Book Post 31: 17-27 March 2019

Every week I post some of the books I have received recently. In today’s Book Post 31 included are some of the titles I have received in the past few weeks.

28 March 2019

Every week I post some of the books I have received recently. In today’s Book Post 31 included are some of the titles I have received in the past few weeks.

28 March 2019

Preeto & Other Stories : The Male Gaze in Urdu is a collection of short stories edited and introduced by noted writer and translator Rakhshanda Jalil. This extract is taken from her fabulous introduction that gives a broad overview of Urdu writing. While there is a detailed portion on Urdu women writers the selected extract focuses on the reasons for Rakhshanda Jalil’s selection with a brief commentary on the male writers she chose to include in the anthology.

This extract is published with the permission of the publishers Niyogi Books.

***

The woman has been both subject and predicate in a great deal of writing by male writers. In poetry she has, of course, been the subject of vast amounts of romantic, even sensuous imagery. Be it muse or mother, vamp or victim, fulsome or flawed, there has been a tendency among male writers to view a woman through a binary of ‘this’ or ‘that’ and to present women as black and white characters, often either impossibly white or improbably black. Since men are not expected to be one or the other but generally taken to be a combination of contraries, such a monochromatic view inevitably results in women being reduced to objects, of being taken to be ‘things’ rather than ‘people’. That this objectification of women, and the consequent dehumanisation, effectively ‘others’ half the human population seems to escape many writers, even those ostensibly desirous of breaking stereotypes or those who see themselves as liberal, even emancipated men. Films, television and media have traditionally aided and abetted the idea that women are objects to be pursued and eventually won over like trophies or prizes. Literature has fed into the trope that women are bona fide objects of sexual fantasy, or blank canvases on which men can paint their ideals, or even empty vessels into which they can pour their pent-up feelings and emotions.

Feminist theoreticians would have us believe that there is, and has always

been, a traditional heterosexual way of men looking at women, a way that

presents women as essentially sexual objects for the pleasure of the male

viewer. The feminist film critic Laura Mulvey, in her seminal essay ‘Visual

Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ (1975), termed this way of seeing as the ‘male

gaze’. Mulvey’s theory was based on the premise that ‘an asymmetry of power

between the genders is a controlling force in cinema; and that the male gaze is

constructed for the pleasure of the male viewer which is deeply rooted in the

ideologies and discourses of patriarchy’. Within a short span of time, the

expression slipped into accepted usage and moved seamlessly across medium: from

film to literature to popular culture. Today, we use the term loosely to

describe ways of men seeing women and consequently presenting or representing

them.

In the context of Urdu, I have always been intrigued by how men view women and, by extension, write about them. For that matter, I am equally intrigued by how women view women and the world around them. In fact, as a precursor to this present volume, I had edited a selection of writings in Urdu by women called Neither Night Nor Day (Harper Collins, 2007). I had set myself a deliberately narrow framework by looking at women writers from Pakistan as I was curious to discover how women, in an essentially patriarchal society, view the place of women in the world. I chose 13 contemporary women writers and tried to examine the image and representation of women by women.

Now, ten years later, I have attempted to do the same with male writers, except that this time I have chosen Indian writers. While I have begun with two senior writers, Rajinder Singh Bedi and Krishan Chandar, I have chosen not to go back to the early male writers such as Sajjad Hyder Yildrum, Qazi Abdul Ghaffar or even Premchand, for that matter, who wrote extensively on women. For the purpose of this study, I wanted to make a selection from modern writers. In a world where more women are joining the work force, where ever more are stepping out from their secluded and cloistered world and can be physically seen in larger numbers, I was curious to see how, then, do male writers view and consequently present or represent the women of their world.

….

