‘That is not how friendships work and that is not how you win people. You can’t win with authority or dictatorship. You don’t want to be feared; you want to be loved and being loved is so much more a happier feeling than fear.’

‘That is not how friendships work and that is not how you win people. You can’t win with authority or dictatorship. You don’t want to be feared; you want to be loved and being loved is so much more a happier feeling than fear.’

That day I learnt one of the most important lessons of my life: my father’s weapons may have been guns and ammunition, but my weapons had to be peace. Always.

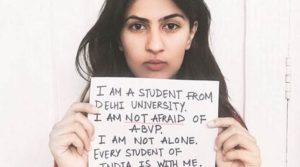

Gurmehar Kaur, an undergraduate student at University of Delhi, “shot to fame” when she started a  protest against the ruling nationalist party Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) student wing, Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), who had behaved violently and disrupted a seminar being held at Ramjas College [in February 2017]. She posted a picture of herself on a social media site holding up a placard that read: “I am a student of Delhi University. I am not afraid of the ABVP. I am not alone. Every student of India is with me.”’ ( #studentsagainstABVP ) Overnight this petite, poised and soft-spoken student became the face of the student protests. Being the daughter of an Army officer who had been killed in the Kargil war when she was a toddler and speaking of peace was completely unacceptable to the fundamentalists. It unleashed a series of horrific abuse directed at this young girl. She was threatened with rape, she was trolled, right wing sympathisers mocked her and she was even compared to the most wanted terrorist in India, Dawood Ibrahim. All this was completely uncalled for but was in keeping with the nationalist fervour espoused by the “nationalists”. ( Scroll, 7 Feb 2018, “The abuse of soldier’s daughter Gurmehar Kaur shows that Savarkarite nationalism is on the rise” )

protest against the ruling nationalist party Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) student wing, Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), who had behaved violently and disrupted a seminar being held at Ramjas College [in February 2017]. She posted a picture of herself on a social media site holding up a placard that read: “I am a student of Delhi University. I am not afraid of the ABVP. I am not alone. Every student of India is with me.”’ ( #studentsagainstABVP ) Overnight this petite, poised and soft-spoken student became the face of the student protests. Being the daughter of an Army officer who had been killed in the Kargil war when she was a toddler and speaking of peace was completely unacceptable to the fundamentalists. It unleashed a series of horrific abuse directed at this young girl. She was threatened with rape, she was trolled, right wing sympathisers mocked her and she was even compared to the most wanted terrorist in India, Dawood Ibrahim. All this was completely uncalled for but was in keeping with the nationalist fervour espoused by the “nationalists”. ( Scroll, 7 Feb 2018, “The abuse of soldier’s daughter Gurmehar Kaur shows that Savarkarite nationalism is on the rise” )

Gurmehar Kaur dropped out of the Ramjas student protest campaign but her inherent belief in peace building measures is the best way forward in such adverse times, divided opinion. Many commended Gurmehar Kaur for speaking wisely while many others bayed for her blood. It did not deter her and she continues to promote free speech. So much so that in October 2017, TIME magazine featured her in their list of next generation of leaders 2017. She was called a “free speech warrior”. Probably given the worldwide sensation she had become Gurmehar Kaur was offered a book contract by Penguin Random House India to write her story.

Small Acts of Freedom was published recently. It is a slim memoir. Although in her introduction to the book she recounts her involvement in the Ramjas college protests but chooses not to mention it at all in later chapters. Instead she prefers to dwell upon the incidents preceding the incident. Her life as that of a two-year-old girl and a younger sister brought up by a widowed mother and a maternal grandmother. How desperately they miss their father/husband but their mother ensures his memory is kept alive. It is a well-written account by a young woman who has been catapulted into the limelight and has had to learn to mature rapidly as an adult. Yet the simple language used and at times the wide-eyed wonder about her memories such as that of her grandmother hiding the chocolates indicates how close she is still in years to her childhood. She grew up in Punjab, a state which had been worst affected by the violence of Partition in 1947, and whose repurcussions were being felt decades later. In the 1990s Punjab was terribly affected by the separatist Khalistan movement and it had disrupted civil society considerably. Violence was all around. It was in this atmosphere that Gurmehar spent her childhood, listening to vicious talk of the adults spewing hatred particularly towards Pakistan, when it was her father who had been martyred in the war against Pakistanis and he was the one who had inculcated in his daughter the love for peace.

