“‘Unsafe’ was a feeling he was familiar with.”

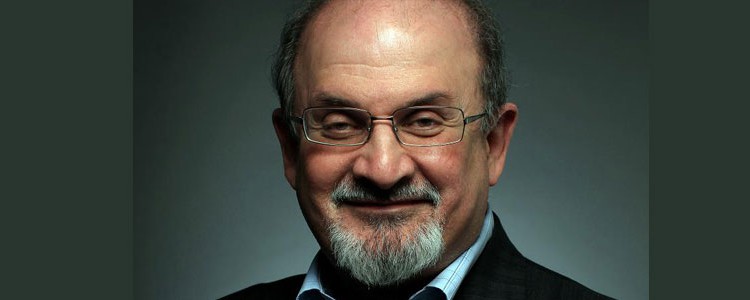

Salman Rushdie’s memoir Joseph Anton was released in 2012. Well before it was published it was being discussed–what will be said, what will not, will it live up to expectations etc. The title is borrowed from the names of two writers whom Rushdie admires, Joseph Conrad and Anton Chekhov. The nearly 600 pages are preoccupied with a decade of living under the fatwa, a death threat issued by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini of Iran ordering Muslims to kill Rushdie having written Satanic Verses. From the announcement of the news on 14 February 1989 till the threat perception was reduced to level four by Scotland Yard, Rushdie documents his complete bewilderment, growing frustration, simmering rage and absolutely disgust at the reactions of many who did not support him. He meticulously records his growing isolation from family and friends; the desperation at wanting to socialise but never being able to, at least not without prior planning with the police officers deputed to protect him; and then his growing rage at the hijacking of freedom of expression especially at the altar of religious zealots. He does not mask his distaste for his colleagues in the creative industry who fail to support him, including the “big unfriendly giant Roald Dahl”.

Interestingly he uses the third person technique to write. As if he is a dispassionate observer of what Joseph Anton experiences, though at times “Salman” does intrude and speaks, introspects and reflects. It is curious that many of the reviews ( a few are reproduced below) comment upon the technique recognise it to be a unique way of writing, but do not understand the import of it. Whereas if you read any written account by a woman of a trauma that she has experienced, when the moment comes to describe the actual event, she inevitably switches to the third person narrative. ( It is rare indeed for it to be ever written in the first person. And if it is, then it is usually a draft that has been worked upon extensively till it is worked out of the system of the victim.) In Joseph Anton Rushdie describes a period of his life that must have been fraught with anxiety for every second of the day and night. So it is not surprising that even though he had his diaries to refer to he opts to use a technique that makes the memory of living with terror 24×7 easier to write about. It is fascinating to see him use a writing technique that is normally not associated with men.

Joseph Anton is a detailed account of what happened in that frightful decade of Rushdie’s life, but also consists of references to his family and friends. It is a delightful balance of the personal and professional aspects of a very public figure. Graham Greene was amused that Rushdie had got into more trouble than Greene himself ever had! Whereas Gabriel Garcia Marquez never asked him about the fatwa. They had a straightforward conversation about writing and books, much to the relief of Rushdie. And of course the famous literary spat that John le Carre and Rushdie had in 1997. It was finally called off in November 2012 ( http://www.guardian.co.uk/theguardian/from-the-archive-blog/2012/nov/12/salman-rushdie-john-le-carre-archive-1997 and http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2012/nov/12/salman-rushdie-john-le-carre ). The ups and downs with the family, understanding his parents and their marriage and his utter and complete adoration for his two sons born eighteen years apart — Zafar and Milan– comes through very clearly. The passages on publishing, literary agents, sale of rights, publishing schedules makes one wonder whether the digital age revolution has really changed anything at all. The details, the arguments, the negotiations are the same, whether it was in the 1980s or now. There are moments when the editorial inputs should have been stronger since the text tends to get a little clunky and tedious, yet it reads well.

Years ago I recall attending a literary event where Salman Rushdie with Padma Lakshmi were also present. It was at the Oxford Bookstore, Statesman House, New Delhi. They were (I think) guests of William Dalrymple who was at the store to do a reading. For a long time I reflected upon that evening, but after reading Joseph Anton, a lot is explained especially the sheer joy of Rushdie at being able to live a normal life.

Whenever Rushdie writes non-fiction he does it extremely well. Those years of being “invisible” and yet not, being catapulted onto the front pages of the newspapers worldwide gave him the confidence to speak clearly and strongly. He says what he wants to say. One of the most recent examples being the speech he gave at the concluding dinner at the India Today Conclave, New Delhi held on 18 March 2012. ( http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tNzGgYvz92s). He insists that everyone should be allowed to speak without fear. He never really did, now he definitely does not, feel the need to mince words. I liked Joseph Anton.

30 May 2013

Salman Rushdie Joseph Anton: A Memoir Jonathan Cape, London, 2012. Hb. pp. 650 Rs 799

- Examples of reviews of the book, dwelling upon the third person technique

http://observer.com/2012/10/gone-underground-in-a-new-memoir-salman-rushdie-looks-bach-at-his-fatwa/ “The first thing readers will notice about this memoir is that the memoirist has written it in the third person. It is not a perspective often associated with self-awareness.”

http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2012/09/18/11-revelations-from-salman-rushdie-s-memoir-joseph-anton.html “…the book is written in the third person, as if a ‘biography’ of Rushdie/Anton…”

Pankaj Mishra in the Guardian (http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2012/sep/18/joseph-anton-salman-rushdie-review ) “In his memoir, where Rushdie bizarrely decides to write about himself, or “Joseph Anton”, his Conrad-and-Chekhov-inspired alias, in the third person, … .