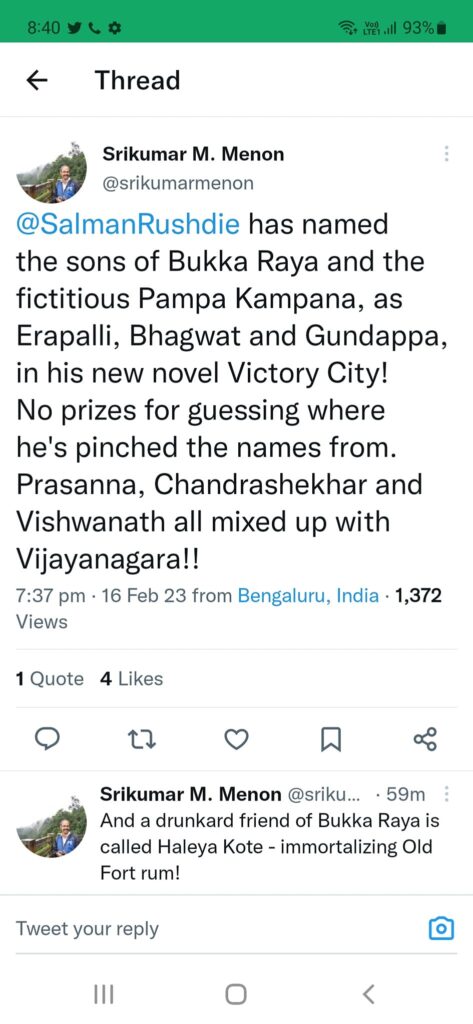

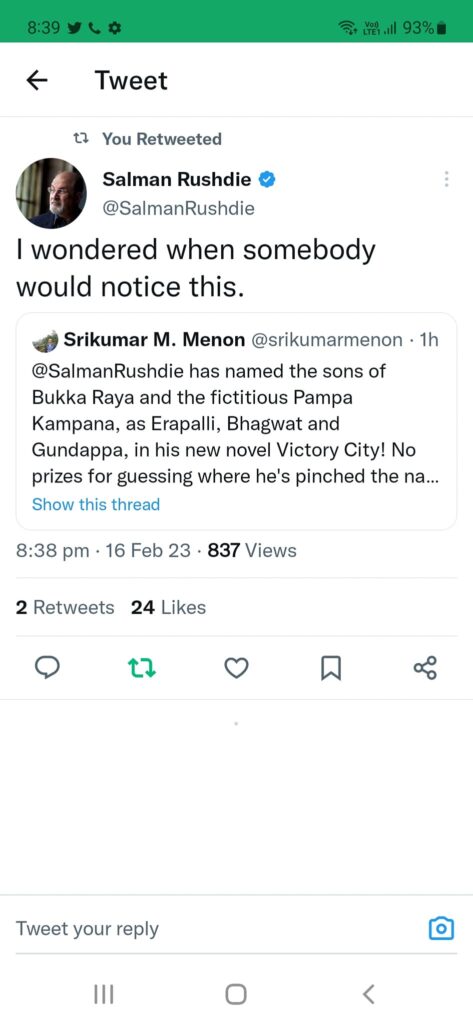

Salman Rushdie tweets on 16 Feb 2023

19 Feb 2023

19 Feb 2023

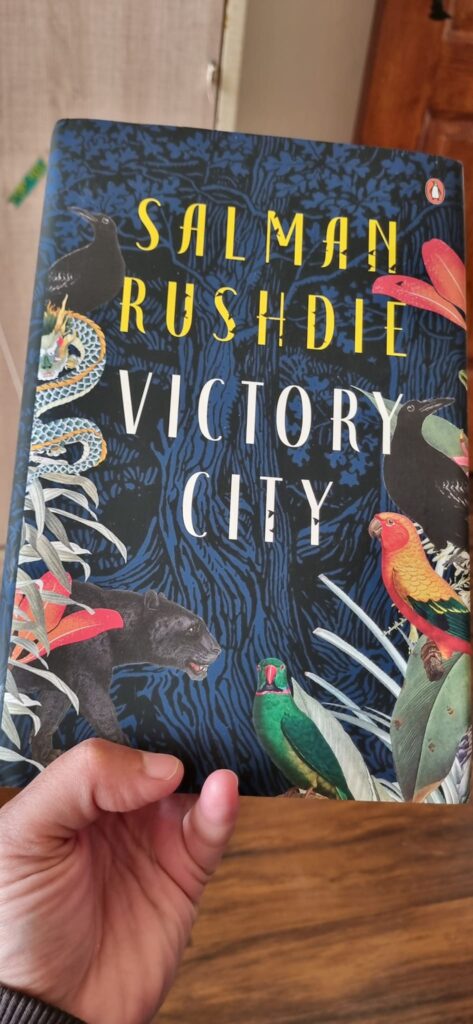

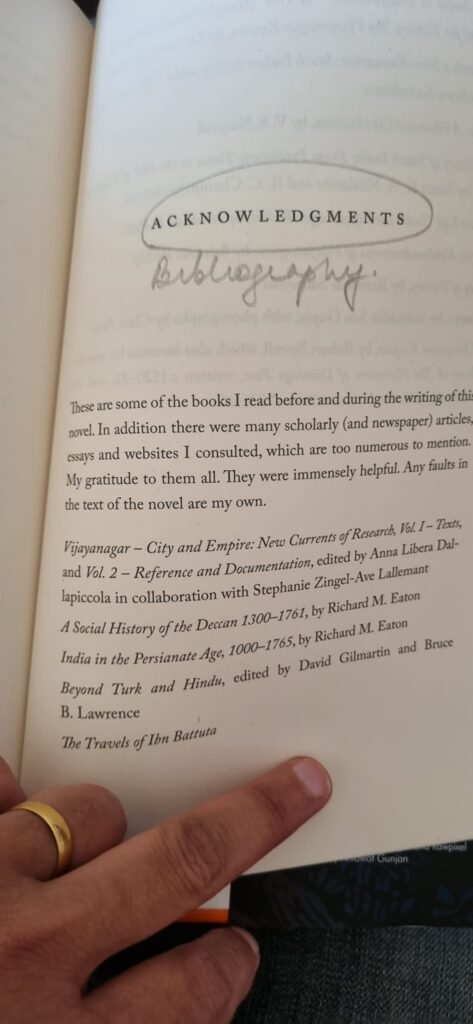

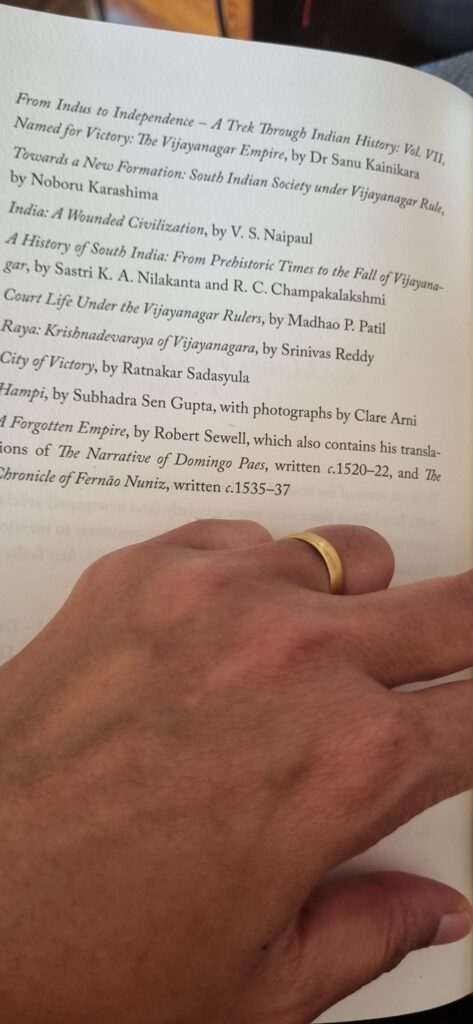

This is utterly fascinating. Without letting on about the story, the fact that the list of acknowledgments is actually a bibliography in Salman Rushdie’s Victory City, is just so perfect. Literally, for an eminent author like him, and within the immediate literary context of the novel.

Hopefully, the wonderful historian-cum-storyteller Subhadra Sen Gupta is seeing the due acknowledgements to her from wherever she is now.

