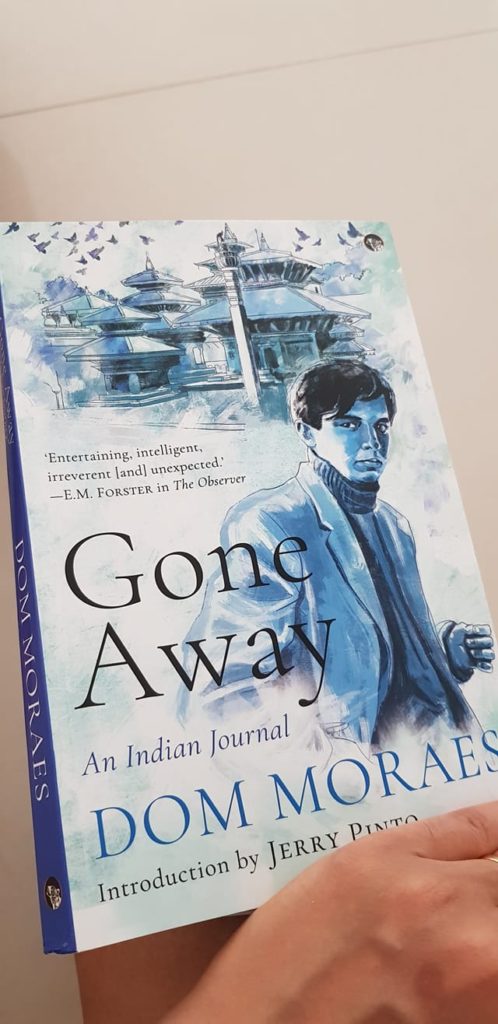

“Sin” by Wajida Tabassum, translated from the Urdu by Reema Abbasi

This is a Muslim Syed girl from a family where liberties for women were thought odious. My father forbade us to attend school and purdah was our bounden duty. My parents passed away when I was three years old and a paternal uncle persuaded our grandmother to educate us. She relented, keeping a lidless eye on each of us.

My third sister was bright and obstinate, with great love for books. She listened intently to every story, which slowly became an obsession. At only three, she forced Nani to enroll her in a school. As time went by, she read, and with her passion came to a gradual swell.

Several magazines — Shamaa, Jamalistaan, Ariyavarat, Kaamyaab and more — could be found in our house. I leafed through them, attentive OR clutching on to every word. The groceries were wrapped in pages torn out of magazines and I read every line on them. They were more exciting than journals. I took them into obscure corners to scan through the incomplete stories. It felt like all the knowledge in the world was mine.

I have a Master of Arts degree and the impulse to know every word ever written soars as despeerately as it did when I was a girl in the fifth standard. However, my passion was tied to our situation. To us, money was a lofty reverie, like a gulp of the sun. The desire to go to markets, exploer bookshops and buy literature caved before our meagre means.

….

I could not buy a book. When I asked for one, she refused and said that such books were unsuitable for girls from aristocratic families. Nani had vowed to keep us away from them … .

…Books were my source of light and warmth.

… A book was always with me. My novels snug in school books, I basked in their language and immersive imagery through the exams too. …

…books became my refuge and my friends. In school, my performance was seen as exemplary and pleased teached accepted my many requests for books from the library. These became the happiest days of my life. I would go through a book in two hours and would immediately pick up another one.

….In Hyderabad, the rules of our library were rigid and the shrunked stock of books hit me the hardest. Once a week, a girl could get one book at a time. ….

One morning, I was humming in class and a girl at the opposite desk said, “Wajida, please sing a little louder.”

My were were fixed on Munshi Premchand’s Godaan in her hand.

“On one condition,” I replied.

“What?”

“I will sing for you if you lend me your book,” I negotiated.

She agreed. I sang.…

The next moment, her book was in my hands. Soon after, books flowed to me. I sang to get them and girls from other classes began making similar deals with me — books for songs. I was relentless. The world spread out in an immense space, crowded with writers and varied themes. The ones I read in my harsh circumstances brought smiles and pride. However, as I write these lines, I am sad to think that this, like a sip of air, was a trivial scale.