My task was made easy by two progressives — Rajinder Singh Bedi and Krishan Chandar — who continued to be active long after the progressive writers’ movement had petered off. Nurtured by a literary movement and a body of writers that prided in looking at women as comrades-in-arms, both have written powerful female characters but both can be occasionally guilty of a sentimentalism, a tendency to idealise a woman in an attempt to appear even-handed. The first story in this collection, ‘Woman’ (‘Aurat’) by Bedi shows the writer struggling to shake off a centuries-old conditioning, one that sees a woman as a nurturer, a preserver of a life force no matter how flawed or frugal that life force might be. A father might be willing to get rid of a child that is less-than-perfect, a bit like a vet that puts diseased or broken animals to sleep, but a mother can never envisage such an idea. Added to this view is the familiar trope of unrequited love, that too for a damsel in distress, of a male viewer drawn to a woman who loves her child unconditionally. This ability to love makes everything about her so attractive: ‘I don’t know if she was beautiful in real life but in my fantasy she was extremely attractive. I really liked the way she patted her hair in place. She would flick her hair off her face, stroke them in place with her fingers, stretching her hands all the way behind her shoulders — making it so difficult for me to decide if this was a conscious habit or an involuntary action.’

Krishan Chandar’s ‘Preeto’, also the title story for this collection, has two seemingly unrelated tracks that converge in a most unexpected manner: both lead to a point where the woman is eventually perceived as beautiful and enigmatic, the depths of whose heart can never be plumbed by a man. While one track leads to a gruesome tragedy, the other leads nowhere. The parallel tracks meet at a point of sorrowful acknowledgement: ‘A woman never forgets. Those people do not know women who think she comes to your home in a palanquin, sleeps on your bed, gives you four children and in return you can snatch her dream away, such people don’t know women. A woman never forgets.’ A man may love her and pamper her but there is no knowing that she will love him in return or that she will ever fully reveal what lies buried beneath seeming normalcy.

Gulzar heralds the onset of modernity in Urdu literature. In his story, a woman may work and play the field, she may find love outside marriage, she may stray as far as her former husband but she is still tethered to the yoke of motherhood, of being answerable to a man: in this case her son, a 13-year old boy who stops being her son the moment he turns a male gaze at her. The same son who is willing to stand up for her when she is a woman wronged, a victim, turns against her when she is perceived as a woman who has committed a wrong and set foot outside the proverbial lakshman rekha or line of chastity and honour. Gulzar’s ‘Man’ (‘Mard’) reminds us how ingrained these notions of honour are and how stringently women, more than men, must subscribe to them.

Faiyyaz Rifat’s ‘Shonali’ and Ratan Singh’s ‘Wedding Night’ (‘Suhaag Raat’) are classic instances of the male gaze: one is directed by an older man at a young nubile servant and the other at a maalan (a girl who tends a garden). In this thinly-disguised moral tale, the flowers are symbols of ‘pure’ love that a girl gives her groom on her wedding night. Both stories show a preoccupation with beauty and youth, a preoccupation that is also found in Baig Ehsas’s ‘A Heavy Stone’ ‘Sang-e Giran’ and Syed Muhammad Ashraf’s ‘Awaiting the Zephyr’ (‘Baad-e Saba ka Intizar’). Deepak Budki’s ‘Driftwood’ and Hussainul Haque’s ‘The Unexpected Disaster’ (‘Naa-gahaanii’) are troubling stories: the former makes a case for women who have been victims of abuse in childhood (incest in this case) becoming wayward and wilful as adults and the latter for victims of marital abuse having every reason to find love outside a loveless marriage yet refraining from doing so out of a sense of honour and uprightness. Both stories, in a sense, dwell on the notion of moral turpitude and its opposite, a dignity that men expect from women.

Zamiruddin Ahmad’s ‘A Bit Odd’ (‘Kuchh Ajeeb Sa’) is a niggling look at the idea of dignity, a quality that is intrinsic to women in a patriarchal world view and is only enhanced by the institutions of marriage, home, religion, domesticity. Abdus Samad probes a woman’s heart, scouring the ashes for a lambent flame in ‘Ash in the Fire’ (‘Aag Mein Raakh’): a thick blanket may douse a fire but beneath the ashes something will continue to smoulder. Rahman Abbas presents us with a contrarian view: What if a woman is self-avowedly asexual? What if she is willing to be a man’s friend and companion but nothing else? Will the male gaze continue to peer and prod looking for something that does not exist? What if a woman says ‘I don’t feel any need. I’m a dry river’? The woman in Siddique Alam’s ‘The Serpent’s Well’ (titled ‘Bain’ meaning ‘lamentation’ in the original but given this title by the translator) is as ancient as the forested heartland of India, and just as darkly mysterious.