Here is the link to David Remnick’s profile of Salman Rushdie, “The Defiance of Salman Rushdie”, published in the New Yorker, Feb 2023.

9 Feb 2022

On 3 January 2021, I wrote about the wonderful books expected to be published in 2021. Here are the original links in the Asian Age and Deccan Chronicle. Given below is the longer version of the article.

****

The Covid-19 pandemic has disrupted innumerable sectors – publishing is no exception. One of the major fallouts has been the front lists where commissioning editors are circumspect about whom to commission and what subjects to explore; it is not said explicitly but it is apparent while scanning 2021 book catalogues that there has been a shift. Tried and tested subjects such as politics, memoir/biographies and narrative non-fiction exist but there is a definite presence of essayists and nature writing. The top 1% of successful literary and commercial fiction authors — internationally and locally—are back with new books. Interestingly there is a large variety of debut authors, from newcomers to well-known nonfiction writers becoming novelists such as Ira Mukhoty Jayal, Krupa Ge and Tavleen Singh. Historical fiction is a robust category with trilogies and quartets being announced by writers like Jerry Pinto and Madhulika Liddle. Surprisingly celebrity publishing and Mind, Body Spirit (MBS) that are constant sellers are not as prominent as they were in the recent past.

During the pandemic, it is a wise decision by publishers to ensure that successful authors constitute a chunk of their front lists. Hence, in non-fiction, there is Shashi Tharoor’s Pride, Prejudice & Punditry: The Essential Shashi Tharoor consists of essays and fiction; Salman Rushdie’s Languages of Truth has newly collected, revised and expanded non-fiction from the past two decades, many of which have never been published before; Ruskin Bond’s It’s a Wonderful Life: Roads to Happiness that calls for small joys to be found in everyday living even in times of extreme stress; A Functioning Anarchy (Eds. Srinath Raghavan and Nandini Sundar) a collection of essays by world-renowned historians, lawyers, scientists and journalists sparked by Ramachandra Guha’s work; Nayantara Sahgal’s The Unmaking of India: Articles and Speeches & Encounter with Kiran contains articles, talks, essays that discuss the “unmaking” of India, where freedom, liberty and equality are replaced by religious bigotry, communal politics, a ‘’tame’’ media and all the accompanying dangers of majoritarian rule and Eric Hobsbawm’s On Nationalism that is considered to be an insightful and enlightening collection of the historian’s writing on the subject of nationalism.

Non-fiction sells consistently especially on politics, history, business, self-help, memoirs/biographies etc. Some of the exciting titles scheduled are historian Upinder Singh’s Ancient India: Culture of Contradictions ; Amit Varma’s podcasts converted into four books, collectively known as The Seen and the Unseen; Amitav Ghosh’s The Nutmeg’s Curse: A Parable for a Planet is about conquest and exploitation and geopolitical hierarchy; Manu Pillai’s The World of Raja Ravi Varma: Princes and Patrons describes the portraits of the Maharajahs stood up to the Raj and developed visions of modernity that were deeply Indian in nature, and women who defied norms as well as colonial expectations; City of Gated Walls: The Map of Shahajahanabad by Swapna Liddle is a reproduction of that map created in Bahadur Shah Zafar’s time by a mapmaker, working in 1846, who painstakingly depicted important buildings, streets, and landmarks, providing a wealth of information about the city as it had evolved up to that time. In Search of the Divine: Living Practices of Sufism in India by Rana Safvi, is a unique treatise on the core of Sufi beliefs. Some others that are eagerly awaited include 1946: The Indian Naval Uprising that Shook the Empire by Pramod Kapoor; The Gujaratis: A Portrait of a Community by Salil Tripathi; Congress Radio by Usha Thakkar about the establishment of the underground radio by Usha Mehta during the Quit India Movement; Aparna Vaidik’s Revolutionaries on Trial: Sedition, Betrayal, and Martyrdom uses a variety of sources to reconstruct a dramatic period in India’s struggle for Independence; and Angellica Aribam and Akash Satyawali’s The Fifteen: The Women Who Shaped the Constitution of India. Rupa Gupta and Gautam Gupta’s Lifting the Veil from India’s Past is about the Archaeological Survey of India. In Language of Remembering: Generational Memories of the Partition, Aanchal Malhotra shifts attention to the post-memory generation – how the generations that have not witnessed Partition engage with its history. Yashaswini Chandra The Tale of the Horse: A History of India on Horseback is a tale of migration and permanent intermingling whereas Winged Stallions and Wicked Mares: The Horse in Indian Myth and History by Wendy Doniger examines the horse’s significance throughout Indian history and culture even though the animal is not indigenous to India. Voices from the Lost Horizon is a collection of a number of folk tales and songs of the Great Andamanese that represent the first-ever collection rendered to Prof. Anvita Abbi and her team by the Great Andamanese people in local settings. The compilation comes with audio and video recordings of the stories and songs to retain the originality and orality of the narratives. In Fellowship of Rivals by Manjit Kumar that tells the story of the first great Scientific Revolution, and how a small group of individuals – including Isaac Newton, Robert Hooke and Christopher Wren – produced an explosion of knowledge unrivalled in the history of western civilisation. Pranay Lal’s Virus is a deep dive into its origin and evolution and his The Cretaceous is meant for younger readers. Anjana Chattopadhyay discusses Women Scientists in India: Lives, Struggles and Achievements.

Militant Piety and Lines of Control: The Lethal Literature of the Lashkar-e-Taiba edited by C. Christine Fair and translated by Safina Ustaad is the first scholarly effort to curate a sample of LeT’s Urdu-language publications and then translate them into English for the scholarly community studying this group and related organizations. The Muslim Problem by Tawseef Khan gets to the heart of Islamophobia and is a compelling mix of journalistic investigation, historical analysis and memoir, full of research and interviews. Tawseef Khan is a solicitor specialising in Immigration and Asylum Law and a human rights activist. In Project 39 are deeply personal stories that emerged from interviews conducted with death-row prisoners and their families. These were collected by Jahnavi Mishra and Project 39A, a research and litigation centre based out of National Law University, Delhi. is awaited as is India’s First Dictatorship: The Emergency, 1975-77 by Christophe Jaffrelot and Pratinav Anil that draws upon a trove of new sources. From the bestselling military historian, Shiv Kunal Verma’s 1965: A Western Sunrise is the definitive account of the 1965 war between India and Pakistan. Meanwhile Samira Shackle’s debut Karachi Vice is considered to be a fast-paced journey around Karachi in the company of those who know the city inside out. Some others that are expected: When the Mask Came off: A People’s History of Cruelty and Compassion in Times of Covid19 Lockdown, edited by Harsh Mander, Natasha Badhwar and Anirban Bhattacharya; Jana Gana Mana by musician-activist T.M. Krishna who through the idea of ‘national symbols’, examines the idea of citizenship and belonging, while also investigating and problematising the symbol itself. Graphic narratives such as Azaadi: A Biography of Bhagat Singh by Ikroop Sandhu; Shaheen Bagh: A Graphic Book by Ita Mehrotra and Incantations over Water by Sharanya Manivannan.

Nature writing is proving to be a well-defined genre as well. The titles to look out for are The Bera Bond which is about Sundeep Bhutoria’s startling discovery of a little-known leopard colony in the forests of Rajasthan where the big cats live harmoniously with humans. The Braided River: A Journey Along the Brahmaputra, journalist Samrat Choudhury sets out to follow the river’s braided course from the edge of Tibet where it enters India down to where it meets the Ganga at a spot marked by the biggest red-light district in Bangladesh. Award-winning wildlife conservationistNeha Sinha’s Wild and Wilful is about fifteen iconic Indian species in need of conservation and heart. Earth’s Incredible Oceans by Dorling Kindersley is a must-have encyclopaedia. Waiting for Turtles by Pankaj Sekhsaria, illustrated by Vipin Sketchplore is a gorgeous picture book sensitising children to the urgency to save turtles. Scientist-cum-author Sukanya Datta’s Animal Architects is about the homes that animals build and are in themselves architectural wonders. The Heartbeat of Trees by Peter Wollehben (translated by Jane Billinghurst), reveals the profound interactions humans can have with nature, exploring the language of the forest and the consciousness of plants. Worryingly climate change can wreak havoc to these ecosystems. Hence the relevance of environmental activist Vandana Shiva and Shreya Jani Slow Living: What You Can Do About Climate Change. Bill Gates too has a forthcoming book on How to Avoid a Climate Disaster.

