and the Marathas including Shivaji. There are interesting titbits of information such as this one of Firoz Shah or of Ibrahim Adil Shah II or “habshi” Malik Ambar, an African slave who rose to power.

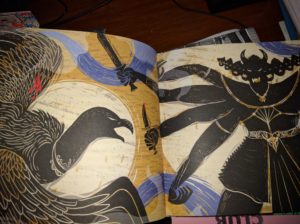

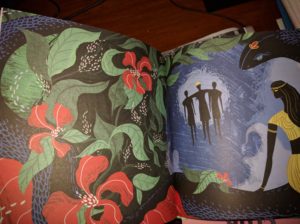

In an Economic Times article he wrote to coincide with the publication of his book, Manu Pillai says of Firoz Shah that he came to power because of a coup but was an interesting person. He was a polyglot who spoke everything from Turkish to Marathi, reading the Hebrew Bible and composing Persian poetry. Later in 1406, after war with Vijayanagar’s emperor, a princess of the Sangama dynasty was also given to Firoz Shah as a bride. But for her dowry, the sultan demanded not only the usual mountains of gold, gems and silver, but also as many as 2,000 cultural professionals from southern India. Scholars, musicians, dancers, and other persons of talent from a different cultural universe, arrived in the Bahmani Sultanate, combining with Persian poets and immigrant Sufis to exalt (and transform) its own notions of taste, art and culture. These were different worlds from which they emerged but together in a common space, they also found points of convergence.

Rebel Sultans is packed with information in this narrative history of the Deccan. As Manu Pillai told William Dalrymple in an interview that little narrative history about India exists as what is often lacking is a method to communicate that to a wider audience. Fortunately this is changing slowly. Manu Pillai adds, “My own effort has been to bridge that gap — to use the best of research, rigorously studied, and to convey it in a style and language that can appeal to a diverse readership. I think narrative history is here to stay, and if people can marry good research with elegant writing, we could really enrich ourselves.”

Offering a new perspective on the past is a critical component of nation building processes as well. This is not a new  concept. It was first seen practiced in medieval European communities evident in its literature and historical narratives they created such as Malory’s Morte d’Arthur. ( A story that adapted many of the Romance cycle stories to tell the story of a renowned king who created England as a nation.) In fact a question often discussed in recent times is whether a nation can have many versions of history. Increasingly connections between geographical regions, the environment and history are now beginning to be made. Eminent historian Romila Thapar says in The Past as Present “Historical perspectives are frequently perceived from the standpoint of the present.” It is particularly true when revisiting histories which are a representation of the past based on information put together by colonial scholarship. While unpacking the past as many historians do, they discover “that the past registers changes that could alter its representation. The past does not remain static.” In an interesting observation about the significance of regional history she says:

concept. It was first seen practiced in medieval European communities evident in its literature and historical narratives they created such as Malory’s Morte d’Arthur. ( A story that adapted many of the Romance cycle stories to tell the story of a renowned king who created England as a nation.) In fact a question often discussed in recent times is whether a nation can have many versions of history. Increasingly connections between geographical regions, the environment and history are now beginning to be made. Eminent historian Romila Thapar says in The Past as Present “Historical perspectives are frequently perceived from the standpoint of the present.” It is particularly true when revisiting histories which are a representation of the past based on information put together by colonial scholarship. While unpacking the past as many historians do, they discover “that the past registers changes that could alter its representation. The past does not remain static.” In an interesting observation about the significance of regional history she says:

The interest in regional history grew by degrees, assisted to some extent by the creation of linguistic states from the late 1950s, superseding the more arbitrary boundaries of the erstwhile provinces of British India. The newly created states came to be treated by historians as sub-national territorial units, but present-day boundaries do not necessarily hold for earlier times. Boundaries are an unstable index in historical studies. Ecologically defined frontier zones are more stable. The perspective of sub-continental history, conventionally viewed from the Ganga plain, has had to change with the evidence now coming from regional history. For example, the history of south India is much more prominent in histories of the subcontinent than it was fifty years ago. Regional histories form patterns that sometimes differ from each other and the variations have a historical base. Differences are not just diversities in regional styles. They are expressions of multiple cultural norms that cut across monolithic, uniform identities. This requires a reassessment of what went into making the identities that existed in the past.

In his fascinating account of the Deccan, Manu Pillai unpacks a lot of history to understand the regional history of an area that has always been strategically significant and continues to be in modern times. Combining storytelling with historical evidence is always a good idea for it keeps history alive in people’s consciousness but it is a fine line to tread between getting carried away in telling a juicy story and presenting facts as is. Nevertheless Rebel Sultans will be an important book for it straddles academia and popular writing. A crucial space to inhabit when there is an explosion of information available; but how to ensure its authenticity will always be tricky.

Rebel Sultans will be accessible to the lay reader as well as to the professional historian for a long time to come.

Manu S. Pillai Rebel Sultans: The Deccan from Khilji to Shivaji Juggernaut Books, Delhi, 2018. Hb. pp. 320 Rs. 599

17 June 2018