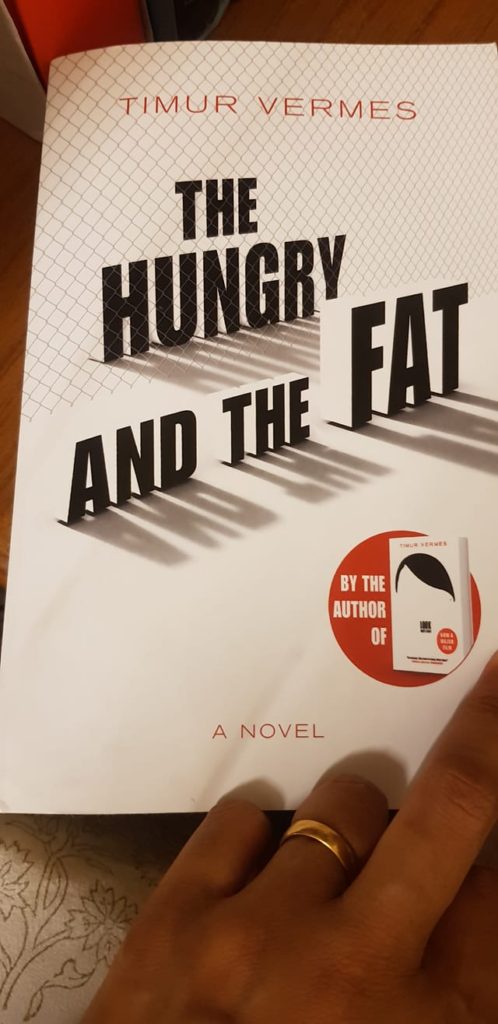

Timur Vermes, “The Hungry and the Fat”

The broadcaster has pretty much freed up the whole schedule for him that day. The Grand Prix has been booted off and they’ve given him the evening slot, 8.15pm., when they usually put on a Hollywood blockbuster. To transmit the showdown. Hundreds of thousands of migrants marching live to the Turkish border, with nobody knowing how the guards are going to react. The most appealing refugees at the front, women and children, with no certainty they’ll survive the evening. It’ll be the most exciting news broadcast since the fall of the Berlin Wall, with one of Germany’s most beautiful women as its star. A dozen teams of drones, pictures from every angle, a hundred refugees wired up to cameras and transmitters, images from right next to the fence, even if shots are fired.

“Just picture it,” Sensenbrink said to the small gathering of top executives. “The Turks shoot, we check the images in the production control room and you get it all: the flinching, the fear, the panic. These brave people can’t go away and don’t want to, we see it, we hear the original sound, then camera 52 wobbles, the director notices and immediately switches, but camera 52 goes down, two more shots and there’s slight movement to begin with. And then” — Sensenbrink paused briefly –“then …nada. And we see an unchanging picture from ground level. A little crooked, a final movement …then…it remains static.”

Nobody stirred. Fifteen or twenty seconds of silence before Karrner said, half in jest, “Maybe it just fell over.”

To which Sensenbrink calmly replied, “Yes, maybe.”

At that moment he had Sunday in the bag. Five hours of live broadcasting. And open-ended too.

Timur Vermes second novel The Hungry and the Fat is as to be expected, excellent satire. It has been translated from German into English by Jamie Bulloch. The bare outline of the story is a model and star presenter, Nadeche Hackenbrunch, decides to shoot reality TV from a refugee camp in Africa. The ratings begin to go north rapidly. The programme is extended by fifteen minutes to accommodate all the commercials so as not to seem to insensitive of broadcasting an infocommericial with a few snippets of refugees thrown in. To keep the audience engaged, the TV crew, encouraged by their interpreter, Lionel, decide to film in real time a refugee march to Germany. It begins to erupt in ways more extraordinary than ever suspected by any of the participants. In short, it becomes an international incident.

The Hungry and the Fat is satire at its best. If the aim of satire is to put the spotlight on society’s attitudes towars refugees and the complicated situations it can give rise to, then this novel does it remarkably well. It is not very easy to read as the line dividing fiction and reality is barely discernible. What is the truth? What is manipulated? What is reality television? Is it humane to be milking such misery, poverty and hunger for the sake of commercial TV? Even when the story proceeds beyond the tragic march, the stories of the individuals like Nadine, attain a proportion that is unexpected. Without giving away too much of the plot, suffice it to say it is ironic that she achieves the levels of recognition she yearned for but could not experience. And this is the cruelty of reality television of making heroes of individuals rather than focusing on the more problematic issues at stake of humanity, breakdown of socio-political and economic systems and the lack of governance to create such horrific manmade tragedies. While Timur Vermes can easily be reckoned to be the modern master of satire, his second novel is not exactly in the same league as his debut Look Who’s Back (2014) which sold more than a million copies in German. Nevertheless, The Hungry and the Fat has plenty to mull over. It is an unsettling but essential read.

1 July 2020