Memoirs have always proven to be popular. Some of the prominent ones are MK Gandhi’s Restless as Mercury: My Life as a Young Man; the celebrated Hindi writer Swadesh Deepak I Haven’t Seen Mandu, translated by Jerry Pinto is a most revealing and powerful first-person accounts of mental illness; Feisal Alkazi’s Enter Stage Right: The Alkazi / Padamsee Family Memoir; Gulzar’s Actually… I Met Them: A Memoir, Vir Sanghvi by journalist Vir Sanghvi; Bollywood actors Neena Gupta, Deepti Naval and Priyanka Chopra Jonas have written Sach Kahun Toh, A Country Called Childhood: A Memoir and Unfinished: A Memoir respectively but the big one will be Hollywood actress Sharon Stone’s The Beauty of Living Twice; screenwriter Nikesh Shukla’s Brown Baby explores themes of racism, feminism, parenting and our shifting ideas of home; publisher Ritu Menon’s ADDRESS BOOK: A Publishing Memoir in the Time of COVID; Kobad Ghandy’s Fractured Freedom: A Prison Memoir gives an insight into his decade-long journey of arrests and time in prisons across India; Dead Men Tell Tales by forensics expert Dr B. Umadathan (translated from Malayalam by Priya K. Nair) is the riveting memoir of Sherlock Holmes of Kerala. Former cricketer and commentator and current head coach of the Indian national cricket team Ravi Shastri’s memoir written with Ayaz Memon.

Biographies whether authoritative or not are hugely popular such as Yasser Usman’s Guru Dutt: An Unfinished Story; Kaveree Bamzai’s The Three Khans about Aamir Khan, Salman Khan and Shah Rukh Khan; Gautam Chintamani Vinod Khanna: A Biography; Zohra! – A Biography in Four Acts by Ritu Menon about thespian Zohra Sehgal; Francis Wilson’s biography of DH Lawrence called Burning Man; Adi Prakash’s Umar Khalid: Beyond the Anti-national is the story of Umar Khalid is the story of media fairness and it is the story of student politics and of growing up Muslim in India. Also expected are the Hindi writer and the first real standard-bearer of the Nayi Kahani movement Nirmal Verma: A Biography by Vineet Gill and The Master: The Brilliant Career of Roger Federer by Christopher Clarey.

Business books are another category of nonfiction books that sell perennially. Investigative journalist Josy Joseph’s The Business of Terror explores the militancy theatre as a flourishing, multi-faceted business enterprise in India where most of its actors are beneficiaries of it. Technology journalist Jayadevan P.K. writes about Xiaomi: How a Start-up Disrupted the Market and Created a Cult Following that in less than a decade, has gone from being a Chinese start-up to a global player in the smartphone market. Munaf Kapadia with Zahabia Rajkotwala writes in How I Quit Google to Sell Samosas: Adventures with the Bohri Kitchen how he had grown a weekend pop-up at his Cuffe Parade home—The Bohri Kitchen—into an F&B start-up with a Rs 4 crore turnover, and was catering to Bombay’s biggest celebrities. Liftoff: Elon Musk and the Desperate Early Days That Launched by Eric Berger is the dramatic inside story of the first four historic flights that launched SpaceX—and Elon Musk—from a shaky startup into the world’s leading edge rocket company. Tata: The Global Corporation That Built Indian Capitalism by Mircea Raianu is a eye-opening portrait of global capitalism spanning 150 years, told through the history of the Tata corporation. Forgotten Brands: Fresh Marketing Lessons by Ramya Ramamurthy is about colonial Indian brands (both home-grown and foreign) were produced, distributed and marketed between 1847 and 1947. Finally, House of Pain by Patrick Radden Keefe is the story of the Sackler Dynasty, Purdue Pharma, and their involvement in the opiod crisis that has created millions of addicts, even as it generated billions of dollars in profit.

Another popular nonfiction category are cookery books. So, it is no surprise then that practically every publisher has at least one book in the pipeline. Beginning with Sunita Kohli who has collected recipes from celebrities in From the Tables of My Friends; Winner of Nobel Prize in Economics (2019) Abhijit Banerjee’s cookbook; History Dishtory: Adventures and Recipes from the Past by Ranjini Rao and Ruchira Ramanujam and Indian Street food by Rocky Singh and Mayur Sharma. Chitrita Banerji’s A Taste of My Life is both the story of life as an immigrant food writer as well as a story of immigration, belonging, nostalgia, and history, through the lens of food. Rasa: The Story of India in 100 dishes by Shubhra Chatterji is a culinary history of India and the intersection of culture and cuisine told in the most enthralling stories behind a hundred dishes.

Across the board, literary fiction stalwarts return in 2021 with promising new stories. Chitra Bannerjee Divakurni’s novel The Last Queen is an exquisite love story about Maharaja Ranjit’s Singh’s last queen, a commoner, Jindan Kaur; Amitav Ghosh’s Jungle Nama: A Story of the Sundarban, a verse adaptation of the timeless legend of Bon Bibi and Dokkhin Rai that also evokes the wonder of the Sundarban through its poetry, accompanied by stunning artwork by the renowned artist Salman Toor. Asoca by I. Allan Sealy is an imagined memoir of Ashoka The Great; Hussain S. Zaidi’s The Black Orphan centres on Asiya, Osama Bin Laden’s protégé and foster daughter; Anuja Chauhan returns with a grisly titled Club You to Death as does Padma Shri Temsula Ao with six short stories in The Tombstone in My Garden; writers of young adult fiction like Deepa Agarwal’s Kashmir! Kashmir! and Paro Anand’s short stories Unmasked based on the challenges faced by migrants during the lockdown. Annie Zaidi’s novel, One of Them is about people who live on the margins of a big city, and Amitava Kumar A Time Outside This Time is about fake news, memory, and how truth gives way to fiction. The Loves of Yuri by Jerry Pinto is a funny, heart breaking, unforgettable novel about friendship and first loves and the great city of Bombay. Set in the 1980s, this is the first in a trilogy of novels that trace the emotional and intellectual journey of the protagonist, Yuri, from early adolescence to late youth. Nobel Prize winnersKazuo Ishiguro and Orhan Pamuk’s novels Klara And The Sun and Nights of Plague, respectively are hugely anticipated as is the mind bending new collection of short stories First Person Singular by Haruki Murakami. Pulitzer Prize-winners Jhumpa Lahiri, Viet Thanh Nguyen and Colson Whitehead’s novels are called Whereabouts, The Committed and Harlem Shuffle. This is the first novel Lahiri has written in Italian and translated into English. Tahmima Anam’s, already much-talked-about, The Start-Up Wife is considered gripping, witty and razor-sharp, a blistering novel about dreaming big, speaking up and fighting to be where you belong. Second-time novelists who had glittering starts to their literary careers like Anuk Arudpragasam, Sunjeev Sahota and Elizabeth Macneal return with In Search of the Distance, China Room, and Carnival of Wonder respectively.

The debut writers making their mark are Maithreyi Kapoor Sylvia’s Distant Avuncular Ends by experimenting with the form of a novel. Poet Kynpham Sing Nongkynrih’s novel Funeral Nights, where the absurd and the sublime all freely mix,is a history of the Khasis. Krupa Ge’s One Hundred Autumns is set in an era of strict Brahmanical orthodoxy and social mores that sought to bind all women into submission and against the backdrop of the Dravidian movement. Ira Mukhoty Jayal’s Song of Draupadi is a vivid and imaginative novel revolving around the epic figure of Draupadi. Raza Mir’s Murder at the Mushaira: A Novel is a cracking murder mystery & literary novel. Filmmaker Devashish Makhija’s Oonga, a powerful novel that transitions from a film and sits deep in the clash between adivasis, naxalites, the CRPF and a rapacious mining company; Simran Dhir’s Best Intentions, centred on two families in Delhi; Fahad Shah’s The Unnamed, a searing novel set in Kashmir; and Bollywood insider Mushtaq Sheikh’s sizzling Bollywood Biwis. Some of the others to watch out for are Rucha Chitrodia It’s also about Mynah, Zakiya Dalila Harris’s The Other Black Girl, Rijula Das’s A Death in Shonagachhi,journalists Anindita Ghose’s The Illuminated: A Novel and Tavleen Singh’s Everything Breaks.

