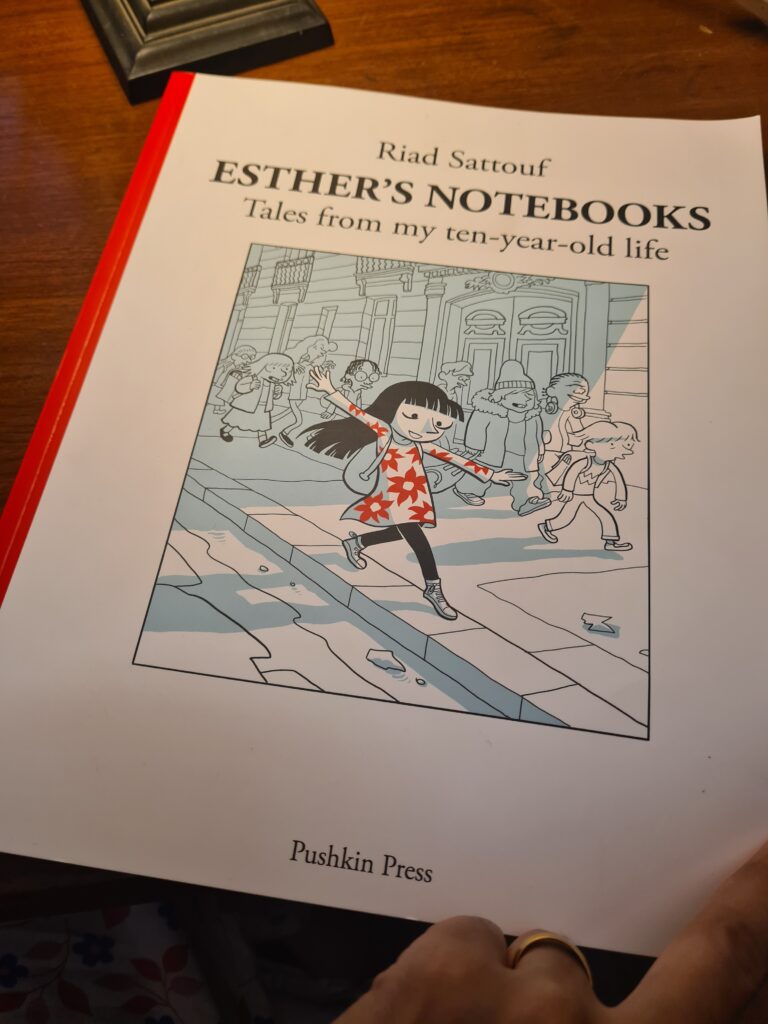

Riad Sattouf’s “Esther’s Notebooks: Tales from my ten-year-old life” , translated by Sam Taylor

Award-winning French cartoonist, graphic novelist, and film director of Franco-Syrian origin, Riad Sattouf’s cartoon strips revolving around a chatty little girl called Esther’s Notebooks have won him acclaim far and wide. Originally published in French, these cartoon strips were based on the cartoonist’s weekly conversations with the daughter of his friends. The stories revolve around the little girl’s day at school and the zillion questions that she has to ask of people around her. Every episode is short and told in first person. Sattouf began these cartoons in 2014-15. Subsequently, they were collected into five volumes. The first volume has now been translated from the French into English by Sam Taylor and published by Pushkin Press. An animation series based on the books has also been launched.

In the first volume, Esther’s Notebooks: Tales from my ten-year-old life, Sattouf captures the child-like sentence constructs beautifully. He also manages to capture the wide-eyed wonder of children about the world around them and their propensity for asking the most uncomfortable questions. The language used in the cartoon strips is abrupt, at times lacks prepositions, but is pitch perfect as regards a ten-year-old’s speech. It is impossible to tell if this is a characteristic of the English translation or was it like this in the original English. The stories capture the child’s growing awareness of her environment including cultural details. Each cartoon strip is a chapter in the book and has a descriptive title exactly as children would introduce a story — relying upon the core words and no more. For instance, “Gunfire”, “Mums and Dads”, “The Charlie”, “The Gym”, “Breasts” and so on. A range of topics are covered in the stories. These range from racism ( Rebeus and Renois), religion, politics, separated families, grief, social divisions, gaming addiction, pornography etc. It is curious and yet it is perfect as to how many of the strips are set in the playground. It is true that children acquire much of their “knowledge” through their peers and through play. But in this book it works beautifully as the playground offers the lanscape for maximum number of stories and scenarios to swirl around the protagonist. The deadpan delivery of the little girl while narrating incidents is extraordinarily well done. It is almost as if the cartoonist is channeling the little girl and presenting to the readers her descriptions as is. The biggest gift that Sattouf bestows upon this form of storytelling is that he conveys without judgement all that the little girl tells him including the confused sidestepping of her teacher with regard to the Hundred Years War.

Esther’s Notebooks lays bare how much the children are acutely aware of or know about. Sometimes out of sheer ignorance and innocence they mouth words, behaviour and attitudes. But the dumbing down of children or shutting them down completely as the teacher did when asked but the Hundred Years War or when the little girl asks very loudly at the family dinner table about the website “Youpaurne” ( she had overheard referenecs to “youporn” in school), her family can only sputter in embarassment. It is probably an age-old tactic to shut kids down in this manner or choose to ignore them but in today’s day and age, it is a dangerous precedence to set of misinformation. More so as kids of today have multiple ways of accessing information. Apart from of course not recognising the child as an individual in their own right. It does not matter if they are young in years. They are bright eyed and bushy tailed, eager to make sense of this crazy world. This is where the talent of Sattouf lies to convey as precisely and unfiltered as possible what the little girl utters.

The popularity of these comic strips in French and now in English are a testament to how kids want their reality reflected. Adult readers of these comic strips also enjoy the sharpness with which the stories are told, not mincing words on various issues. Perhaps Sattouf’s stint as a cartoonist for the French satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo helped polish his skills at storytelling. The child may speak innocently or out of sheer ignorance but the rapidity with which the adult storyteller hones in upon precisely those scenarios that may startle adult readers comes with years of practice. Otherwise it is impossible to pick out that which is necessary from the conversaton that children make as they tend to prattle on endlessly.

Esther’s Notebooks ( Vol 1) is utterly fantastic. It is worth buying and spreading the joy with others too.

22 July 2021