World Book Fair, Delhi, Jan 2017

( The world book fair was held in Delhi between 7-15 January 2017. It was another magnificent show put together by National Book Trust. I wrote about it for Scroll. The article was published on 29 Jan 2017. )

Three discoveries (and some footnotes) about readers and publishers from the World Book Fair

The death of reading has been greatly exaggerated. Yet again.

At first sight, the World Book Fair in Delhi looked like the scene of family holidays, with up to three generations milling around, some pulling suitcases on wheels filled with books. Actually, with the gradual disappearance of bookshops, the WBF has become an annual pilgrimage of sorts for book-buyers. Here are the three trends we discovered in the 2017 edition:

Children are reading, and reading, and reading…

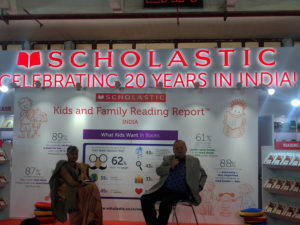

The findings of Scholastic India ‘s Kids & Family Reading Report (KFRR) confirm that parents most frequently turn to book fairs or book clubs to find books for their child, followed by bookshops and libraries. Eight out of ten children cite one of their parents as the person from whom they get ideas about which books to read for fun.

Curiously enough, what parents want in books for their children is often just what the children want too. Despite this being the digital age, six out of ten parents prefer that their children read printed books. This is particularly true for parents of children aged between six and eight. Perhaps surprisingly, a majority of children, 80%, agree: they will always want to read printed books despite the easy availability of ebooks.

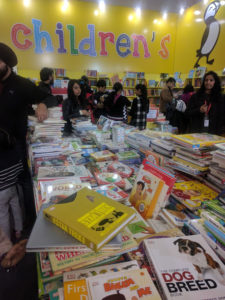

The findings of the report were confirmed independently by observing the phenomenal crowds in Hall 14 of the World Book Fair in Delhi in January, where the children’s literature publishers had been placed. These were astounding even on weekday mornings! Over the weekend queues to enter the hall snaked their way round Pragati Maidan to the food court and beyond. Remarkably, everyone was standing patiently.

The pavilions were overflowing with interested customers of all ages. Children scurried around like excited little pixies, flipping through books, making piles, some throwing tantrums with their parents demanding more than the budgets allowed, and many just plonking themselves on the carpets, absorbed in reading, oblivious to the crowds swirling around them.

The pavilions were overflowing with interested customers of all ages. Children scurried around like excited little pixies, flipping through books, making piles, some throwing tantrums with their parents demanding more than the budgets allowed, and many just plonking themselves on the carpets, absorbed in reading, oblivious to the crowds swirling around them.

Their interest was evident even during the packed storytelling sessions with writers like Ruskin Bond, Paro Anand and Prashant Pinge. This is corroborated by Neeraj Jain, Managing Director, Scholastic India, who said, “Using the findings of KFRR we created our stall as a reading zone.  The combination of books, events, interactions and dedicated reading zone made it a pleasurable experience.”

The combination of books, events, interactions and dedicated reading zone made it a pleasurable experience.”

Even adults were discovering new titles for their children. For instance, huddled around a shelf displaying Scholastic Teen Voice titles were a bunch of parents and teachers flipping through the books, exclaiming on their perceived difficulty of finding reading material for adolescents. The series in question contains page-turners built around crucial issues that matter to teens – bullying, drinking, technology, nutrition, fitness, goal-setting, depression, dealing with divorce, and responding to prejudice. Added Aparna Sharma, Managing Director, Dorling Kindersley Books: “We found that representatives from school libraries and other education institutions use this event to search out good books and order in bulk.”

And it wasn’t just the children’s publishers. Academic publishers like Oxford University Press had primary school children dragging their parents to browse through the titles, being familiar with the brand from their school textbooks. This held true even for DK books who, for the first time since they began participating in the fair, had a large table laden with books and generous shelf space in the Penguin Random House stall.

And it wasn’t just the children’s publishers. Academic publishers like Oxford University Press had primary school children dragging their parents to browse through the titles, being familiar with the brand from their school textbooks. This held true even for DK books who, for the first time since they began participating in the fair, had a large table laden with books and generous shelf space in the Penguin Random House stall.

Global publishers are more interested in publishing books from India than selling in India

The hall for international participants was thinly populated. Most of the participants seemed to have come for trade discussions. Many of these conversations were taking place on the sidelines or at other events outside the fair ground, since foreign participants, in particular, were daunted by the vast crowds. The launch of the Google Indic Languages cell at FICCI was announced at the CEOs’ breakfast meeting. Another significant announcement came from Jacks Thomas, Director, London Book Fair, where there will be a “Spotlight on India” at the Fair to mark the UK-India Year of Culture in March 2017.

Yet, as an overseas publisher said, “The World Book Fair is exclusively a business-to-consumer fair, quite unlike any they have in Europe”. This marked a significant shift of sorts. In the past the World Book Fair had been known for a range of international publishers, representing diverse cultures, languages and literature, selling their books directly to readers. Even India’s neighbouring countries used to participate in huge numbers, bringing across fine multiple literatures. This was not the case this time. As a result, long-time visitors to the fair were heard lamenting that its soul was missing – it felt as if an era had ended.

But people bought books, a lot of them

Despite the worry about demonetisation impacting sales, brisk business was done, with sales being 25% higher than in 2016, according to back-of-the-envelope estimates.

According to Kumar Samresh, Deputy Director, Publicity, National Book Trust, there were record footfalls at the 2017 edition of the fair, with 4 lakh complimentary multiple entry passes being supplemented 1.9 lakh individual entries based on ticket sales. There was also free entry schoolchildren, senior citizens, and, as usual, VIPs. Rajdeep Mukherjee, VP, Pan Macmillan India confirmed “a 30℅ rise in footfall, mainly led by young adult readers, but it was the Man Booker award winning title like The Sellout which has been a sellout literally!”

According to Kumar Samresh, Deputy Director, Publicity, National Book Trust, there were record footfalls at the 2017 edition of the fair, with 4 lakh complimentary multiple entry passes being supplemented 1.9 lakh individual entries based on ticket sales. There was also free entry schoolchildren, senior citizens, and, as usual, VIPs. Rajdeep Mukherjee, VP, Pan Macmillan India confirmed “a 30℅ rise in footfall, mainly led by young adult readers, but it was the Man Booker award winning title like The Sellout which has been a sellout literally!”

The other changes we observed

- The rising sale of textbooks and educational aids.

- The increasing popularity of books from franchises like Disney, Barbie, and Lego, or from brands like Marvel Comics and Geronimo Stilton.

- Older people cautioning youngsters to buy only “relevant” books.

- The overwhelming presence of religious publications.

- The preponderance of digital technology vendors, primarily in the area of educational publishing.

- Print-on-demand books (goodbye, inventories).

( All the images used in the article were taken by me during the fair.)

29 January 2017