Historical fiction is a well-defined niche with The Grand Anicut by Veena Muthuraman, set in Southern India, first century, with the Pandyas conquered, the Cheras all but vanquished, and the attention of the king of the north fixed on other lands, Tamilakam flourishes under Chola rule. The first book of Madhulika Liddle’s Delhi quartet — The Garden of Heaven is planned. It is a story playing out against a backdrop of Delhi, stretching from the end of the twelfth century (when Delhi first came under the rule of Sultans) till 1947. Shubendra’s Sultan: The Legend of Hyder Ali, set in the eighteenth century, is the astonishing tale of an ordinary boy from Mysore who became one of the greatest rulers of India. Tarana Khan’s The Begum and the Dastan although set in the late nineteenth century, in the fictional town of Sherpur, is a work based on real events. A despotic Nawab abducts a married woman, Feroza, and marries her against her wishes. Feroza must now negotiate her new life in the zenana with the other wives and concubines of the Nawab. Digonta Bordoloi’s Second World War Sandwich is a thrilling action-packed novel set in Nagaland during the Second World War, when the Nagas resisted the incursion of the Japanese troops into Northeast India. The Paris Library by Janet Skeslien Charles is inspired by the true story of the librarians who risked their lives during the Nazis’ war on words. Melody Razak’s Moth is a heart-rending story of a Brahmin family living in 1940s Delhi during India’s Independence and subsequent Partition. A Net for Small Fishes by Lucy Jago, explores the twisting corridors of power and with the friendship of two women at its heart, it is an exhilarating dive into the pitch-dark waters of the Jacobean court.

Some of the noteworthy translations expected are Ambai’s short stories A Red-Necked Green Bird, translated from Tamil by GJV Prasad; the Bengali classic, Manada Devi’s An Educated Woman in Prostitution: A Memoir of Lust, Exploitation, Deceit (Calcutta,1929), translated by Arunava Sinha; Amrita Pritam’s Pinjar or The Cage, translated from Punjabi by Rita Banerji, was written in 1950, and was the very first to approach Partition and its aftermath through the eyes of a woman; Kaajal Oza Vaidya’s Krishnayan, gives glimpses into Krishna’s last moments on earth, translated from Gujarati by Subha Pande and The Last Gathering: A vivid portrait of life in the Red Fort by Munshi Faizuddin, translated by Ather Farooqui. It was first published in 1885, Bazm-i Aakhir, or The Last Assembly and is a rich and lively account of life in the royal court of the last Mughal emperor in Red Fort, Bahadur Shah Zafar.

So many frills, thrills and spills! Reading good literature will help survive this pandemic.

3 Jan 2021

The Booker Prize is to be announced on Monday, 14 October 2019. This time it consists of very well established writers and previous Booker winners like Margaret Atwood and Salman Rushdie. The other writers shortlisted include Elif Shafak, Chigozie Obioma, Lucy Ellmann and Bernardine Evaristo. Every single title shortlisted is unique and that is exactly the purpose of a shortlist — to highlight the variety of writing, experimentation in literary forms and the author’s ability to tell a fresh new story.

Quichotte by Salman Rushdie is a modern enactment of Cervantes Don Quixote and involves a salesman of Indian origin, Ismail, who travels across America on a quest — in search of his beloved, a TV show host. It is at one level a bizarre retelling of the popular story with big dollops of magic realism also thrown in. But most importantly it is the commentary offered on the global rise of despots, notion of dual identities, migrations, what it means to be a refugee in modern times, status of women, patriarchal ways of functionining, sexual harassment etc. It is like a broad sweep of events set in three nations — USA, UK and India. At the same time it is a commentary that is very relevant to the socio-political turmoil evident globally. These are also the three countries that Rushdie has lived in and migrated to. So Quichotte in many ways is a triumphant storytelling but it is also a sharp commentary on contemporary events that are taking a horrific turn. In many ways this is a sad reminder for someone like Rushdie, a Midnight’s Child, born soon after India gained independence from the British in 1947 and wrote about it in his Booker winner and Booker of Bookers The Midnight’s Children. He has witnessed modern history for more than seven decades and to see history more or less come full circle with the rise of fascism and blatant acts of genocide, construction of concentration camps in the name of detention centres for migrants is a more than unpleasant. It requires a storyteller of his stature who has himself lived under the very real threat of death while the fatwa issued against him for writing The Satanic Verses existed, to write confidently and offer his commentary on modern times. If the garb of magic realism, a quest and relying upon many literary references that at times allow Rushdie to offer his thoughts while making Quichotte seem disjointed, well, ce’st le vie — it is a reflection of our reality and needs to be articulated. Read this extract from the novel. Also listen to this fascinating podcast on the Intelligence Squared website where Salman Rushdie spoke to BBC journalist Razia Iqbal in front of a live audience in London on 29 August 2019.

Elif Shafak’s 10 Minutes 38 Seconds is a reference to the time the brain waves continue to be sent after a person has been declared clinically dead. This is the duration during which the novel’s protagonist, a prostitute called Tequila Leila, who has been killed and whose body has been placed in a sil, reflects upon her life and her friendships. It is a stunning book for its immediate preoccupation with refugees as epitomised by the small circle of friends of the narrator. It is also a story that touches upon gender issues, patriarchy, censorship, rise of fascist despots, freedom of expression, marginalised groups, sexual freedom etc. While it is a novel that raises many issues, it is unlike Quichotte, restricted to Turkey and its immediate vicinity. In an interview to the Indian Express, Shafak said, “The novel is one of our last democratic spaces“.

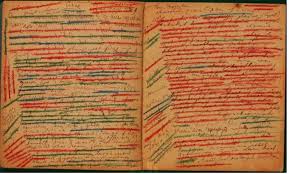

Lucy Ellmann’s Ducks, Newburyport is described as a one-sentence, 1000-page novel, which seems daunting to read, but it is the interior monologue of a woman. A narrator who merges her thoughts as most women do while contending with their daily mental load of managing responsibilities and offering commentaries upon the world around them. She flits between her immediate preoccupations with general reflections upon global politics, especially Trump. While reading the novel there are moments that one punches a fist in the air to say, “Yes! Ellmann got this right about women and their reflections.” Then there are other moments where one wishes that like James Joyce’s Ulysses manuscript written in colour-coded crayons, Lucy Ellmann too had figured a way of colour coding her novel by making the perceptive observations of a woman being highlighted for at times the meanderings into political landscapes and beyond can be a tad tedious. Lucy Ellmann’s writing style in this novel has often been compared to James Joyce by critics for whom the author had a fantastic reply in an interview she gave to The Washington Post:

Thrilled. But again, to me the connection seems remote. Many reviews have mentioned that my father was a Joyce scholar. Actually, my sister’s one too. But . . . I’m not! My father [ Richard Ellmann] did talk a lot about Joyce when I was growing up, when my mother didn’t put her foot down. But mostly, I tuned it out. I regret that now — especially when people come to me with their Joyce questions! Still, I think it’s weird for reviewers to bring up what my father did for a living. How often is the parentage of male novelists in their 60s mentioned?

Bernardine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other is a “novel” about 12 black women characters, most of them British. As an example of literary experimentation in terms of form, using blank verse as prose, to tell loosely interconnected, intergenerational, stories is fascinating. There is a rhythm that is mesmerising and lends sections of this novel to performance poetry. These are voices that suddenly make apparent the distinctions that exist amongst individuals in that “broad” spectrum of “black British women”. There are many instances in the book that make the women across generations offer their opinions about living in a patriarchal society, the position of women and the challenges it offers on a regular basis. Many of these questions are often raised and discussed even by feminists and many other ordinary women who do not necessarily wish to be labelled as feminists. The fact remains these are issues linking women across the world. Yet while the author’s heart is in the right place of creating this landscape, too much energy seems to have been invested in crafting the form rather than ensuring that the women’s conversations are at par with the magnificent form. At times, their observations sound too thin or as the Guardian review puts it aptly, “naive”. This mismatch in quality of craftsmanship and getting the tenor right of the women character’s preoccupations was not to be expected in such a talented writer. Evaristo is widely tipped to be one of the favourite of bookies and critics, like John Self in The Irish Times, in tomorrow’s announcement of the Booker Prize.

