Tuesday Reads ( Vol 8), 13 August 2019

Dear Reader,

It has to be the oddest concatenation of events that when the abrogation of Article 370 was announced by the Indian Government on 5 August, I was immersed in reading Colson Whitehead’s The Nickel Boys and Mirza Waheed’s Tell Her Everything. Two mind-blowing powerful novels that are only possible to read when the mental bandwith permits it. Colson Whitehead’s novel is as darkly horrific as it imagines the time in a reform school when racial segregation was openly practised. It is extremely disturbing to read it Mirza Waheed’s novel is an attempt by the narrator to communicate to his daughter about his past as a doctor and why he chose to look the other way while executing orders of the powers that be. Orders that were horrific for it required the narrator surgical expertise to amputate the limbs of people who had been deemed criminals by the state. Tell Her Everything is a seemingly earnest attempt by the narrator to convince his estranged daughter that what he did was in their best interests, for a better life, a better pay, anything as long as his beloved daughter did not have to face the same straitened circumstances that he was all too familiar with while growing up. It is the horror of the justification of an inhuman and cruel act by the surgeon that lingers well after the book is closed. Such savage atrocities are not unheard of and sadly continue to be in vogue. And then I picked up Serena Katt’s debut graphic novel Sunday’s Child which tries to imagines her grandfather’s life as a part of Hitler’s Youth. She also questions his perspective and the narrative is offered in the form of a dialogue. She refers to the “chain hounds” who hunted, and executed, deserters. Something not dissimilar to the incidents documented in The Nickel Boys too.

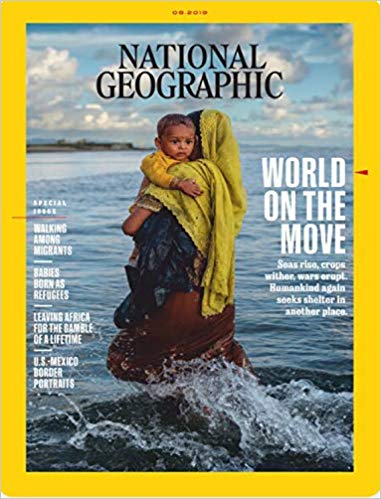

Then this month’s issue of National Geographic magazine arrived. It’s cover story is on migration and migration called “World on the Move”. In it the writer Mohsin Hamid has an essay, “In the 21st century, we are all migrants“. We are told not only that movement through geographies can be stopped but that movement through time can be too, that we can return to the past, to a better past, when our country, our race, our religion was truly great. All we must accept is division. The division of humanity into natives and migrants. … It is the central challenge and opportunity every migrant offers us: to see in him, in her, the reality of ourselves.”

To top it I read Michael Morpurgo’s Shadow. It is about the friendship of two fourteen-year-olds, Matt and an Afghan refugee, Aman. Shadow is the bomb sniffer dog who adopted Aman as he and his mum fled Bamiyan in Afghanistan from the clutches of the Taliban. The mother-son pair moved to UK but six years after being based there were being forcibly deported back to Afghanistan despite saying how dangerous their homeland continued to be. Shadow, a young adult novel, is set in a detention camp called Yarl’s Wood, Bedfordshire, UK. While terrifying to read, Morpurgo does end as happens with his novels, with a ray of hope for the young reader. Unfortunately reality is very different. So while helping tiddlers connecting the dots with reality is a sobering exercise for them, it can be quite an emotional roller coaster for the adults.

In an attempt to look the other way, I read a delightful chapter book called Tiny Geniuses : Set the Stage! by Megan E. Bryant. It is about these historical figures who are resurrected into present day as mini figures by a couple of school boys. In this particular book, the two figures wished for are Benjamin Franklin and Ella Fitzgerald. It can make for some amusing moments as the school boys try and complete their school projects. A delightful concept that is being created as an open-ended series arc. It did help alleviate one’s gloomy mood a trifle but only just.

Read this literature with a strong will, patient determination and a strong stomach. Otherwise read the daily papers. For once you will find that the worlds of reality and fiction collide.

15 August 2019