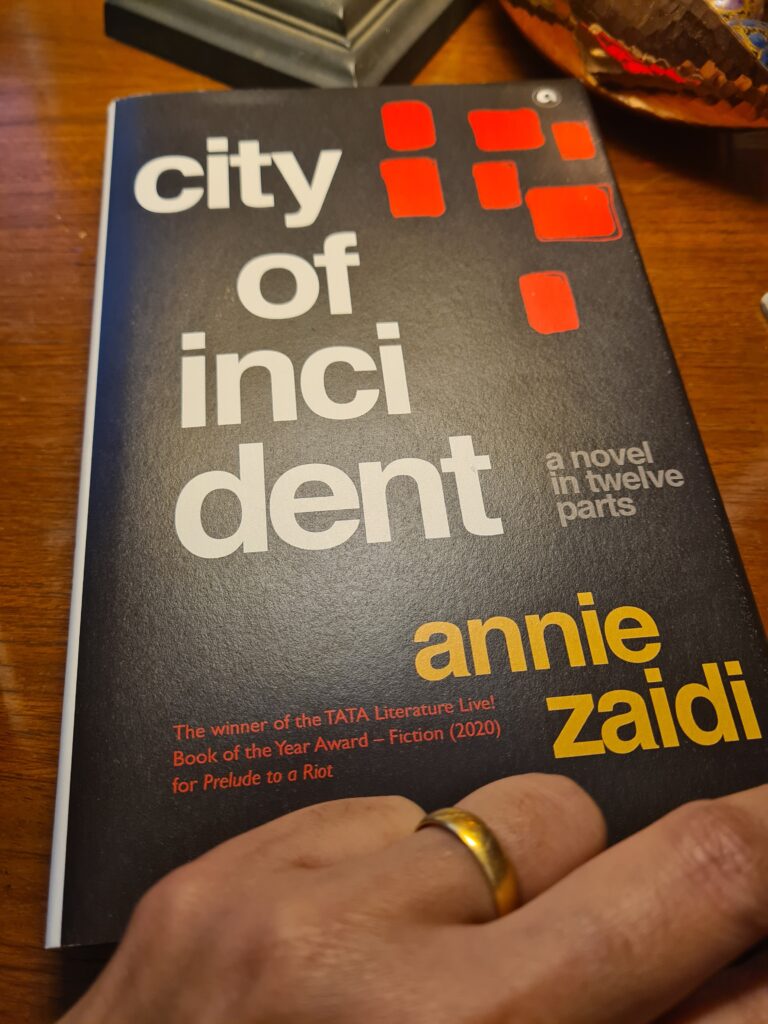

“City of Incident” by Annie Zaidi

Her mother likes telling stories about her. The time when she split open her knee and went all by herself to the dispensary. The time when she got her first pair of white ballerina shoes and was told to be careful not to dirty them, and how she became so cautious that she outgrew them before she had ever had a chance to wear them outside the house. The other thing her mother likes to say is, don’t get too caught up with thinking. She said it when her wedding was arranged with her cousin’s brother-in-law and she hadn’t quite finished college. Don’t think so much. The only choice one has is how to do the thing that’s got to be done. Do it easy and quick, it gets done easy and quick.

That’s how she does things, quick and quiet. They like her for it. They say how quiet and quick she is. When her first son arrived, they bought her a pair of gold jhumkas. Bracelets, the second time around. Glistening black eyes, fat with pride and relief, now watch her move around the house, on her feet all day, doing what’s got to be done: 6a.m., tea for the in-laws, 6.30, tea for the husband. Start chopping potatoes for the breakfast poha at 6.45. Bathe and dress the older one at 7.15, feed him at 7.30. Walk him tot he bus stop at 7.50. Call the others to breakfast at 8.30. Feed the younger one before aeting herself. Take stock of the kitchen at 10. Start cooking lunch at 10.30.

Unknown to them, after the school bus has taken away her first child, she stops for a secret glug of time. … She doesn’t dare stay longer than ten minutes. The other mothers would have returned to the building and her family will start to wonder. Still, she stretches out the minute as far as it will go.

( p.46-7) “A Housewife Walks out with her Children but Fails to Board the Train”

Award-winning writer, Anni Zaidi’s new short story collection, City of Incident: A Novel in Twelve Parts, is of nameless characters who live in the city. It is published by Aleph Book Company. The short story titles are the only indication of the character’s identity — policeman, salesgirl, bank teller, wood worker, housewife, beggar, security guard, adulterous man, trinket seller, and manager. These descriptions are very similar to how stories are shared by Indians in languages apart from English. Stories begin from the middle, consist of nameless characters and move ahead and equally abruptly end.

annie Zaidi’s keen eye is extraordinary. She observes with a minuteness that is breathtaking. Her stories are reminiscent of J. Alfred Prufrock:

Shall I say, I have gone at dusk through narrow streets

And watched the smoke that rises from the pipes

Of lonely men in shirt-sleeves, leaning out of windows? …

Annie Zaidi, probably like many of her readers, has imagined stories about the many nameless people in a crowd. Zaidi has taken it a step further — she has written down the stories. Short sketches are meant to be packed with detail, not a word out of place, and this is exactly the vividness that characterises this collection. And yet there is a sense of universality about the sketches as the reader will instantly recognise such characters in their lives too. The empathy with which she writes is at the heart and soul of every story. The stories linger with the reader after the book is closed.

The universality of her characters is also played out by the ordinariness of their roles. Community, caste, and religion are not the identifying features of these stories. These scenarios can belong to anyone. It comes as a shock to the reader to realise this. Everyone has a story to tell. This collection proves it as long as one is prepared to look beyond the nameless faces and make the effort to understand. City of Incident: A Novel in Twelve Parts puts the spotlight on the ordinary challenges, ordinary dreams, ordinary ambitions, of the ordinary folk. The significance of this is accentuated given that Annie Zaidi is known for her sharp commentaries through the arts on sectarian violence. The grief and distress of the ongoing pandemic, coupled with the normalisation of communal hatred in society, has been horrific. Yet, Annie Zaidi has chosen to bring the conversation back to where it is essential — the common man and his/her daily struggles. Annie Zaidi epitomises the role of a writer/artist in society; and as always, she does it with calm fortitude and grace.

Read it.

23 Jan 2022