Gurmehar Kaur lacks the perspective ( which comes with age and experience) and tools of academic discourse to dissect and analyse why she did what she did in February 2017 but her firm resolve to do what is best as her upbringing has taught her is what shines through in Small Acts of Freedom. The curious structure of the text with its shifting points of view is very smartly done. To capture these shifts in voices and different tenses is either a class act by a master craftsman or it is simply who she is, wanting to accommodate the important women in her life. The chapters too alternate between different decades — her mother’s childhood and marriage in ’70s and ’80s– to what Gurmehar remembers of her life in late ’90s. Laying down in words a narrative which is so complicated like this while allowing it to flow seamlessly is an astounding feat in one so young. At times it seems as if the story is moving chronologically when it is suddenly disrupted seemingly while the main narrative goes off at a tangent — much as if this tale is being narrated orally with tiny stories embedded within it.

All said and done it is a readable book highlighting what Gurmehar Kaur has learned at home as well as learned to overcome slights at her expense. It is a timely book since Gurmehar Kaur is perceived as the face of student protests in Delhi but she is also an icon for the youth, a messenger of peace and hope.

Read it.

Gurmehar Kaur Small Acts of Freedom Penguin Books, India, 2018. Pb. pp. 200 Rs. 299

7 February 2018

(Dr Shobhana Bhattacharji retired as professor of English Literature from Delhi University a few years ago. Her doctorate is in Lord Byron’s drama. She is fluent in English and Hindi. She reviewed Krishna Baldev Vaid’s novels when they were first published by Penguin India in the 1990s. Now the books have been rejacketed and reissued. Here is her review with a short introductory note.)

(Dr Shobhana Bhattacharji retired as professor of English Literature from Delhi University a few years ago. Her doctorate is in Lord Byron’s drama. She is fluent in English and Hindi. She reviewed Krishna Baldev Vaid’s novels when they were first published by Penguin India in the 1990s. Now the books have been rejacketed and reissued. Here is her review with a short introductory note.)

The translations of Krishna Baldev Vaid‘s two autobiographical novels were so different to each other that I read the Hindi versions to see whether the difference was in the originals. Till then, I had not read the original of a translated work I had to review on the principle that a translation is meant for a target audience and I tried to read it like an ideal target reader. Reading these novels in Hindi, however, taught me how much a translator, even if the translator is the author himself, can alter a novel. The Hindi title of Steps in Darkness is Uska Bachpan. The title of the second novel in Hindi, written 25 years later, was Guzra Hua Zamaana, which was also a famous Madhubala/Lata film song from the sad love story Shirin Farhad, filmed in 1956. It is Shirin’s final goodbye to her beloved Farhad as her ‘doli’ (bridal conveyance) leaves for her husband’s home. She begs Farhad not to accuse her of infidelity; her marriage to another man was not of her making. Vaid‘s novel is a searing farewell to his beloved pre-Partition India.

These two novels, written a quarter of a century apart, centre around Beero, who lives in a small town in undivided Punjab. In the first novel, confused by the adult world, and suffocated by the poverty of his home, Beero is young enough to enjoy snuggling in his grandmother’s lap. His parents are embarrassed to beg the shopkeeper for goods they cannot pay for, so they send Beero, whose dignity is lacerated by this as it is by his torn shorts and having to fetch his father from the gambling den. He escapes into his dreams. The filth and stink of their slum assail the reader but Beero entertains himself with a hornets’ nest in the drain. He dreams of tying some hornets together by their legs and making a kite for himself. None of his dreams is fulfilled. There is no money to buy or make kites. His happiness in his grandmother’s stinking lap is free, but is taken away because his mother hates it.

