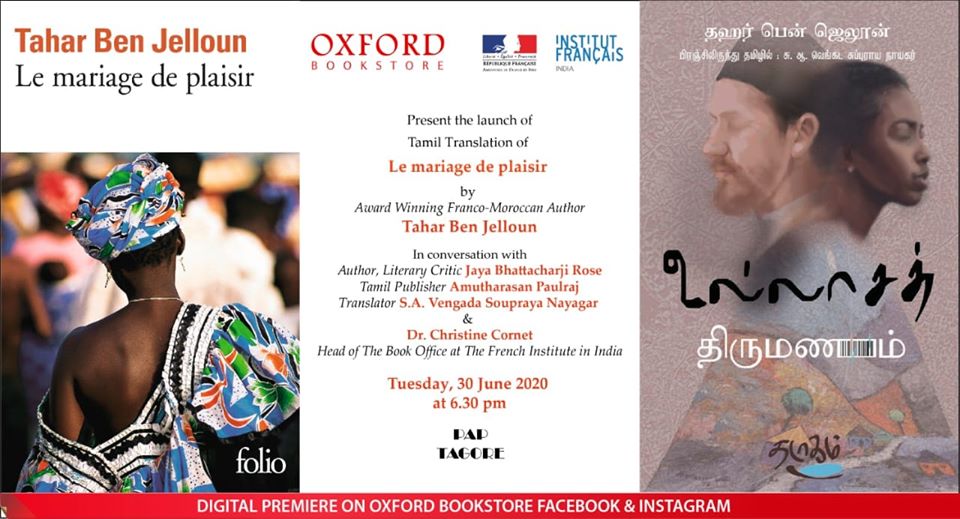

In conversation with Tahar Ben Jelloun

On 30 June 2020, I was in conversation with the eminent and award-winning Franco-Moroccon author, Tahar Ben Jelloun. It was to celebrate the launch of Tamil translation of Le mariage de plaisir ( A Marriage of Pleasure). The book has been translated by S. A. Vengada Soupraya Nayagar and published by Thadagam Publications. Dr Christine Cornet, French Book Office, was the moderator. The digital book launch was organised by Oxford Bookstore and French Institute in India.

This was a unique experience. I had the privilege of participating in a book launch which involved three languages — English, French and Tamil. Tahar Ben Jelloun comes across as a gentleman who is a deep thinker and an “activist” with words. Reading him is a transformative experience. Something shifts within one internally. It was memorable!

To prepare for the launch, Dr Cornet and I exchanged a few emails with the author. Tahar Ben Jelloun is fluent in French but has a tenuous hold over English. Hence he prefers to communicate in French. Whereas I am only fluent in English. Dr Cornet is profficient is bilingual. All of us were determined to have a smooth digital book launch with minimal disruptions as far as possible. Tough call! So we decided that I would send across a few questions to the author to answer. Given that the Covid19 lockdown was on, it was impossible to get the English translations of the author’s books. Fortunately, I found ebooks that coudl be read on the Kindle. Thank heavens for digital formats! I read the novel and then drafted my questions in English. These were then translated into French by the French Institute of India. This document was forwarded via email to Tahar Ben Jelloun in Paris. He spent a few days working on the replies. Once the answers were received, these were translated into English for my benefit. It was eventually decided that given the timeframe, perhaps it would be best if we focused on only five questions for the book launch. So we went “prepared” for the launch but only to a certain degree. While we were recording the programme, something magical occurred and we discussed more than the selected five questions. In fact, at a point, Tahar Ben Jelloun very graciously opted to reply in English. We discovered not only our mutual love for Mozart and Jazz musicians such as Ella Fitzgerald, John Coltrane etc but that we play their music in the background while immersed deeply in our creative pursuits — painting and writing. Coincidentally the conversation was recorded on Ella Fitzgerald’s death anniversary, 17 June. How perfect is that?!

