“The Revolutionary Life of Freda Bedi” by Vicki Mackenzie

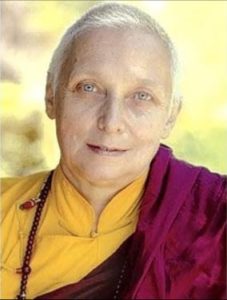

The Revolutionary Life of Freda Bedi by Vicki Mackenzie is an account of an extraordinary Derby-born woman Freda Houlston. Born in 1911, educated at Oxford and married in 1933 to Baba Bedi bringing her to India at the height of the freedom struggle for Independence. She met her husband during the local meetings of the Majlis, the Indian students’ society, and listened to debates about Gandhi and India’s quest for freedom. According to Andrew Whitehead ( who too is working on a biography of Freda Bedi ; Derby Telegraph & The Wire ) “she went to the more tumultuous October Club, where left-wing students gathered to oppose fascism and cheer on the hunger marchers. At lectures, she came across a well-built student – he was a champion hammer thrower – from Punjab, BPL (Baba) Bedi. He invited her to tea. Freda went along with a friend as a chaperone, as the rules required, and was charmed.”

The Revolutionary Life of Freda Bedi by Vicki Mackenzie is an account of an extraordinary Derby-born woman Freda Houlston. Born in 1911, educated at Oxford and married in 1933 to Baba Bedi bringing her to India at the height of the freedom struggle for Independence. She met her husband during the local meetings of the Majlis, the Indian students’ society, and listened to debates about Gandhi and India’s quest for freedom. According to Andrew Whitehead ( who too is working on a biography of Freda Bedi ; Derby Telegraph & The Wire ) “she went to the more tumultuous October Club, where left-wing students gathered to oppose fascism and cheer on the hunger marchers. At lectures, she came across a well-built student – he was a champion hammer thrower – from Punjab, BPL (Baba) Bedi. He invited her to tea. Freda went along with a friend as a chaperone, as the rules required, and was charmed.”

Along with her husband she became a left-wing activist — her socialist spirit was never to leave her even in later years upon conversion to Buddhism. Her marriage took her through Lahore ( in undivided India), Kashmir, Delhi, and Dalhousie. She witnessed Partition and though a firm follower of Gandhi and his non-violent means of struggle when in Kashmir she joined the women’s militia — the Women’s Self Defence Corps — started by some feisty members of the Communist Party affiliated with Sheikh Abdullah’s National Conference Party. Her husband was close to Sheikh Abdullah. Baba Bedi worked in the Kashmir administration “doing his part in promoting counterpropaganda” writing articles both in Kashmir and Delhi. The Bedi family spent five years in the state before the two men fell out in 1952 over their views on the Kashmir plebiscite, a political decision to let the people of Kashmir decide whether they wanted to join Pakistan or accede to India. She returned to Delhi to take on a government job as editor of Social Welfare, publication of the Central Social Welfare Board, part of the Ministry of Education. Social Welfare was written in English and translated into Hindi to reach as many people as possible. According to Vicki Mackenzie, Freda Bedi “chose with her heart — still wanting to help the poor and needy. The pay was low, but with her job came a government apartment”.

It was during a United Nations assignment to Burma that she had an epiphanic experience concerning Buddhism and decided to convert. She soon began to drift away from her material existence and in 1960s moved to Dalhousie where she established the Young Lamas Home School. She also gave shelter to the many Buddhist nuns who had fled Tibet after the Dalai Lama escaped. She created a system which went against the severely hierarchical and patriarchal structure of Buddhist monasteries but allowed the nuns to have a more democratic and responsible way of functioning.

Vicki Mackenzie documents this period of Freda Bedi’s life relying on extensive interviews with her three children — Ranga, the film actor Kabir Bedi and daughter, Guli — along with innumerable people who knew Freda. In fact she is unable to mask her surprise at how forthcoming everyone was with their recollections of Freda Bedi, sharing pictures and documents making Vicki remark that it was if this book was wanting to be written. Most importantly Vicki Mackenzie heard that the Dalai Lama himself would wonder why no book had ever been written as yet on Freda Bedi. Ever since going on a Buddhist retreat in 1976, Vicki Mackenzie’s writings have focused on Buddhism, reincarnation and role of women.