His friends unwittingly remind him of his unhappiness. Aslam, for instance, has a happy home and a beautiful married sister, Hafeeza, whom Beero gets a crush on. Beero’s mother hates “Muslas” and warns her son against them, but Beero eats at Aslam’s home and becomes “half a Muslim,” as he says in the second novel in which he also recites the kalma. Beero’s own home is riven with misery. The parents have terrible fights over money, the father’s drinking, gambling, and friendship with a sardar, called “Miser” by Beero’s mother who suspects her husband–rightly, as it turns out in the second book–of sleeping with the Miser’s beautiful wife. The mother spits venom and turns everything into tense misery. Her rages dominate Beero’s life but not his understanding. There is a searing passage where a bored Beero, who wants to hear about kings and princesses, listens to what he considers his mother’s complicated repetitious story of her early married life:

O, it was hell. Your Granny used to starve me for days on end. She used to lock me up in the lumber-room; I wonder I didn’t die of fear. No one ever cared for me. Neglected, I used to cry all by myself all the twenty-four hours. Your father was even then addicted to loafing. He never came home from school. Your Granny is to blame for spoiling him. She was always reproachful toward me because I had no sense. What sense could I have at that age?. . . Girls of my age were still playing hide-and-seek in the lanes while I had to wash mounds of clothes. In winter my tiny hands were always numb. I had fever every night; my bones used to ache; and all I had to sleep in was a worn-out blanket. Oh, the long dark frightful winter nights I spent shivering and crying, silently, for at the slightest sound your Granny would get up and start cursing the day she married her son to me. . . .Very often just as I lay down late at night after a day’s drudgery I would be commanded to press your Granny’s legs. While doing that if I happened to doze off I was kicked and beaten. (49-50).

Stories weave a complex pattern through the novel. There is, for instance, the richly ironic echo of the Ramayan in Beero’s mother’s name, Janaki. Beero’s love for fairy stories is soon replaced with fantasies of a fight-free home. Once he actually makes a fantasy come true. Anticipating a storm if his mother comes out of the kitchen and sees a hated neighbour talking to Devi, Beero’s sister, he efficiently lies to both parties of the potential war and gets the neighbour out of the house. Beero has two aims: to comprehend the world and to make it a less anxious place. When the domestic violence gets out of hand, he tries to die, but even that escape is not permitted. We leave him looking into a mirror which he has broken.

The wonder of Steps in Darkness lies in its graceful intermingling of the child’s confusion with solid details of the place, its people and their relationships. Its power is in its language. When one responds in two languages to a book, one wonders how much of Tolstoy and others one has missed. Some translation, of course, is better than none, and some translations are better than others. In this one, for instance, the curses, especially the vivid “progeny of swine” or “progeny of a dog,” require less than a second to translate back into the original and with it come stomach-knotting memories of school in Punjab where either curse would result in furious battles. Because of such violent consequences, “kutte ka bachcha” means much more–at least, it did forty years ago–as an insult than “son of a bitch,” and one is grateful that the author did not use “son of a bitch” in his translation. There are few glitches. For instance, “loaves” for “chapatis” doesn’t work. “Loaves” would probably remind most middle-class readers of Britannia bread. For readers unfamiliar with chapatis, to speak of two or three loaves per person, even among the well off, would be unbelievable.

On the whole, however, the translation has a cultural flavour that the second book does not. Its English is smoother, less defamiliarized, but sometimes, as in “soul” of a singer’s voice (27), one is uncertain what the original might have been. (It is “soz”.) Occasionally, the translation illuminates both versions, e.g. “gorilla” for “pehlwan.” Of course, not every reader will respond in two or, as these books require, three languages, but one misses the immediacy of Steps in Darkness.