The only other writer on this year’s shortlist, apart from Rushdie, to have won the Booker Prize is Margaret Atwood with The Testaments. It is a sequel to her iconic book The Handmaid’s Tale which went through an immense revival achieving almost cult-like status in the wake of the #MeToo movement. It led to a TV adaptation where Atwood had a cameo role too. The red and white dress rapidly became a symbol of resistance in many a young woman’s mind. Atwood wrote The Testaments while the buzz around The Handmaid’s Tale was rife. It is undoubtedly a smoooooooooooth read and is justifiably so the “dazzling follow-up” to The Handmaid’s Tale as affirmed by Anne Enright in her review in The Guardian. Nothing less is to be expected from Margaret Atwood, the High Priestess of modern sisterhood, as she so marvellously creates this story even with its painful moments. It is a story that can be read as a standalone or in quick succession after The Handmaid’s Tale but the skill of Atwood’s storytelling comes to the fore in this novel. It is also probably easier to read, stronger in the punches it delivers and richer for its details, given that it is very much a product of modern times where many debates regarding women, their rights and freedoms within a patriarchal social structure are being questioned. The audience is now receptive to such tales. Hence it is no surprise that bookies are tipping this to be the favourite to win tomorrow’s Booker Prize.

Chigozie Obioma’s An Orchestra of Minorities is a retelling of Homer’s Odyssey in the form of Igbo storytelling. It is a kind of storytelling associated mostly with male storytellers. It merges many well known traditions of storytelling and is mostly anecdotal, relying a lot on folklore elements. It is a form that was used by Chinua Achebe in Things Fall Apart too. Obioma has been referred to in a New York Times article as the “heir to Chinua Achebe”. Nonso, a chicken farmer, is the protagonist in An Orchestra of Minorities who travels out of Nigeria and gets involved in many adventures including becoming the victim of a scam. It can get a little convoluted as presumably this Igbo art form is mostly meant for oral performances and not meant to be read as the printed word, a form that exerts its own set of rules and demands upon the reader — most noticeably being that of making limited allowances for digressions and purple prose. This constant tussle between the two forms of storytelling — Igbo and the English literary tradition of the novel— makes for a challenging read with only flashes of brilliance. Perhaps Obioma who has been most fortunate in having both his novels shortlisted for the Booker Prize will win this prestigious literary accolade with his third novel and not succumb to being “three times bridesmaid never bride”.

Literary shortlists serve many purposes. Most noticeably of showcasing the variety of literature available in that particular year of the prize announcement. These shortlists are increasingly becoming relevant to the socio-political events that seem to influence writing and reading patterns too. Within this context, the 2019 Booker shortlist is a formidable gathering of experienced writers. Everyone, even the most seasoned of writers, likes a win and the value of this prize is £50,000. Irrespective of how the bookies are placing the writers for tomorrow’s win, it will in all likelihood be a close call between Rushdie and Shafak. If Evaristo wins, it will only be because of the jury taking into consideration hyper-local factors of being a black woman writer in UK particularly during the Brexit phase. It would be perfect if Rushdie wins this prize once more, making it a hat trick for him at the Booker. He deserves to win for his literary fiction such as The Midnight’s Children and now Quichotte have not only documented critical moments in modern history but these novels are timely and relevant for the wisdom they impart. The characters in Quichotte are migrants like Rushdie and many others, “the broken people …are the best mirrors of our times, shining shards that reflect the truth“. Quichotte offers much more than just looking at a narrow canvas of one topic or one region but broadens the horizons to highlight many of the issues gripping the world are not bound to a nation state but are spread like a rash globally. What is even more horrific is that Rushdie has in his lifetime of three score years and ten witnessed crimes against humanity that one thought were rid off but seem to have returned with despicable vengeance. Quichotte is a triumph of literary craftsmanship as Rushdie is writing about these moments in history that he has witnessed while maintaining a firm grip on imbibing and merging many forms of literary traditions and storytelling to formulate a new one. There are far too innumerable to list in this round up. Suffice to say that if any novel in the shortlist deserves to win, it is Quichotte.

13 October 2019

Quichotte is a retelling of Cervantes Don Quixote. In this modern version a salesman of Indian origin, Ismail, travels across America on a quest in search of his beloved, a TV talk show host, Salma. Ismail is joined on his journey by his son. This is a mix of every kind of literary tradition — such as a play on the unreliable narrator of Moby Dick, “Call me Ishmael” — along with the anxiety of contemporary life — growth of fascism in global politics, migration, refugees, disintegration of families etc. It is a novel meant to be relished slowly as it is packed with wise observations apart from plain good storytelling. The following is a an extract from the novel that is impossible to forget:

An interjection, kind reader, if you’ll allow one: It may be argued that stories should not sprawl in this way, that they should be grounded in one place or the other, put down roots in the other or the one and flower in that singular soil; yet so many of today’s stories are and must be of this plural, sprawling kind, because a kind of nuclear fission has taken place in human lives and relations, families have been divided, millions upon millions of us have traveled to the four corners of the (admittedly spherical, and therefore cornerless) globe, whether by necessity or choice. Such broken families may be our best available lenses through which to view this broken world. And inside the broken families are broken people, broken by loss, poverty, maltreatment, failure, age, sickness, pain, and hatred, yet trying in spite of it all to cling to hope and love, and these broken people — we, the broken people! — may be the best mirrors of our times, shining shards that reflect the truth, wherever we travel, wherever we land, wherever we remain. For we migrants have become like seed-spores, carried through the air, and lo, the breeze blows us where it will, until we lodge in alien soil, where very often — as for example now in this England with its wild nostalgia for an imaginary golden age when all attitudes were Anglo-Saxon and all English skins were white — we are made to feel unwelcome, no matter how beautiful the fruit hanging from the branches of the orchards of fruit trees that we grow into and become.

From 11-13 February 2018 the 32nd International Publishers  Association (IPA) Congress was held at Taj Palace Hotel, New Delhi. The International Publishers Association (IPA) is the world’s largest federation of national, regional and specialist publishers’ associations. Its membership comprises 70 organisations from 60 countries in Africa, Asia, Australasia, Europe and the Americas. The congress was organised in Delhi along with the collaboration of the Federation of Indian Publishers ( FIP).

Association (IPA) Congress was held at Taj Palace Hotel, New Delhi. The International Publishers Association (IPA) is the world’s largest federation of national, regional and specialist publishers’ associations. Its membership comprises 70 organisations from 60 countries in Africa, Asia, Australasia, Europe and the Americas. The congress was organised in Delhi along with the collaboration of the Federation of Indian Publishers ( FIP).

It was a wonderful congress with multiple panel discussions that fortunately ran in succession rather than in parallel and many fascinating conversations were to be had on the sidelines. It was a phenomenal gathering of publishers from around the world. The full programme can be accessed here.

Day two the discussions continued as energetically as before. The highlights of the events on this day were the panel discussion on “The threat of self-censorship in publishing”. It was chaired by Kristenn Einarsson, CEO Norwegian Publishers Association; Chair, IPA Freedom to Publish Committee and the panelists were Trasvin Jittidecharak, Silkworm Books, Thailand and Jürgen Boos, President and CEO, Frankfurt Book Fair, Germany.

