Interview with Susan Van Metre, Executive Editorial Director, Walker Books US

Susan Van Metre is the Executive Editorial Director of Walker Books US, a new division of Candlewick Press and the Walker Group. Previously she was at Abrams, where she founded the Amulet imprint and edited El Deafo by Cece Bell, the Origami Yoda series by Tom Angleberger, the Internet Girls series by Lauren Myracle, They Say Blue by Jillian Tamaki, and the Questioneers series by Andrea Beaty and David Roberts. She lives in Brooklyn with her husband, Pete Fornatale, and their daughter and Lab mix.

Susan and I met when we were a part of the Visiting International Publishers delegation organised by the Australia Council and Sydney Writers Festival. It was an incredibly enriching time we spent with other publishing professionals from around the world. Meeting Susan was fabulous as Walker Books is synonymous with very high standards of production in children’s literature. Over the decades the firm has established a formidable reputation. Susan very kindly agreed to do an interview via email. Here are lightly edited excerpts.

1. How did you get into

publishing children’s literature? Why join children’s publishing at a time when

it was not very much in the public eye?

I never stopped reading children’s books, even as a teen and young adult. I have always been in love with story. I was a quiet, lonely young person and storytelling pulled me out of my small world and set me down in wonderful places in the company of people I admired. I couldn’t easily find the same richness of plot and character in the adult books of the era so stuck with Joan Aiken and CS Lewis and E Nesbit and Ellen Raskin. And I loved the books themselves, as objects, and, in college, had the idea of helping to make them. I applied to the Radcliffe Publishing Course, now at Columbia, met some editors from Dutton Children’s Books/Penguin there, and was invited to interview. Though I couldn’t type at all (a requirement at the time), I think I won the job with my passionate conviction that the best children’s books are great literature, and arguably more crucial to our culture in that they create readers.

2. How do you commission books? Is it always through literary agents?

Most of the books I publish come from agents but occasionally I’ll reach out to a writer who has written an article that impressed me and ask if they have thought of writing a book. Recently, I bought a book based on hearing the makings of the plot in a podcast episode.

3. How have the books you read as a child formed you as an editor/publisher? If you worry about the world being shaped by men, does this imply you have a soft corner for fiction by women? ( Your essay, “Rewriting the Stories that Shape Us”)