…

Wajida Tabassum’s ( 16 March 1935 – 7 December 2011) was an Urdu writer. She was known for her “audacious and semi-erotic stories and her formidable power of storytelling”. She was born into an aristocratic family but her parents lost their wealth and died very young too. By the time she was three, Wajida Tabassum was an orphan. Her maternal grandmother, Nani, brought up the eight children. These were tough times and they were poor. Wajida Tabassum was a voracious reader with a flair for writing and she put it to good use by contributing short stories to magazines. Soon, she was being spoken of and as she mentions in her autobiographical essay, “Meri Kahaani” ( My Story), that soon the very same relatives who had earlier shunned them, were now readily acknowledging her.

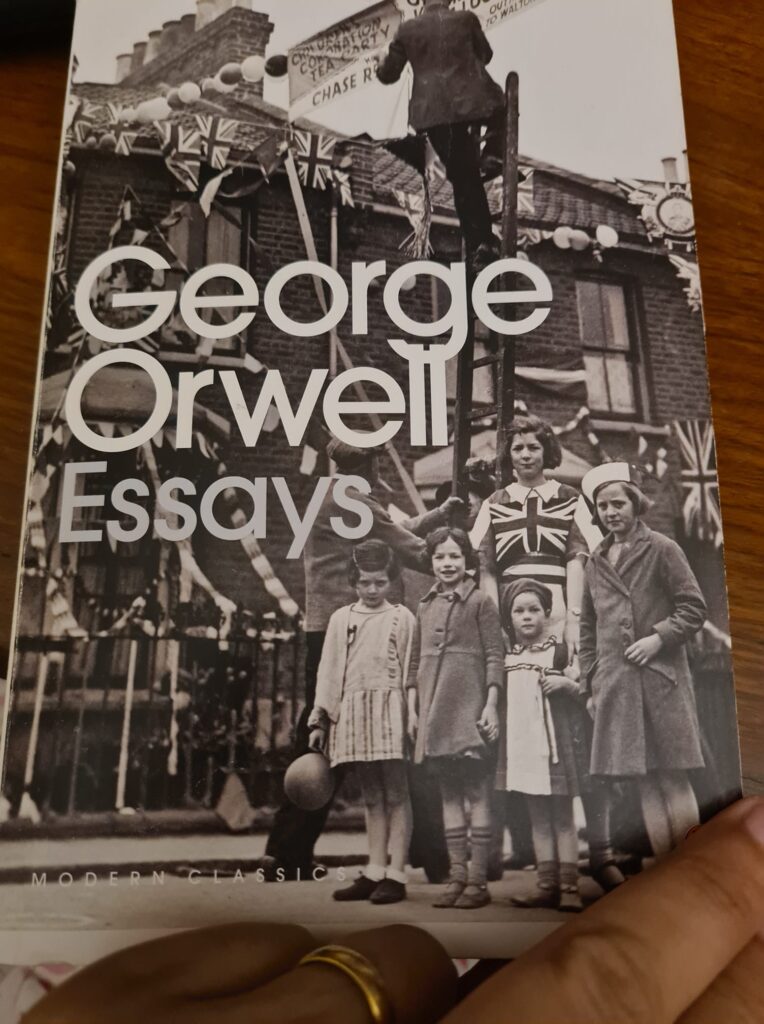

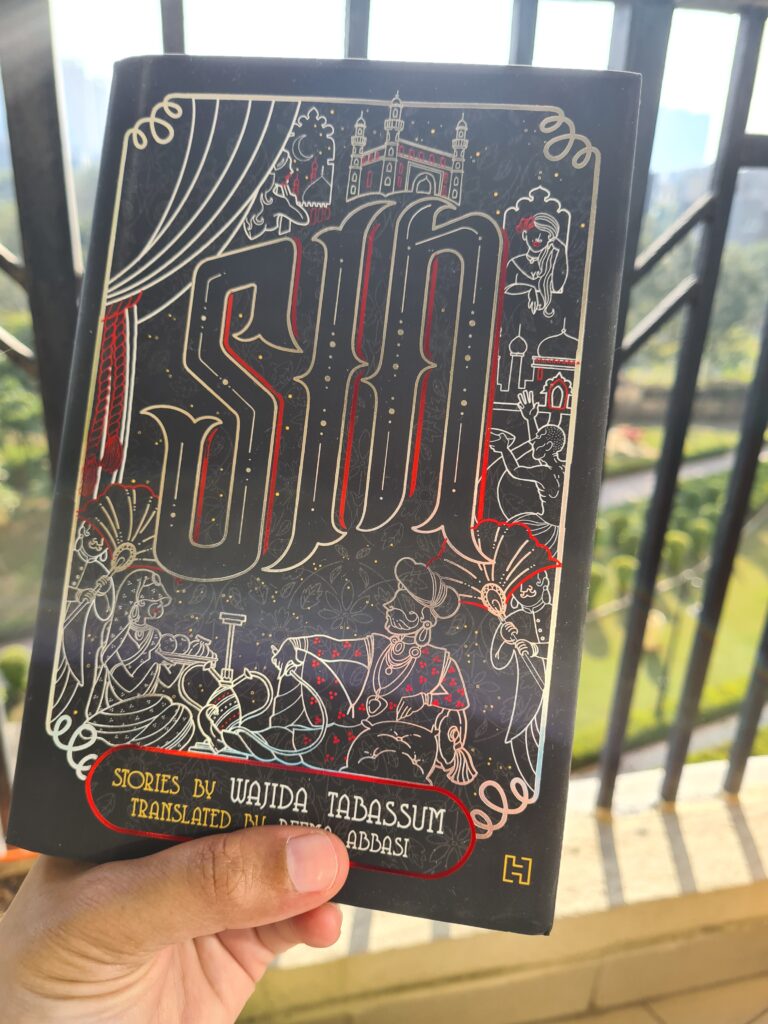

Sin is a collection of nineteen short stories translated by Reema Abbasi ( Hachette India). It also marks the first time that Wajida Tabassum’s stories are being translated into English. According to the translator, the four sections in thevolume deal with “dark, debauched and tragic aspects of life and are structured on the theme of the ‘deadly sins’, namely, lust, pride, greed and envy. The stories are translated competently though at times certain Urdu words could do with a little more explanation through the context. Unfortunately, I did not maintain a list while reading but kept wondering about the meaning of the words. Having said that, the stories are well translated. Structurally to place “My Story” in the middle of the book is a very good idea as it provides a break from the stories. In many ways, the stories seem bold by contemporary standards of writing as well. But clubbing so many together seems to diminish their oomph factor. Perhaps, if they had been arranged chronologically, according to the date of publication, then the growth of the writer would also have been evident. For now, the stories are enjoyable but in small doses.

Once the stories are read, then Wajida Tabassum’s rant about be open to stories rather than being led by the nose becomes obvious in paragraphs such as this about endorsements. She is so clear about her views.

In our literature, forewords have become customary. I feel they lean our readers in a certain direction, which is worrying. Why do we need a renowned name to endorse our work to the extent that critique is printed onthe dust cover? I have many letters from celebrated writers, who applaud my work. Many of them are dear to me. They would compose a preface in an instant. But I disagree with the idea. The foreword to me is a diversion for the reader’s mind and a tool of cheap publicity. When someone wants to move ahead, they should walk without a crutch. Even if they means taking an uneasy road to the last stop.

This kind of sharp clarity is required in more and more writers of today. Perhaps the resurrection of a powerful women writer such as Wajida Tabassum in English will ensure that not only is she read far and wide but she inspires and influences new generations of writers to share their opinions in an equally forthright manner.

Sin is definitely a collection of short stories worth recommending.

2 Feb 2022