Even though Freda Bedi devoted the last twenty years of her life to Buddhism and left the family to work for its cause she remained extremely close to her children and husband. Her young daughter, Guli, who had been put into boarding school aged five recalls that every week punctually a letter would arrive from “mummy”. Even her sons knew that though they may have had an unorthodox upbringing, rich in experience but in financially straitened circumstances, they knew they could rely on their mother. For instance Kabir Bedi recounts he needed money to pay his fees at St. Stephen’s College and his mother advised him to ask a friend of theirs who readily gave the required amount. Her love for her family is also evident in a charming collection of poems she wrote for her eldest son, Ranga, called Rhymes for Ranga. It was published as a collection of rhymes in 2010.

Freda Bedi was the first European woman to convert to Buddhism. She was ordained in 1965. She is also credited with being the first nun to bring Tibetan Buddhism to the West. She was known as Sister Kechong Palmo although many Tibetans believed Freda to be an “emanation” of Tara, the female Buddha of Compassion in Action or the Divine Mother. Significantly whereever Freda went she was well-connected to the powers that be so was always able to get her way. In India, for instance, she knew politicians like the first prime minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru and his daughter Indira, diplomats and other prominent citizens. In England she counted among her friends Barbara Castle, a fiery left-wing cabinet minister in the 1960s and 70s. In fact when Freda returned to Delhi in 1979 to attend a world buddhist congress she stayed as a guest of the hoteliers Oberois at their five star luxury property. It was here that she passed away aged sixty-six years and was cremated on the Oberoi farm. It is believed that a couple of years later Freda Bedi was “reincarnated as a Tibetan girl, Jamyang Dolma Lama, the daughter of His Eminence Beru Khyentse Rinpoche, a respected lineage holder enthroned by the Sixteenth Karmapa. Born in Tibet, Beru Khyentse Rinpoche had known Freda Bedi well, and had set up his own center in Bodhgaya”.

Freda Bedi was the first European woman to convert to Buddhism. She was ordained in 1965. She is also credited with being the first nun to bring Tibetan Buddhism to the West. She was known as Sister Kechong Palmo although many Tibetans believed Freda to be an “emanation” of Tara, the female Buddha of Compassion in Action or the Divine Mother. Significantly whereever Freda went she was well-connected to the powers that be so was always able to get her way. In India, for instance, she knew politicians like the first prime minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru and his daughter Indira, diplomats and other prominent citizens. In England she counted among her friends Barbara Castle, a fiery left-wing cabinet minister in the 1960s and 70s. In fact when Freda returned to Delhi in 1979 to attend a world buddhist congress she stayed as a guest of the hoteliers Oberois at their five star luxury property. It was here that she passed away aged sixty-six years and was cremated on the Oberoi farm. It is believed that a couple of years later Freda Bedi was “reincarnated as a Tibetan girl, Jamyang Dolma Lama, the daughter of His Eminence Beru Khyentse Rinpoche, a respected lineage holder enthroned by the Sixteenth Karmapa. Born in Tibet, Beru Khyentse Rinpoche had known Freda Bedi well, and had set up his own center in Bodhgaya”.

Today it may seem commonplace to discuss Buddhism and encounter many celebrity converts such as Freda Bedi. But historically her contribution to Buddhism is extraordinarly. Her conversion and single-minded focus to do good constructively by the Tibetan Buddhists, soon after their spiritual leader — the Dalai Lama — fled Tibet for India was unusual for the day. As she was not only committed to the cause but would do anything in her power including calling upon her friends in senior positions to help her. Her persistence paid off and she was able to leave a well-defined legacy as is apparent in the Buddhist institutions she created at Dalhousie.

More than a century after she was born the important influence Freda Bedi had on Buddhists is slowly gaining traction. For instance Beyond Mud Walls a short documentary by a distant relative of hers, Nalini Paul, discusses the theatre performance she has conceptualised based Freda Bedi’s book.

Vicki Mackenzie’s biography of Freda Bedi is readable and well-researched. The effort to collect information to build a portrait of a formidable woman so many years after her death could not have been easy. Yet she did it. Despite Vicki Mackenzie’s fascinating account of an Englishwoman who made India her home during the Indian freedom struggle, it is quickly overshadowed by the stronger and better narrated time of Freda Bedi’s life as a Buddhist nun.

Vicki Mackenzie The Revolutionary Life of Freda Bedi: British Feminist, Indian Nationalist, Buddhist Nun Shambala Publications, Boulder, USA, 2017. Pb. pp.190 $16.95

13 May 2017