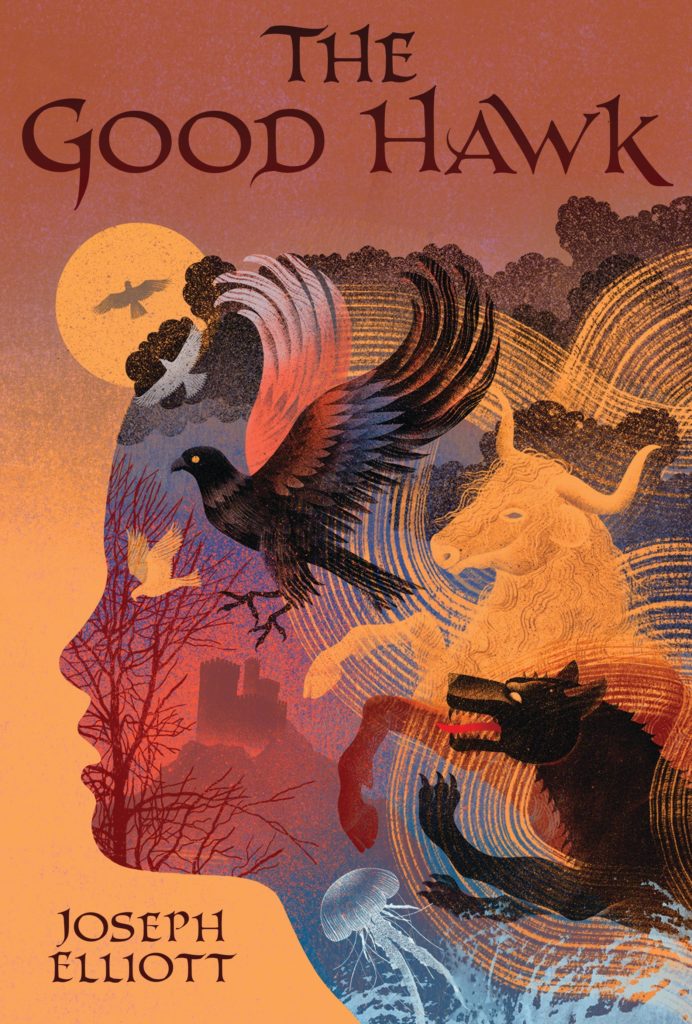

What a good question. I definitely look for books with protagonists that don’t typically take centre stage, whether it’s a girl or a character of colour or a character with a disability. I have always been attracted to heroes who are underdogs or outsiders, ones that prevail not because they have special powers or abilities but because they have determination and heart. I am in love with a book on our Fall ’19 list, a fantasy whose hero is a teen girl with Down syndrome. It’s The Good Hawk by Joseph Elliott. I have never met a character like Agatha before—she’s all momentum and loyalty. Readers will love her.

4. Who are the writers/artists that have influenced your publishing career/choices?

I am very influenced by brainy, hardworking creators like Ellen Raskin and Cece Bell and Mac Barnett and Sophie Blackall and Jillian Tamaki. I admire a great work ethic, outside-the-box thinking, an instinct for how words and images can work together to create a richly-realized story, and respect for kids as fully intelligent and emotional beings with more at stake than many adults.

5. As an employee- and author-owned company, Candlewick is used to working collaboratively in-house and with the other firms in the Walker groups. How does this inform your publishing programme? Does it nudge the boundaries of creativity?

There is so much pride at Walker and Candlewick. Owning the company makes us feel that much more invested in what we are making because it is truly a reflection of us and our values and tastes. Plus, we only make children’s books and thus put our complete resources behind them. There are no pesky, costly adult books and authors to distract us. And I think the strong lines of communication amongst the offices in Boston, New York, London, and Sydney mean that we have a good global perspective on children’s literature and endeavour to make books with universal appeal. I think all these factors contribute to innovation and quality.

6. You have spent many years in publishing, garnering experience in three prominent firms —Penguin USA, Abrams and Candlewick Press. In your opinion have the rules of the game for children’s publishing changed from when you joined to present day?

Oh, definitely. When I started, children’s publishing was a quiet corner of the business, mostly dependent on library sales. There was no Harry Potter or Hunger Games or Wimpy Kid; no great juggernauts driving millions of copies and dollars. And not really much YA. YA might be one spinner rack at the library, not the vast sections you see now, full of adult readers. Now children’s and YA is big business and mostly bright spots in the market. The deals are bigger and the risk is bigger and the speed of business is so much faster!

7. Do you discern a change in reading patterns? Do these vary across formats like picture books, novels, graphic novels? Are there noticeable differences in the consumption patterns between fiction and nonfiction? Do gender preferences play a significant role in deciding the market?

I think we are in a great time for illustrated books, whether they are picture books, nonfiction, chapter books, or graphic novels. And now children can move from reading picture books to chapter books to graphic novels without giving up full colour illustrations as they age. And why should they? Visual literacy is so important to our internet age—an important way to communicate online.

8. One of the iconic books of modern times that you have worked upon are the Diary of a Wimpy Kid series. Tell me more about the back story, how it came to be etc. Also what is your opinion on the increasing popularity of graphic novels and how has it impacted children’s publishing?

I am not the editor of the Wimpy Kid books—that’s Charles Kochman—but I was lucky enough to help sign them up and bring them to publication as the then head of the imprint they are published under, Amulet Books. Charlie comes out of comics so when he saw the proposal for Wimpy Kid, which had been turned down elsewhere, he understood the skill and appeal of it. I have NEVER published anything that took off so immediately. I think we printed 25,000 copies, initially, and we sold out of them in two weeks. It showed how hungry readers were for that strong play of words and images, and how they longed for a protagonist who was flawed but who didn’t have to learn a lesson. Adult readers have many such protagonists to enjoy but they are rarer in kids’ books.

9. Walker Books are inevitably heavily illustrated, where each page has had to be carefully designed. Have any of your books been translated? If so what are the pros and cons of such an exercise?