Born 1944 in Fez, Morocco, Tahar Ben Jelloun is an award-winning and internationally bestselling novelist, essayist, critic and poet. Regularly shortlisted for the Nobel Prize in Literature, he has won the Prix Goncourt and the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award. His work has also been shortlisted for the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize. He received the rank of Officier de la Légion d’honneur in 2008. Some of his works in English translation include About My Mother (Telegram), The Happy Marriage, This Blinding Absence of Light, The Sand Child and Racism Explained to My Daughter. He won the Goncourt Prize in 1987 for La Nuit sacrée. His most recent works published by Éditions Gallimard include Le Mariage de plaisir (2016) and La Punition (2018).

Q1. Why and when did you decide to become a writer? Did the internment at the age of 18 years old have anything to do with your decision?

When I was a child, I didn’t dream of being a writer, but a filmmaker. At the same time, I wrote short stories, I illustrated them with drawings.

When I was sent to an army disciplinary camp in July 1966, I never thought I would get out. Everything was done to mistreat us and it gave us no hope of liberation. So, I clandestinely started writing poems with lots of metaphors so I wouldn’t be punished in case they were found. Nineteen months later, in January 1968, I was released and I had little papers in my pocket on which I had written poems. It was the poet Abdelatif Laabi who published them in the magazine Souffles that he had just created with some friends. He himself was thrown in jail a few years later, where stayed for 8 years!

This was my debut as a writer.

Q2. You learned classical Arabic while learning the Quran by heart and yet you choose to write books in French. Why?

Yes, I learned the Quran without understanding it. But my father changed my birth date so that I could join my older brother at the bilingual Franco-Moroccan school. That’s where I learned the French language and I started reading a lot of the classics and also a few novels of the time like The Stranger by Camus, The Words by Sartre or Froth on the Daydream by Boris Vian. But I preferred poetry above all else.

Q3. Your books have been translated into multiple languages. At last count it was 43. Now Tamil too. Is your writing sensibility affected knowing that readers across cultures will be reading your books? Or it does not matter?

For a writer, being translated consolidates his legitimacy as a writer, he is recognized, it helps him to continue; to be more demanding with himself. It’s a source of pride, but you can’t rest on your laurels, you have to work, you have to pursue your writing with rigor. For me, each translated book is a victory against the current trend of young people reading less literature. It is true that they are solicited by easier and more attractive things.

Translation is a gift of friendship from an unknown language and culture. I am happy today to be read in Tamil, just as I was happy to be read by blind people thanks to an edition in Braille, just as I was happy and surprised to be translated into Esperanto, that language which is meant to be universal, but which remains limited to some 2000 readers.

Q4. Your preoccupation with the status of women is a recurring theme in your literature. Why? The two points of view presented by Foulane and Amina about their marriage is extraordinary. At one level it is the depiction of a marriage but it is incredible art, almost like a dance in slow motion. Did you write The Happy Marriage in reaction to the Moudawana law passed in Morocco? If so, what was the reaction to the novel in Morocco?

For me, as an observant child, everything started from the condition of the women in my family, my mother, my sister, my aunts, my cousins, etc., and then went on to the condition of the women in my family. I could not understand why the law ignored them, why one of my uncles had two wives officially and why both women accepted this situation. From childhood, I was interested in the status of women. Later, I had to fight for my mother to be treated better by my father, who didn’t see any harm in her staying at home to cook and clean. Then I discovered that it is all women in the Arab and Muslim world who live in unacceptable conditions. Wrestling has become essential for me. My first novel Harrouda is inspired by my mother and then by an old woman, a prostitute who came to beg in our neighborhood. It is a novel that denounced this condition of women not in a political and militant way, but with literature, with writing. The novel then became stronger than a social science essay. This struggle is not over. Things have changed in Morocco today; the Moudawana, that is to say the family code has changed, it has given some rights to women, but that is not enough. This change is due to the will of King Mohammed VI, a modern and progressive man.