To conclude, let me rest my case with these words by Milan Kundera in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting:

‘The male glance has often been described. It is commonly said to rest coldly on a woman, measuring, weighing, evaluating, selecting her — in other words, turning her into an object… What is less commonly known is that a woman is not completely defenseless against that glance. If it turns her into an object, then she looks back at the man with the eyes of an object. It is though a hammer had suddenly grown eyes and stare up at the worker pounding a nail with it. When the worker sees the evil eye of the hammer, he loses his self-assurance and slams it on his thumb. The worker may be the hammer’s master, but the hammer still prevails. A tool knows exactly how it is meant to be handled, while the user of the tool can only have an approximate idea.’

While a woman is certainly no tool, nor should she know how to be ‘handled’, there is something to be said for returning the gaze, of looking back. Perhaps if more women were to turn a steady gaze back at the beholder, there is no knowing what the ‘seeing eye’ will see.

Preeto & Other Stories : The Male Gaze in Urdu , Edited and introduced by Rakhshanda Jalil. Thornbird, an imprint of Niyogi Books, New Delhi, 2018. Hb. Pp. 200. Rs 450

8 March 2019

Every Monday I post some of the books I have received in the previous week. Embedded in the book covers and post will also be links to buy the books on Amazon India. This post will be in addition to my regular blog posts and newsletter.

In today’s Book Post 12 included are some of the titles I received in the past few weeks and are worth mentioning and not necessarily confined to parcels received last week.

Enjoy reading!

1 October 2018

It has been a hectic few weeks as January is peak season for book-related activities such as the immensely successful world book fair held in New Delhi, literary festivals and book launches. The National Book Trust launched what promises to be a great platform — Brahmaputra Literary Festival, Guwahati. An important announcements was by Jacks Thomas, Director, London Book Fair wherein she announced a spotlight on India at the fair, March 2017. In fact, the Bookaroo Trust – Festival of Children’s Literature (India) has been nominated in the category of The Literary Festival Award of International Excellence Awards 2017. (It is an incredible list with fantabulous publishing professionals such as Marcia Lynx Qualey for her blog, Arablit; Anna Soler-Pontas for her literary agency and many, many more!) Meanwhile in publishing news from India, Durga Raghunath, co-founder and CEO, Juggernaut Books has quit within months of the launch of the phone book app.

It has been a hectic few weeks as January is peak season for book-related activities such as the immensely successful world book fair held in New Delhi, literary festivals and book launches. The National Book Trust launched what promises to be a great platform — Brahmaputra Literary Festival, Guwahati. An important announcements was by Jacks Thomas, Director, London Book Fair wherein she announced a spotlight on India at the fair, March 2017. In fact, the Bookaroo Trust – Festival of Children’s Literature (India) has been nominated in the category of The Literary Festival Award of International Excellence Awards 2017. (It is an incredible list with fantabulous publishing professionals such as Marcia Lynx Qualey for her blog, Arablit; Anna Soler-Pontas for her literary agency and many, many more!) Meanwhile in publishing news from India, Durga Raghunath, co-founder and CEO, Juggernaut Books has quit within months of the launch of the phone book app.

In other exciting news new Dead Sea Scrolls caves have been discovered; in an antiquarian heist books worth more than £2 m have been stolen; incredible foresight State Library of Western Australia has acquired the complete set of research documents preliminary sketches and 17 original artworks from Frane Lessac’s Simpson and his Donkey, Uruena, a small town in Spain that has a bookstore for every 16 people and community libraries are thriving in India!