The Keynote speech was delivered by Norwegian publisher William Nygaard. On 11 Oct 1993 he was shot three times in the back outside his home. Although the crime was never resolved it is widely believed that this was linked to the fatwa William Nygaard received for publishing Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses. Both before and after the attack he has been a great defender of the freedom to publish and of free speech. His speech begins at 2:49:41 in the YouTube link given below:

Kristenn Einarsson during the course of conversation remarked that through libel laws economic sanctions are being imposed so allowing not necessarily governments but also people in power to really hit you economically if you publish something they don’t like or go to court with. So just a threat of that is hindering publishing.” Juergen Boos confirmed that the perception of self-censorship is on the rise particularly with the more and more populist governments being elected to power. At 3:32:12 Kristenn Einarsson remarks that the panel should have included an Indian publisher who could not make it and then opened the discussion to the floor except that once again no Indian stood up instead Edward Nawotka, Bookselling and International News Editor, Publishers Weekly spoke. He can be heard speaking off camera. ( Another equally telling observation is that while composing this blog post I discovered that Amazon India does not sell Rushdie’s Satanic Verses despite selling all his other books! )

Later in the day the 2018 IPA Prix Voltaire award ceremony was held. The award was given to Chinese-born Swedish scholar Gui Minhai who is a prolific writer often commenting on Chinese politics and political figures. He is one of the three shareholders of Causeway Bay Books in Hongkong. He went missing in Thailand in late 2015. It was received on his behalf by his daughter Angela Gui. “I think that my father’s version of optimism is perhaps precisely the kind that Voltaire describes. It’s an optimism that in the face of unimaginable cruelty still believes in change. And it’s an optimism that isn’t crushed by lies, force and humiliation.”

Bangladeshi Publisher Faisal Arefin Dipan was given a posthumous Special Award. He was brutally hacked to death inside his office at the hands of suspected religious extremists for his association with secular science writer Avijit Roy and other freethinking, secular and atheist writers on 30 October 2015. His widow, Razia Rahman Jolly, told the audience, “We have sacrificed our sunshine. We are in darkness,” but she promised to continue her husband’s work and keep publishing books in Bangladesh. In fact 12 July 2018 was Dipan’s birthday and Jose Borghino, Secretary General, IPA tweeted:

Today we celebrate the birthday of Faisal Arefin Dipan, the Bangladeshi publisher who was brutally murdered by religious fanatics in 2015 and was awarded the IPA's Special Prix Voltaire this year. His wife, Razia Rahman Jolly, says: 'Dipan was murdered and we lost our sunshine.'

— José Borghino (@JoseBorghino) July 12, 2018

Months after the panel discussion was recorded at the IPA in Delhi, prominent Tamil publisher Kannan Sundaram, Kalachuvadu Publications, who is known for publishing Perumal Murugan, delivered a talk at the May Sahitya Mela in Dharwad, Karnataka, on May 26. It was published as an article for Scroll “As intolerance grows, India needs a brand of secularism that keeps a distance from religion, caste: Today, majoritarian fundamentalism is the biggest threat to a writer and an artist’s free expression.” ( 9 July 2018) This is what Kannan Sundaram says:

If one truly believes in freedom of expression, one has to fight to preserve the right of expression for ideas that one cannot stomach. For many people who consider themselves progressives, freedom of expression is often about fighting for the right to express only ideas they believe in. Some argue that freedom of expression is allowed only for rational thought. For ideas they consider regressive, they demand a ban and prosecution by the state. This strain of thought we know has led to the imprisonment and murder of writers throughout modern history by various regimes claiming to be revolutionary. Fascism can come from the right, left or centre of the ideological spectrum. It may come from any ideology or even from an ideological vacuum if people blindly and reverentially follow a demagogue.

In today’s context, majoritarian fundamentalism is the biggest threat to a writer and an artist’s free expression. If the Bharatiya Janata Party rules for another term, with full majority, it is sure to cause untold harm to the idea of India.

…

Intolerance is not a Hindutva creation. All ideologies, and political, religious movements and political parties in India have contributed to increasing intolerance. There is not one political party in India that has ever endorsed freedom of expression except mouthing it when it suits them. It is part of no political party’s manifesto. This soil was nurtured by intolerance over the decades by all political formations. Now, Hindutva has sown its seeds, watering it with blood and reaping it electorally. Yet, few have learnt the lesson. Hindutva intolerance cannot be met by anti-Hindutva intolerance. The real counter is to meet it with tolerance, discussion, debate, peaceful demonstration and campaigns – which are all, of course, relatively tougher options. We have to draw on the positive aspects of our tradition that have nurtured strong unifying points for different milieus and cultures.

Writers have always faced intolerance from family, neighbourhood, religion and caste. No government or party has ever supported their right to write. What is different now is that Hindutva organisations have been able to knit together multiple castes under their platform and launch major campaigns against writers or simply bump them off with hired killers.

…

A new definition of secularism in India has to define secularism as maintaining equidistance from all religious and caste formations.

The next important thing is to prepare a policy paper on freedom of expression and convince all secular parties to discuss and accept it.

Only time will tell how much freedom publishers and writers genuinely have, can they contribute to the cultural quotient as mentioned by Richard Charkin earlier at the congress or do many subscribe to the policy of self-censorship?

Read more about the congress on the IPA blog maintained by James Taylor.

13 July 2018

( My article on the preview for JLF 2017 was published on Bookwitty.com on 30 December 2016.)

The first time I attended the Jaipur Literature Festival (JLF) at Diggi Palace Grounds, Jaipur it was small enough so that once could drive the car straight up to the main steps of the building. Today, the parking is a fair distance from the palace and the only way to reach the venue is through multiple barricades and a screening counter. Once inside though, there is a wonderful, festive air with an explosion of colours in the décor, the happy buzz of excited people milling about and conversations streaming through various marquees. Termed one of the greatest literary events, it is also a free one. Since it began, the JLF has welcomed 846,000 visitors, 1874 speakers, conducted 1272 sessions and partnered with more than 1400 organisations.

The JLF is also crucial because it is situated in a geographical space that is at the heart of a significant book market. It is planned soon after the Christmas break and a few months after the Frankfurt Book Fair (FBF) so publishing professionals flying in from around the world can follow up on their FBF conversations and combine them with a holiday in India.

In January 2017, it will be the 10th anniversary of the Jaipur Literature Festival. The three directors since its inception are Sanjoy Roy, Namita Gokhale and William Dalrymple. The festival has evolved over the years to include different elements such as Jaipur BookMark – a B2B platform for publishers, a children’s section and a cultural event every evening. The Festival has expanded internationally to host annual events at London’s Southbank Centre (2014 onwards) and Boulder, Colorado (2015 onwards). In 2017 the Jaipur BookMark will launch a new scheme to support emerging writers and budding authors are invited to apply for a New Writers’ Mentorship Programme: The First Book Club.

The Festival has celebrated and hosted writers from across the globe, ranging from Nobel Laureates and Man Booker Prize winners to debut writers, including Amish Tripathi, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Eleanor Catton, Hanif Kureishi, His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama, Ian McEwan, JM Coetzee, Margaret Atwood, Mohammed Hanif, Oprah Winfrey, Orhan Pamuk, Pico Iyer, Salman Rushdie, Stephen Fry, Thomas Piketty, Vikram Seth and Wole Soyinka, as well as renowned Indian language writers such as Girish Karnad, Gulzar, Javed Akhtar, MT Vasudevan Nair, Uday Prakash, the late Mahasweta Devi and U.R. Ananthamurthy.

This January, the Jaipur Literature Festival expects to welcome over 250 authors, thinkers, politicians, journalists, and popular culture icons to Jaipur. Sanjoy Roy said “Our prime focus is on history of the world, given that it was the 70 years of India’s Independence [in 2016]. In a new collaboration with the British Library they have loaned us a version of the 1215 AD Magna Carta which will be on view at Diggi Palace. A series of sessions on freedom to dream will look at inspiration for the future. We have a new partnership with The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) that will look at sessions on art and migration.”

Namita Gokhale added that at the JLF “We are always trying to listen in as many languages as possible. This time there will be speakers from all over Europe and more than 20 Indian regional languages will be showcased.”

Controversies and the JLF also seem to go hand in hand. In 2012 Hari Kunzru, Ruchir Joshi, Amitava Kumar and Jeet Thayil read out passages from Salman Rushdie’s banned book The Satanic Verses and had to leave Jaipur hurriedly before the police arrived to arrest them. Another time the Shell oil company was one of the sponsors, which created a stir since, among other things, it is infamously associated with the tragic execution of Nigerian writer Ken Saro-Wiwa. At the time, the JLF administration said they do not look at the color of money. This year too, there is disappointment already being expressed at representatives of the Hindu fundamentalist group RSS being invited to speak at JLF but as the organizers point out they stand for diversity.