There is a lot of mysteriousness in the novel. Why do Devi and her father weep at the end of the novel? What is Naresh’s relationship with his “mother”? Why is Aslam withdrawn after his sister leaves for Lahore? Some of the incomprehensibility is consistent with the child’s steps in darkness, but there should have been some way of making the reader know more than Beero.

The wonderful preface of Guzara Hua Zamana has been dropped in The Broken Mirror. In it, the character Beero talks of how the writer created an incomplete Beero in the first novel and then tried to flesh him out in later stories. Twenty-five years later, Beero tells him that he cannot escape another novel about Beero and that if the novelist is going to drag his feet over it, Beero himself will write it. At this point, he says, he fainted and when he recovered, the novel had been written.

In this first person narrative, Beero tries to piece together the images split by the shattered mirror of the end of the previous story but gives up the attempt because, as he says in passing, the partial stories he had written were lost in the Partition riots. The Broken Mirror is composed of his different worlds–Lanes, Bazaar, Lahore, and Borderlands. The English version does not have Beero’s caustic critique of the first novel. Other minor details that have been dropped also take away from a richness that Guzara Hua Zamana has. For instance, Allah Ditta’s incompetence is wonderfully conveyed in the casual comment that he must have murdered some Iranian doctor, stolen his degree, and set up practice here. No one believes this, of course, but the remark has a vigorous and delighted inventiveness which is characteristic of much Punjabi speech (and Bombay filmi dialogue).

Still, The Broken Mirror resolves much of the mysteriousness of Steps in Darkness. Although the publication details in this edition wrongly suggest that it was written nineteen years after Steps in Darkness, the style bears out that it is more than a sequel. The hesitation of the earlier novel which may have been the child’s as well as the author’s, and which resulted in withholding information from the reader, is replaced with a crisp narration of details. The powerful story of Beero’s adolescence and the unlooked for political freedom which incarcerates them in fear and Bakka’s barn does not need stylistic fancy footwork to impress the reader.

The most powerful aspect of The Broken Mirror is the building up of events towards Partition. Initially, the idea of separation remains in the background. Muslim, Sikh and Hindu friends hang out together. Then Aslam notices that the two Sikhs in their group have begun to talk strangely and advises Beero to be circumspect before them. Language and humour are the first casualties of this growing monster of hatred. Occasionally people mention the possibility of Pakistan. Then, with a mere change of tense, they talk of “when the riot occurs,” and Hindus begin to send their belongings to the “other” side. Finally, Pakistan is a reality. Communal positions harden, bewildering Beero even more than the adult world did in Steps in Darkness. In a magnificent few pages, Krishna Baldev Vaid narrates the activity of a Peace Committee meeting which has been called by the marginalized of the town: a Congress man, Keshav, In-Other-Words, and an aging prostitute who says she is like Gandhi because she does not discriminate against any community in her work. The unpredictable swings from hostility to brotherhood and back again are terrifying because they defy rationality, and because we have seen them again in the run-up to and aftermath of the breaking of the Babri Masjid. Then come the engulfing madness and killings of 1947.

Hiding in Bakka’s barn, Beero’s mind is a spate of words. Narrative breaks down just as everything else has. He struggles to understand events and himself. All he knows is that he lacks Keshav’s courage to die for a cause, and that he cannot kill anyone or blame any one side for being the prime mover of the violence. Eventually, in tearless bewilderment and with heads down, they go to the makeshift refugee camp in the school. There, beside an abandoned, bloodied baby girl, Beero finally cries.

With a book that achieves the nearly impossible business of hiding its craftsmanship, there is little one can do except break the unwritten code for reviewers and tell the story. But no retelling can capture the delicacy, intricacy, and strength of this extremely moving novel.