Some of the notable literary prize announcements made were the longlist for the 2017 International Dylan Thomas Prize, the longlist for the richest short story prize by The Sunday Times EFG Short Story Award and the highest Moroccan cultural award has been given to Chinese novelist, Liu Zhenyun.

Since it has been a few weeks since the last newsletter the links have piled up. Here goes:

New Arrivals ( Personal and review copies acquired)

14 February 2017

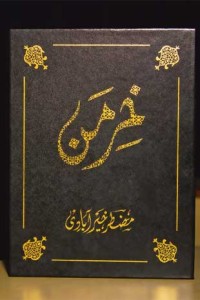

The Mint published a review by Rakhshanda Jalil on Muztar Khairabadi’s Khirman, now better known as Javed Akhtar’s grandfather. She gives a fantastic account of how the poems were discovered. Slowly, spread over many years, Muztar Khairabadi body of work was put together by collecting poems from personal collections and libraries. Authenticating the poems too was a labour of love. Last week the book was finally published and released in New Delhi, India. This is a good article to  read. http://www.livemint.com/Leisure/tde1HlP7hIatV65Icjbl6N/Lounge-Review-Muztar-Khairabadis-Khirman.html ( 12 Sept 2015)

read. http://www.livemint.com/Leisure/tde1HlP7hIatV65Icjbl6N/Lounge-Review-Muztar-Khairabadis-Khirman.html ( 12 Sept 2015)

Sadly what is missing are the book details. From what I hear this particular book has been self-published. Limited copies have been printed and priced at an exorbitant price of Rs 10,000. The book was released by the Vice President of India.

Sadly what is missing are the book details. From what I hear this particular book has been self-published. Limited copies have been printed and priced at an exorbitant price of Rs 10,000. The book was released by the Vice President of India.

14 September 2015

This year has been marked by the publication of Rakhshanda Jalil’s thesis by OUP – A Literary History of the Progressive Writer’s Movement in Urdu and two translations of Angarey, first published in 1932 only to be banned. ( Here is a link to the introduction by Snehal Shangvi of the Penguin Books India edition, an extract published in Scroll.in on 15 June 2014: http://scroll.in/article/666833/why-fundamentalists-got-this-urdu-book-banned-when-it-appeared-in-1932/ ) The writers associated with this movement were people who wrote not necessarily for the joy of crafting great literature; they wrote because they saw, and were quick to seize, the great inescapable link between literature and socio-political change. Literature for them was a valuable tool in the cause of nation-building and social transformation. ( Jalil, p. xx) With the publication of Angarey the definition of forward-looking underwent a sea-change and the epithets of irreligious, godless, sacrilegious, even blasphemous, came to be used for a radical, new sort of writing. Many of these writers ( and their readers) were conversant with Western literary styles and English-language authors. It is also important to remember that the glory days of the PWM also spanned the most tumultous period of modern Indian history — Gandhi’s call to Satyagraha, India’s response to the rise of fascism, Nehru’s Muslim mass contact programme, Gandhi’s second civil disobedience movement, the Second World War and its impact on India, the Bengal famine, the rise of Telengana, tebhaga, and other movements, Independence, Partition, and the communal disturbances that scarred the nation. ( Jalil, p. xxviii) Some of the ideas that need to be mentioned regularly are that though Urdu literature was not being written by Muslims along, the great majority of nineteenth-century Urdu writers were indeed Muslims.