Be that as it may, the 2017 edition of JLF promises to be as exciting as ever. The magnificent line-up of authors includes Paul Beatty, Alan Hollinghurst, Valmik Thapar, Amruta Patil, AN Wilson, Alice Walker, Mark Haddon, Ajay Navaria, Mrinal Pande, Richard Flanagan, Arshia Sattar, Arefa Tehsin, Eka Kurniawan, Tahmima Anam, Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni, Marcos Giralt Torrente, Kyoko Yoshida, David Hare, Margo Jefferson, Deborah Smith, Jeremy Paxman, Hyeonseo Lee, Francesca Orsini, John Keay, Jon Wilson, Kate Tempest, Mihir S. Sharma, Neil MacGregor, Rishi Kapoor, Sholeh Wolpé, Sunil Khilnani, and Vivek Shanbhag. Sessions have been planned on translations, revisiting history, conflict, politics, memoirs, biographies, nature, poetry, spirituality, mythmaking, women writing, travel writing, freedom of expression, children’s literature and book releases.

Some of the prominent sessions are:

Writing the Self: The Art of Memoir: Bee Rowlatt, Brigid Keenan Emma Sky and Hyeonseo Lee in conversation with Samanth Subramanian

Lost in Translation: Francesca Orsini, Deborah Smith, Paulo Lemos Horta and Sholeh Wolpé in conversation with Adam Thirlwell

Migrations: Lila Azam Zanganeh, NoViolet Bulawayo, Sholeh Wolpé and Valzhyna Mort in conversation with Tishani Doshi

The Tamil Story: Imayam Annamalai and Subhashree Krishnaswamy in conversation with Sudha Sadhanand

In Search of a Muse: On Writing Poetry: Anne Waldman, Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir, Ishion Hutchinson, Kate Tempest, Tishani Doshi and Vladimir Lucien in conversation with Ruth Padel

Lost Kingdoms: The Hindu and Buddhist Golden Age in South East Asia: John Guy introduced by Kavita Singh

Before We Visit the Goddess: Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni in conversation with Shrabani Basu

Kohinoor: Anita Anand and William Dalrymple introduced by Swapan Dasgupta

The Dishonourable Company: How the East India Company Took Over India: Giles Milton, John Keay, Jon Wilson, Linda Colley and Shashi Tharoor in conversation with William Dalrymple

Brexit: A.N. Wilson, Andrew Roberts,, Linda Colley, Surjit Bhalla and Timothy Garton Ash in conversation with Jonathan Shainin

Rewriting History: The Art of Historical Fiction: Adam Thirlwell, Alan Hollinghurst and Shazia Omar in conversation with Raghu Karnad

Civil Wars: From Antiquity to ISIS: David Armitage introduced by Raghu Karnad

The Biographer’s Ball: A.N. Wilson, Andrew Roberts, David Cannadine, Lucinda Hawksley, Roy Foster and Suzannah Lipscomb in conversation with Anita Anand

Ardor: On the Vedas: Roberto Calasso in conversation with Devdutt Pattanaik

Things to Leave Behind: Namita Gokhale in conversation with Mrinal Pande and Sunil Sethi

That Which Cannot be Said: Hyeonseo Lee, Kanak Dixit, Sadaf Saaz and Timothy Garton Ash and in conversation with Salil Tripathi

The Art of the Novel: On Writing Fiction: Adam Thirlwell, Alan Hollinghurst, NoViolet Bulawayo and Richard Flanagan in conversation with Manu Joseph

Footloose: The Travel Session: Aarathi Prasad, Bee Rowlatt, Brigid Keenan, Nidhi Dugar and Simon Winchester in conversation with William Dalrymple

The JLF 2017 will run from January 19-23rd.

( I wrote an article for the amazing literary website Bookwitty.com on “Penguin on Wheels”. An initiative of Walking BookFairs and Penguin Books India. It was published on 28 June 2016. Here is the original url: https://www.bookwitty.com/text/penguin-on-wheels-walking-bookfairs-and-penguin-b/57725752acd0d076db037bf7 . I am also c&p the text below. )

( I wrote an article for the amazing literary website Bookwitty.com on “Penguin on Wheels”. An initiative of Walking BookFairs and Penguin Books India. It was published on 28 June 2016. Here is the original url: https://www.bookwitty.com/text/penguin-on-wheels-walking-bookfairs-and-penguin-b/57725752acd0d076db037bf7 . I am also c&p the text below. )

Literature does not occur in a vacuum. It cannot be a monologue. It has to be a conversation, and new people, new readers, need to be brought into the conversation too.”

-Neil Gaiman, Introduction, The View from the Cheap Seats ( 2016)

On the 16th of May 2016, Penguin Random House India circulated a press release about Penguin Books India’s one-year collaboration with Walking BookFairs (WBF) to launch “Penguin on Wheels”, a bookmobile that will travel through the eastern Indian state of Odisha promoting reading and writing.

This is not the first time Walking BookFairs has collaborated with a publishing house to promote reading. Their earlier “Read More, India” campaign saw Walking BookFairs supported by HarperCollins India, Pan MacMillan India, and Parragon Books India. Apart from these three publishers, WBF stocked books from various other publishers, including Tara Books, Speaking Tiger Books, Penguin, Duckbill, Karadi Tales, and Scholastic. “We got books delivered by our publishers on the road wherever we were displaying books.”

The concept of bookmobiles is not unusual in India, for some decades the state-funded publishing firm, National Book Trust, has maintained its own book vans. Yet it is the duo of Satabdi Mishra and Akshaya Rautaray that has captured the public imagination.

Walking BookFairs was established two years ago while Satabdi Mishra was on a break from her job and Akshaya  Rautaray quit his publishing job to set up an independent “simple bookstore” in Bhubaneshwar. The shop, which they prefer to think of as a “book shack”, runs on solar power. It is a simple space with the bare necessities and a garden. They allow readers to browse through the bookshelves, offering a 20-30% discount on every purchase throughout the year.

Rautaray quit his publishing job to set up an independent “simple bookstore” in Bhubaneshwar. The shop, which they prefer to think of as a “book shack”, runs on solar power. It is a simple space with the bare necessities and a garden. They allow readers to browse through the bookshelves, offering a 20-30% discount on every purchase throughout the year.

WBF also doubles as a free library. They introduced the bookmobile in 2014, as part of an outreach programme that would see them travelling to promote reading in the state. Speaking to me by email, Satabdi said,

“There are no bookshops or libraries in many parts of India. There are thousands of people who have no access to books. We started WBF in 2014 because we wanted to take books to more people everywhere. We have been travelling inside our home state Odisha for the last two years with books. We found that most people do not consider reading books beyond textbooks important in India. We wanted people to understand that reading story books is more important than reading textbooks. We wanted to reach out to more people with books. We also wanted to inspire and encourage more people across the country to read books and come together to open more community libraries and bookshops.”

India is well known for stressing the importance of reading for academic purposes rather than reading for pleasure. In a country of 1.3 billion people, where 40% are below the age of 25 years old, and the publishing industry is estimated to be of $2.2 billion, there is potential for growth. Indeed,there has been healthy growth across genres, quite unlike most book markets in the world.

The WBF team has been keen to promote reading since it is an empowering activity. They began in the tribal district of Koraput, Odisha, where they carried books in backpacks and walked around villages. They displayed books in public spaces like bus stops and railways stations or spreading them out on pavements or under trees, whatever was convenient and accessible. “That works because people in smaller towns feel intimidated by big shops,” they say.

Apart from public book displays, they also visit schools, colleges, offices, educational institutions, and residential neighbourhoods. They soon discovered that children and adults were not familiar with books. Bookstores too seem only to be found in urban and semi-urban areas and are lacking in rural areas, but once easy access to books is created there is a demand. As Neil Gaiman says in the essay “Four Bookshops”, these bookshops “made me who I am”, but the travelling bookshop that came to his day boarding school was “the best, the most wonderful, the most magical because it was the most insubstantial”. (The View from the Cheap Seats)

Speaking again via email, Satabdi says that they’ve found, “Children’s books are always the most sought after. We have many interesting children’s storybooks and picture books with us. We found that in many places, not just children but also adults and young people enthusiastically pick up children’s books, browse through and read them. Beyond a couple of urban centres in India, big cities, there are no bookshops. Most bookshops that one comes across are shops selling textbooks, guide books or essay books. Many people were actually looking at real books for the first time at WBF.”