Krishna Baldev Vaid Steps in Darkness (trans. from Hindi by the author); The Broken Mirror (trans. from Hindi by Charles Sparrows in collaboration with the author) New Delhi: Penguin India, rpt 2017, 1995 (first publd. New York, 1962); New Delhi: Penguin, rpt 2017, 1994 (first publd. In Hindi, 1981)

14 June 2017

‘It really is a pathetic thing. To mourn a past you never had. Don’t you think?’

‘It really is a pathetic thing. To mourn a past you never had. Don’t you think?’

p.216

Sunjeev Sahota’s The Year of the Runaways is his second novel. According to Granta in 2014, he was one of the promising writers from Britain. I have liked his writing ever since I reviewed his debut novel, Ours are the Streets, for DNA in 2011. The first chapter of The Year of the Runaways was extracted in Granta, Best of British novelists. It is about a few men from India who choose to migrate to the UK. They are from different socio-economic classes. Tochi is a chamar, an “untouchable”, from Bihar who had gone to Punjab in search of a job, but with his father falling ill, returned to the village. Unfortunately during the massacres perpetrated by the upper castes his family was destroyed too. So he gathered his life-savings and left India. The other men who leave around the same time are Avtar and Randeep, migrants from Punjab. Randeep is from a “better” social class since his father is a government officer and he is able to migrate using the “visa-wife” route. But when these young men get to Britain, they are “equal”. It is immaterial whether they are working as bonded labour or on construction sites or cooking or even cleaning drains. They are willing to do any task as long as it allows them to stay on in the country. Apparently living a life of uncertainty and in constant fear of raids by the immigration officers is far preferable to life at home.

The women characters of Narinder, Baba Jeet Kaur and Savraj are annoying. Maybe they are meant to be. Given how much effort and time has been spent figuring out the male characters, the women come across as flat characters. Narinder, Randeep’s visa-wife, seems to have the maximum social mobility in society as well as amongst these migrants but she remains a mystery. It is only towards the end of the novel that just as she begins to find her voice and asserts herself, the story comes to an abrupt end.

I like Sunjeev Sahota’s writing for the language and sensual descriptions. He makes visible what usually lurks in the shadows, confined to the margins. He makes it come alive. It is remarkable to see the lengths a storyteller can go to tell a story that has a visceral reaction in the reader. Also it is admirable that while living in Leeds, UK, Sunjeev Sahota has written a powerful example of South Asian fiction that is set in Britain without ever really showing a white except for the old man Randeep had befriended while working at the call centre. Sunjeev Sahota admires Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children. ( It was also the first novel he read as he admits in the YouTube interview on Granta’s channel.) Rushdie too has given a glowing endorsement to The Year of the Runaways saying, “All you can do is surrender, happily, to its power”. ( http://granta.com/Salman-Rushdie-on-Sunjeev-Sahota/) True. The only way to read this novel is to surrender to it. But has Sunjeev Sahota broken new ground as his literary idol, Rushdie did with his award-winning novel? The purpose of literary fiction is to make the reader unsettled rather than just hold a mirror up to the reality. As a tiny insight into the hardships economic migrants experience this novel is astounding. But it falls short of being thought-provoking and disturbing or breaking new ground in literary fiction. I doubt it.

Sunjeev Sahota’s gaze on India is an example of poverty porn in literature. He has got the migration patterns, the hostility at ground level in Bihar and Punjab and the nasty descriptions of the Ranvir Sena or the Maheshwar Sena as they are referred to in the novel accurately. ( I think the novel alludes to these massacres as described in this wonderful article by G. Sampath in the Hindu, published on 22 August 2015 http://www.thehindu.com/sunday-anchor/sunday-anchor-g-sampaths-article-on-children-of-a-different-law/article7569719.ece ) Disappointingly Sunjev Sahota’s voice is clunky at times and comes across as well-researched but a trifle jagged in the Indian parts. The British bits are brilliant as if to the Manor born, which Sunjeev Sahota is! Much is explained by what he hopes to explore in this novel in an interview he gave Granta ( https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=65mtLCbODCk : 23 April 2013) :

What does it mean being unmoored from your homeland and what does that do to a person and subsequent generations? What happens to that hold that is created? What fills it? Then where does one go from there?