This year has been marked by the publication of Rakhshanda Jalil’s thesis by OUP – A Literary History of the Progressive Writer’s Movement in Urdu and two translations of Angarey, first published in 1932 only to be banned. ( Here is a link to the introduction by Snehal Shangvi of the Penguin Books India edition, an extract published in Scroll.in on 15 June 2014: http://scroll.in/article/666833/why-fundamentalists-got-this-urdu-book-banned-when-it-appeared-in-1932/ ) The writers associated with this movement were people who wrote not necessarily for the joy of crafting great literature; they wrote because they saw, and were quick to seize, the great inescapable link between literature and socio-political change. Literature for them was a valuable tool in the cause of nation-building and social transformation. ( Jalil, p. xx) With the publication of Angarey the definition of forward-looking underwent a sea-change and the epithets of irreligious, godless, sacrilegious, even blasphemous, came to be used for a radical, new sort of writing. Many of these writers ( and their readers) were conversant with Western literary styles and English-language authors. It is also important to remember that the glory days of the PWM also spanned the most tumultous period of modern Indian history — Gandhi’s call to Satyagraha, India’s response to the rise of fascism, Nehru’s Muslim mass contact programme, Gandhi’s second civil disobedience movement, the Second World War and its impact on India, the Bengal famine, the rise of Telengana, tebhaga, and other movements, Independence, Partition, and the communal disturbances that scarred the nation. ( Jalil, p. xxviii) Some of the ideas that need to be mentioned regularly are that though Urdu literature was not being written by Muslims along, the great majority of nineteenth-century Urdu writers were indeed Muslims.

Here is a list of the major writers and poets associated with the Progressive Writers’ Movement ( as listed in Dr Jalil’s thesis, Annexure I)

Abdul Alim, Abdul Haq, Ahmad Nadeem Qasmi, Ahmed Ali, Akhtar Husain Raipuri, Akhtarul Iman, Ale Ahmad Suroor, Ali Sardar Jafri, Asrarul Haq Majaz ( his nephew is the poet and lyricist, Javed Akhtar), Ehtesham Husain, Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Fikr Taunsvi, Firaq Gorakhpuri, Hajra Begum, Hasrat Mohani, Hayatullah Ansari, Ibrahim Jalees, Ismat Chugtai, Jan Nisar Akhtar, Josh Maliabadi, K.M.Ashraf, Kaifi Azmi, Kanhaiyyalal Kapoor, Khawaja Ahmad Abbas, Krishan Chandar, Mahmuduzzafar Khan, Majnun Gorakhpuri, Majrooh Sultanpuri, Makhdoom Mohiuddin, Moin Ahsan Jazbi, Mulk Raj Anand, Mumtaz Husain, Mohammad Hasan, Niyaz Haider, Premchand, Qateel Shifai, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Rashid Jehan, Razia Sajjad Zaheer, Rifat Sarosh, Saadat Hasan Manto, Sagar Nizami, Sahir Ludhianvi, Sajjad Zaheer, Salam Machchlishahri, Sibte Hasan, Syed Muttalibi Faridabadi, Upnedranath Ashk, Wamiq Jaunpuri and Zaheer Kashmiri.

Both the translations published in April 2014 are readable. Fortunately these now exist and are readily available, a delightful  bouquet of riches for readers. Yet there is a vast difference in the quality of translations, and would be of valuable to interest to translators and academics. The notes on translations by Snehal Shangvi, Khalid Alvi and Vibha S. Chauhan are worth reading.

bouquet of riches for readers. Yet there is a vast difference in the quality of translations, and would be of valuable to interest to translators and academics. The notes on translations by Snehal Shangvi, Khalid Alvi and Vibha S. Chauhan are worth reading.

These are books that will be treasured and should find a place in every library, institution and be read by many.

The only question that I wonder about is how much were these writers influenced by the Irish literary movement of the early twentieth century?

Rakhshanda Jalil A Literary History of the Progressive Writer’s Movement in Urdu Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 2014. Hb. pp. 490. Rs. 1495

Angarey translated from the Urdu by Vibha S. Chauhan and Khalid Alvi. Rupa Publications, New Delhi, 2014. Pb. pp. 105. Rs. 195

Angaarey translated by Snehal Shangvi. Penguin Books India, New Delhi, 2014. Hb. pp. 170. Rs. 499

My monthly column, Literati, in the Hindu Literary Review was published online ( 31 May 2014) and in print ( 1 June 2014). Here is the url http://www.thehindu.com/books/literary-review/literati/article6069748.ece?textsize=small&test=2 . I am also c&p the text below.