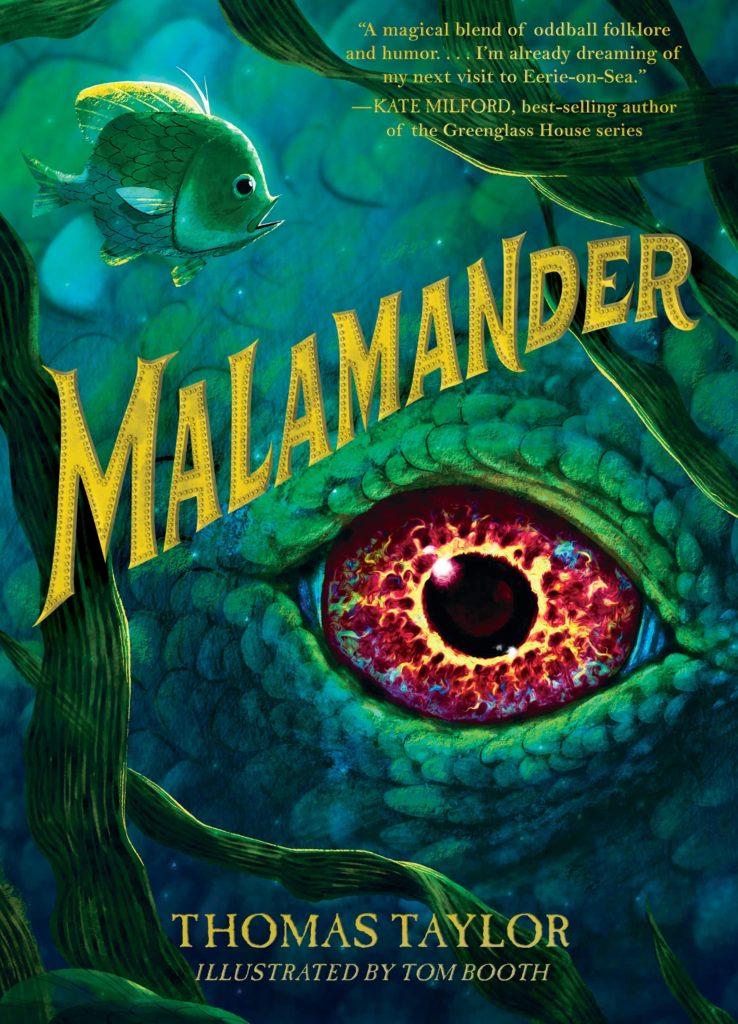

Our lead Fall title, Malamander, is illustrated and has been sold in a dozen languages. I think illustration can be a big plus in conveying story in a universally accessible way.

10. The Walker Group is known for its outstanding production quality of printed books. Has the advancement of digital technology affected the world of children’s publishing? If so, how?

I think they incredible efficiency of modern four-colour printing has allowed us to spend money on other aspects of the book, like cloth covers or deckled edges. That sort of thing. Children’s books are incredible physical objects these days.

11. Walker Books’ reputation is built on its ability to be creatively innovative and constantly adapt to a changing environment. How has the group managed to retain its influence in this multimedia culture?

First, thank you for saying so! I think the rest of media still looks to book publishing for great stories and as a house that has always invested in talent, we are lucky enough to have stories that work across many forms of media.

12. Have any of books you have worked upon in your career been banned? If so, why? What has been the reaction?

Yes. In fact, I am working with Lauren Myracle on a young adult novel, publishing in Spring ’21, called This Boy. Lauren is the author of the ttyl series, which was on the ALA’s Banned Book list for many years. It was challenged for its depictions of teenage sexuality. I was raised to be modest and rule following so my personal reaction was horror—especially when parents started phoning me directly to complain—but I feel so strongly that kids and teens deserve to read about life as it really is—not just as we wish it would be. So I came to be proud of the designation. Nothing is scarier than the truth.

Bibliography:

Hannah Lambert (2010) Sebastian Walker and Walker Books: A Commercial Case Study, New Review of Children’s Literature and Librarianship, 15:2, 114-127, DOI: 10.1080/13614540903498885. Published online: 03 Feb 2010.

25 Sept 2019