In India the year-on-year growth rate for children’s literature is estimated to be 100%. Satabdi Mishra and Akshaya Rautaray stock 90% fiction. Rautaray says, “We believe in stories. I think, if you need to understand the world around you, if you need to understand science and history and sociology, you need to understand stories. I believe in a good book, a good story.”

The categories include literary fiction, classics, non-fiction, biographies, books on poetry, cinema, politics, history, economics, art visual imagery, young adult, picture books, children’s books, and regional literature from Odia and Hindi. The emphasis is on diversity, but they do not necessarily stock bestsellers or popular books like romance, textbooks, or academic books. That said, the Penguin on Wheels programme will dovetail beautifully with, “Read with Ravinder” another of the publisher’s reading promotion campaigns, spearheaded by successful commercial fiction author Ravinder Singh.

In December 2015, Satabdi and Akshay launched their “Read More, India” campaign (#ReadMoreIndia), which saw them take their custom-built book van, loaded with more than 4000 books across India. They covered 10,000kms, 20 states, in three months (from 15th Dec 2015 to 8th March 2016).

Over the course of the journey, they sold forty books a day, met thousands of people, and had a number of interesting experiences. One anecdote that gives an insight into the passion and trust that the young couple displays is of that of an elderly gentleman in Besant Road Beach road, Chennai. The older man was out for his daily jog and stopped to look at the books. He wanted to buy some books, but had left his wallet behind.

“We asked him to take the books and pay us later via cheque or bank transfer. He seemed surprised that we were letting him take the books without paying. He took the books and sent the money later with his driver. We want people to read more books. And if people cannot buy books, we want them to read books for free for as long as they want. People pay us in cash, in kind, sometimes they take books pay later, pay through credit/debit cards.”

The Penguin on Wheels campaign was launched because Penguin Books India had been following WBF’s activities and reached out to them. Earlier, they had collaborated for an author event in Odisha, but this new move is a focussed effort that will see the bookmobile travel within Odisha.

The books are curated by Akshay as Penguin Books India said graciously that “they [WBF] know best what their readers like more”. It will consist of approximately 1000 titles from the Penguin Random House stable. The collection will have books by celebrated authors, including Jhumpa Lahiri, John Green, Orhan Pamuk, Amitav Ghosh, Devdutt Pattanaik, Salman Rushdie, Ravinder Singh, Twinkle Khanna, Hussain Zaidi, Khushwant Singh, Roald Dahl, Ruskin Bond, and Emraan Hashmi.

Contests and author interactions will also be organised with the support or Penguin Random House. It will start with Ravinder Singh’s visit to Bhubaneshwar for the promotion of his newly launched book, Love that Feels Right. Satabdi Mishra adds, “We are happy to partner with PRH through the WBF ‘Penguin on Wheels’ that will spread the joy of reading around.”

Jaya Bhattacharji Rose

28 June 2016

History is unkind to those it abandons, and can be equally unkind to those who make it. (p14)

History is unkind to those it abandons, and can be equally unkind to those who make it. (p14)

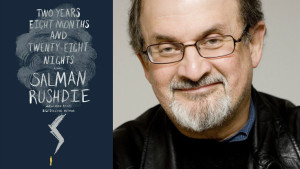

Salman Rushdie’s latest book, Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights is fiction like nothing before it. It is in the same class as Midnight’s Children —ground breaking literary fiction. Like the One Thousand and One Nights that it echoes in its title it is an intricate web of stories within stories, which showcase Rushdie’s technical, verbal and literary expertise. It is tales within tales spread over many centuries. It is about a Djinn, Duniya, and her love for a human – Ibn Rashd better known in the West as Averroes– and their family. ( Ibn Rashd was also the name Rushdie’s grandfather adopted and adapted to created his surname. “Rushdie” is not an inherited family name.)

He has created a world, sufficiently far-off in the future to create and discuss life today without really disturbing anyone’s equanimity in the present. It is very hard not to consider parts of it as being autobiographical, particularly when the authorial narrative intrudes to comment upon war, freedom, choices made as humans etc. Although in an interview with poet Tishani Doshi for the Hindu, Rushdie says categorically that autobiography is less and less important for him. He writes “something original and strange and unusual, and now there’s a mood for real life stories and so my book is the kind of anti- Knausgård”. ( http://bit.ly/1OmOcla ) Yet it is hard to separate the two parts of a man — the lived/autobiographical element and the literary fiction. For a man who has lived under the shadow of a fatwa, he has lived daily with the fear of death, much like Scheherazade the narrator of One Thousand and One Nights. In Rushdie’s case, it has made him fearless and outspoken. His speeches and articles on freedom of expression are admirable for their clarity and sharpness. For instance, listen to Rushdie at the India Today Conclave on 18 March 2012: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tNzGgYvz92s . It is this confident, breezy style evident in his literary experimentation. From his very first novel it has been evident but over time it has been taken to another level — another landmark in modern literary fiction for writers to admire, probably emulate.

In Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights Rushdie sparkles when his anger simmers through the novel, but at first glance it does not seem so to exist. It just seems like a magic realism tale where innumerable characters waltz on and off the page as and when they need to play their parts. There is little time for the reader to create a “bond” with any character save for a tenuous one with Geronimo the levitating gardener. It is more like a manifesto of Rushdie’s experiences as a writer. In a Paris Review interview of 2005, he had said: “My life has given me this other subject: worlds in collision. How do you make people see that everyone’s story is now a part of everyone else’s story? It’s one thing to say it, but how can you make a reader feel that is their lived experience?” (Salman Rushdie, The Art of Fiction No. 186 Interviewed by Jack Livings, The Paris Review, Summer 2005, No 174 http://bit.ly/1OmU2Tv ) This twelfth novel too is like an amalgamation of his experiences — cultural and literary — brought forth as a fabulist tale. It can be read for what it is at first reading or appreciated for its multiple layers. Richness of the text lies in the degree of engagement you can have with it as a reader. Ironically this novel makes a mockery of the information-overloaded age since many of the literary, cultural, political, historical and linguistic references are acquired over a period of time with reading and experience. The text cannot be deciphered by looking up references on Wikipedia. It won’t make the text work satisfactorily. Rushdie is delightfully unapologetic about blending languages and cultural references. He is what he is. This is it.

In the 2005 Paris Review interview Rushdie had been asked, “Could you possibly write an apolitical book?”. He had replied, “Yes, I have great interest in it, and I keep being annoyed that I haven’t. I think the space between private life and public life has disappeared in our time.”

If possible, read Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights in conjunction with Joseph Anton, his memoir. But read you must.

Here are links to some recent articles and interviews with Rushdie published to coincide with the launch of Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights.

Rushdie interviewed by Tishani Doshi in The Hindu, 13 September 2015. ” ‘I kind of got sick of the truth’ ” ( http://bit.ly/1OmOcla)

Nilanjana Roy’s wonderful analysis of the novel in Business Standard, 7 September 2015. “2.8.28: More hit than myth” ( http://bit.ly/1OmP0qe )

Salil Tripathi’s review-interview with Rushdie in The Mint, 4 September 2015. “Salman Rushdie: ‘I have no further interest in non-fiction’ ” ( http://bit.ly/1OmQnVW )

A profile in the Guardian. An interview conducted in Rushdie’s literary agent, Andrew Wylie’s office, by Fiona Maddocks, 6 September 2015 “Salman Rushdie: ‘It might be the funniest of my novels’ ” ( http://bit.ly/1OmNtAn )

Ursula le Guin’s review in the Guardian, 4 September 2015 “Two Years, Eight Months and Twenty‑Eight Nights by Salman Rushdie review – a modern Arabian Nights” ( http://bit.ly/1OmNKDF )

An interview with Alexandra Alter in the New York Times, 4 September 2015. “Salman Rushdie on His New Novel, With a Character Who Floats Just Above Ground” (http://nyti.ms/1OmPhJU )

“The novel is vividly described and rich in mayhem – Isn’t this mayhem reminiscent of the knowledge we carry in our head” Eileen Battersby in the Irish Times, 12 September 2015. “Two Years Eight Months & Twenty-Eight Nights review: Rushdie on overdrive” ( http://bit.ly/1OmPWec )

Salman Rushdie Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights Hamish Hamilton, an imprint of Penguin Books India, Gurgaon, 2015. Hb. pp. 290 Rs 599

13 September 2015