This is a strong and fresh voice. Sunjeev Sahota must be read even if this novel ends with a bit of a convenient ending. This is an author whose trajectory in contemporary literature will be worth mapping.

The Year of the Runaway is wholly deserving to be on the ManBooker longlist 2015 but I will be pleasantly surprised to see it on the shortlist.

Sunjeev Sahota The Year of the Runaways Picador India, Pan Macmillan India, New Delhi, 2015. Hb. pp. 480 Rs 599

27 August 2015

Well known artist Orijit Sen’s mural of life in Punjab is awe-inspiring. The digital mural, arranged almost like a street-view map, spans across two walls. Every inch of it is covered with people, buildings, fields of rice and wheat, roads, shops, houses, trees, water bodies, even temples as he tries to capture the social fabric of the state.

The mural was originally made for the Virasat-e-Khalsa, a multi-media museum and cultural centre in Anandpur Sahib and took a few years to complete.

Through the mural, the artist wishes to capture the indomitable spirit of the Punjabis as they face and live through the changes that their lives have gone through over the years as dams were built over rivers, fields replaced forests and globalisation began to creep in.”

An article in the Hindu about it ( 19 April 2012):

And writer, Amandeep Sandhu’s reply to this post, when I put it up on my facebook page ( 29 May 2013)

“Thanks Jaya. I was at Anandpur Sahib last summer and had the opportunity to see Orijit and team’s work. The mural is excellent, its attention to detail is superb. It is an brilliant socio-anthropological work of art. Respect! My problem with the museum is a) the maintenance of Orijit’s work, b) that the sections of the museum which talk about the Sikh Gurus (after Orijit’s sections) posit that the real history of Punjab starts with the birth of Guru Nanak and pay only a brief lip service to the period of the Harrapan-Mohenjodaro Indus valley civilization, the Vedas, the 5000 year rich cultural history of the land. One can understand that the museum is Virasat-e-Khalsa, the culture of the Khalsa, but given how hundreds of visitors come to the museum each day it is an opportunity missed in providing a composite, holistic view of society.”

Orijit Sen replied to Amandeep Sandhu on 29 May 2013

“Amandeep, your comments are very perceptive. Its true that a splendid opportunity to celebrate the amazingly rich history of the region has been compromised for short sighted political reasons. I wish it could have been done differently.”

Uploaded on 29 May 2013, Orijit Sen’s comments added on 30 May 2013.

Another memoir by an ex-civil servant. An account of thirty-six years of service in the Bengal and Punjab cadre, but mostly focused on events in Punjab. A memoir like this is useful to read since it records socio-historical and economic events that tend to be easily forgotten — at least in public memory. But to wade through this book you will have to ignore the “I, me. myself” tone that does get a tad annoying. In the introduction Robin Gupta says “I should confess at this stage that I have, in these memoirs, permitted myself an element of the writer’s licence to interpret and depict places, individuals and happenings.” Then he should have called it “bio-fic”, a term coined by David Lodge.

In his endorsement of the book, Khushwant Singh says, ” Robin Gupta …memoirs mirror the chiaroscuro of contemporary India as observed by a civil servant…[This book] is a literary milestone.” But in his recently published Khushwantanama says “it is tempting to write one’s life experiences. A first novel is very often autobiographical. However, non-fiction is a different ball game altogether. Memoirs of retired generals and civil servants rarely make for good reading. …What is permissible in a biography is not suitable for an autobiography.”

26 April 2013

Robin Gupta And what remains in the end: The memoirs of an unrepentant civil servant Rupa Publications India Pvt.Ltd. Pb. pp. 290. Rs. 350