My monthly column, Literati, in the Hindu Literary Review was published online ( 31 May 2014) and in print ( 1 June 2014). Here is the url http://www.thehindu.com/books/literary-review/literati/article6069748.ece?textsize=small&test=2 . I am also c&p the text below.

In translation

I am reading a terrific cluster of books — Rakhshanda Jalil’s A Literary History of the Progressive Writer’s Movement in Urdu (OUP); A Rebel and her Cause: The life of Dr Rashid Jahan, (Women Unlimited); and two simultaneous publications of the English translation of Angaarey — nine stories and a play put together in Urdu by Sajjad Zahir in 1932 (Rupa Publications and Penguin Books). Angaarey includes contributions by PWM members such as Ahmed Ali, Rashid Jahan and Mahmuduzzafar. As Nadira Babbar, Sajjad Zahir’s daughter says in her introduction to the Rupa edition: “The young group of writers of Angaarey challenged not just social orthodoxy but also traditional literary narratives and techniques. In an attempt to represent the individual mind and its struggle, they ushered in the narrative technique known as the stream of consciousness which was then new to the contemporary literary scene and continues to be significant in literature even today. …they saw art as a means of social reform.” She says that her father did not consider the writing of Angaarey and the subsequent problems they faced as any kind of hardship or sacrifice; rather “it provided them with the opportunity of expressing truths simply felt and clearly articulated.” It is curious that at a time when publishers worry about the future of the industry, there are two translations of the same book from two different publishers.

Translations are a way to discover a new socio-cultural and literary landscape. Last month, the English translation of Joel Dicker’s debut novel The Harry Quebert Affair (MacLehose Press), which has created one of the biggest stirs in publishing, was released. A gripping thriller, originally in French, it has sold over two million copies in other languages. A look at some other notable translations published recently:

Mikhail Shashkin’s disturbing but very readable Maidenhair (Open Letter), translated from Russian by Marian Schwartz, about asylum-seekers in Switzerland.

Juan Pablo Villalobos’s Quesadillas (And Other Stories) translated from Spanish by Rosalind Harvey is about 1980s Mexico.

Roberto Bolano’s The Insufferable Gaucho (Picador), a collection of short stories, translated from Spanish by Chris Andrews.

There is a range of European writers to be discovered in English translation on the Seagull Books list, Indian regional language writers from Sahitya Akademi, NBT, Penguin Books India, OUP, HarperCollins, Zubaan, Hachette, Navayana, Stree Samya, and Yatra Books.

Oxford University Press’s Indian Writing programme and the Oxford Novellas series are broader in their scope including works translated from Dogri and Konkani and looking at scripts from Bhili and Tulu.

Translations allow writers of the original language to be comfortable in their own idiom, socio-political milieu without carrying the baggage of other literary discourses. Translated literature is of interest to scholars for its cultural and literary value and, as Mini Krishnan, Series Editor, Oxford Novellas, writes, “the distinctive way they carry the memories and histories of those who use them”. Making the rich content available is what takes precedence. Within this context, debates about the ethics of publishing a translation such as J.R.R. Tolkien’s 1926 prose translation of Beowulf (HarperCollins), 88 years later, seem to be largely ignored though Tolkein described it as being “hardly to my liking”.

***

Linguistic maps available at http://www.muturzikin.com/ show the vast number of languages that exist apart from English. In the seven states of northeast of India alone there are 42 documented languages. Reports such as http://w3techs.com/technologies/overview/content_language/ all indicate that content languages (all though with strong literary traditions) such as Hindi, Marathi, Sanskrit, Punjabi and even Irish are used by less than one per cent of websites. Google India estimates that the next 300 million users from India won’t use English. It isn’t surprising then to discover that Google announced the acquisition of Word Lens, an app which can translate a number of different languages in real time. For now users can translate between English and Portuguese, German, Italian, French, Russian, and Spanish. Indian languages may be underrepresented on the Internet but, with digital media support and the rapid acceptance of unicode, an encoding which supports Indic fonts, translations will become easier. Soon apps such as Word Lens may expand to include other languages, probably even circumventing the need of publishers to translate texts.