In Morocco, people don’t read much. I never know how my books are received. In general, I tour high schools and universities and try to encourage young people to read. Let’s say my books are circulating, but illiteracy is a tragedy in Morocco where more than 35% of people cannot read and write, especially people from the countryside.

Q5. Have you tried to replicate the structure of Mozart’s Concerto for piano and orchestra No. 16 in D major, K 451? I read somewhere that you liked the composition very much. I felt that there were many similarities in your form for The Happy Marriage and K451. Something about the predictable opening of the story/concerto which develops smoothly, almost intoxicating, and then the last movement, a complete surprise, a triumph. Was this intentional? ( Aside: Here is a recording that you may have already heard. I play it often while working. Barenboim & Argerich : Mozart Sonata for Two Pianos, K.448)

This similarity comes as a surprise to me. I love Mozart’s music, which I listen to a lot. But I never associated his music to this novel. I’m also a big jazz fan. I listen to jazz when I paint, but I need silence when I write. In any case, thank you for pointing out this link, which makes me proud.

Q6. Do you think fiction is a more powerful tool to communicate with readers about commenting upon society and suggesting reform rather than a straightforward narrative non-fiction?

Yes, fiction has a more effective power for information or statistics. During the confinement here in Paris, it was Albert Camus’ The Plague that was most commissioned and read. TV was overwhelming us with often contradictory information. A novel allows the reader to identify with the main character. Literature and especially poetry will save the world. In the long term, especially in these times when cruel, stupid and inhuman leaders rule in many countries. Against their violence, against their vulgarity, we oppose poetry, music, art in general.

Q7. Do you think the function of an artist is to be provocative?

An artist is not a petit bourgeois in his slippers. An artist is an agitator, an impediment to letting mediocrity and vulgarity spread. Some people make a system out of provocation, I am for provocation that awakens consciences, but not all the time in provocation. It is necessary to go beyond and to create, to give to see and to love. You don’t need to be sorted, but you don’t need to be provocative either. Beauty is a formidable weapon. Look at a painting by Turner or Picasso, Goya or Rembrandt, there is such strength, such beauty, that the man who looks at it comes out of it changed by so much emotion. Look at Giacometti’s sculptures, they’re enough on their own, no need for a sociological discourse on human distress, on stripping.

Q8. As a writer who has won many prestigious awards, what is it that you seek in promising young writers while judging their oeuvre for The Prix Goncourt?

When I read the novels submitted for the Prix Goncourt, I look for a writing style above all, a style, a universe, an originality. That’s very rare. It’s always hard to find a great writer. You look, you read, and sometimes you get a surprise, an astonishment. And there, you get joy.

Q9. You are a remarkable educator wherein you are able to address children and adolescents about racism and terrorism: India is a young country, today what subject animates you and what message would you like to convey to Indian youth?

The subjects that motivate me revolve around the human condition, around the abandoned, around injustice. There is no literature that is kind, gentle and without drama; Happiness has no use for literature, but as Jean Genet said “behind every work there is a drama”. Literature disturbs, challenges certaines, clichés, prejudices. It makes a mess of a petty, hopeless order.

To Indian youth, I say, don’t be seduced by appearance, by the fascination of social networks, by addiction to objects that reduce your will power and endanger your intelligence. We must use these means but not become slaves to them. To do this, read, read, read and read.

Q10. You are one of the most translated contemporary French-language authors in the world. In India, French is the second most taught foreign language, what is the future for the Francophonie?

France has long since abandoned the struggle for the Francophonie. The Presidents of the republic talk about it, at the same time they lower subsidies of the French institutes in the world. Today, French is defended by “foreigners”, by Africans, by Arabs, by lovers of this language all over the world. France does little or nothing to keep its language alive and lets English take more and more space.

Q11. What next?

What more can I say? Poetry will save the world. Beauty will save the world. Audacity, creation, art in all its forms will give back to humanity its soul and its strength.

Here is the video recording of the session:

4 July 2020