An article published in Asian Age , 9 Sept 2012

Bookmark Bollywood

September 9, 2012 By Jaya Bhattacharji Rose

Tags: Bollywood publications

Over the years fascinating behind-the-scenes documentaries about cinema have been made yet little literature has been published. Even veterans like Oscar-winner costume designer Bhanu Athaiya and choreographer Shiamak Davar have focused on their professions; only recently have they opted to write biographies. Or Kareena Kapoor’s forthcoming style diary of a “Bollywood diva” where she will give a peek into her life and reveal her beauty secrets. By comparison a relatively new entrant to films award-winning actress Tisca Chopra has taken the plunge to write a book that aims to demystify Bollywood from the perspective of an actor/model — with its many stories, anecdotes and first-hand experiences. All of which begs to ask the question — why are so many books being published on Indian cinema now?

Dadasaheb Phalke’s Raja Harishchandra, India’s first full-length film, was released in May 1913, so 2012 is being celebrated as Indian cinema’s centenary. In fact the theme for the World Book Fair, Feb 2012 organised by National Book Trust was Indian Cinema.

Udayan Mitra, Publisher, Allen Lane, Penguin Books India says, “There is more interest now than ever before in reading about the world of cinema — the making of films, celebrity lives, the reception of movies. This indicates a readership that is more clued in than ever, and curious about cultural productions.”

This statement is corroborated by Jerry Pinto, author of Helen, the life and times of an H-Bomb, “There is a new interest in Bollywood because we are now a nation that can be confident of our own cultural products. It takes self-confidence to be able to declare oneself for kitsch. To say that one appreciates kitsch, one must believe that others see us as having good taste and so we are capable of appreciating that which lacks good taste but with such bravura that it attains to the status of kitsch. This is what is happening to Bollywood right now; you can see it in films like Om Shanti Om, Action Replayy, Luck by Chance. And this has translated into an awareness of the possibilities of publishing.”

Some of the forthcoming books focused upon the industry are HarperCollins’ list of film monologues. It consists of commentaries, analysis, reading of the film subtext and the making of the film. Forthcoming are Amar Akbar Anthony by Sidharth Bhatia, Pakeezah by Meghnad Desai, Mughal-e-Azam by Anil Zankar, and Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak by Gautam Chintamani. Other titles are a biography of S.D. Burman by Sathya Saran and of Sahir Ludhianvi by Akshay Manwani, plus A Southern View: Cinema of the South edited by M.K. Raghavendra.

According to Pradipta Sarkar, Commissioning Editor, Rupa, “Cashing in upon the success of superstar Rajinikanth’s 2010 film Enthiran/Robot that broke box-office records of all kinds and all notions of regional/ linguistic barriers led us to publish this year Rajini’s Punchtantra: Business and Life Management the Rajinikanth Way by P.C. Balasubramanian and Raja Krishnamoorthy — a unique self-help book and management guide that uses the superstar’s legendary punchlines as mantras for work as well as life.”

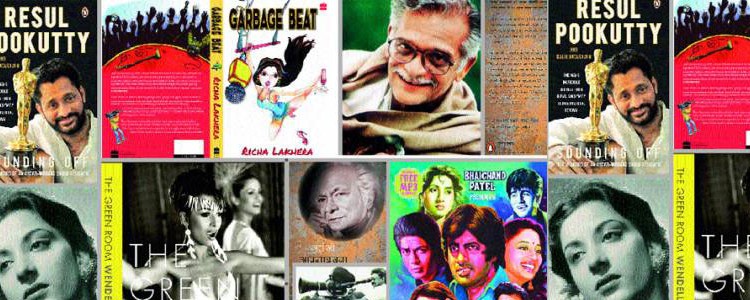

Penguin Books India is slated to publish the definitive biography of Rajinikanth by Naman Ramachandran; Conversations with Mani Ratnam by Baradwaj Rangan; Oscar-winning sound designer Resul Puokootty’s autobiography Sounding Off and a cinema diary for the year 2013 called A Sideways Glance at Hindi Cinema by Nasreen Munni Kabir.

Neeta Gupta, Publisher, Yatra Books, who recently announced a co-publishing agreement with Westland Books says, “I think Bollywood has been ignored for the longest time — and we as publishers are now in the process of addressing this lacuna. I found that there is a huge demand for books on musicians, lyricists and singers. We are now working on a biography of Mohammad Rafi (My Abba — A Memoir by Yasmin Khalid Rafi).”

Om Books has published film journalist Anna M.M. Vetticad’s Adventures of an Intrepid Film Critic, a humorous look at the dynamics that drives the essential and fringe Bollywood; to be followed by Housefull: The Golden Age of Hindi Cinema edited by Ziya Us Salam on cinema of the Fifties and the Sixties; Shammi Kapoor: The Untold Tale by Rauf Ahmed; and Anupama Chopra and Tula Goenka’s books on interactions with Indian directors, actors, with analytical pieces as well.

It is probably a coincidence that in 2012 publishing houses are suddenly producing several fascinating books on the industry. In fact R.D. Burman: The Man, The Music by Anirudha Bhattacharjee and Balaji Vittal won the National Award for Best Book on Cinema, 2011.

For a while now there have been books on Indian cinema across genres — biographies, memoirs, screenplays and academic commentaries. For instance, Om Puri: Unlikely Hero (which caused a few ripples with its scandalous revelations); Shaukat Kaifi’s memoir Kaifi and I; Dadasaheb Phalke: The Father of Indian Cinema by Bapu Vatave; Guru Dutt, A Life in Cinema by Nasreen Munni Kabir. Publishers, authors and film journalists are of the opinion that the centenary celebrations gave a boost to the number of books being produced on Indian cinema. But the readership for this niche market has been growing steadily. A strong indicator of this has been the establishment by Om Book Shop of India’s first exclusive cinema book store at PVR Director’s Cut, Delhi. According to Dipa Chaudhuri, Managing Editor, Om Books, “The constituency of readers interested in cinema titles is definitely on the rise, a sign that cinema is here to stay on a publisher’s list.”

Rachel Dwyer, Professor of Indian Cultures and Cinema at SOAS, University of London feels that the centenary may be the immediate reason for a number of books appearing on Indian cinema but this has been increasing over the last decade. “I think publishing houses are looking for them because they sell well — or at least the biographies do — and also because I think they’re looking for a big book on Indian cinema — although no one seems to know what that would be.”

London-based documentary filmmaker and author of 12 books on Indian cinema, Nasreen Munni Kabir sums it up well when she tracks the recent history of publications on Indian cinema. She recounts, “When I first wrote a book on Guru Dutt in 1996, there were very few books in English on popular cinema, and this situation was largely unchanged till the early 2000s. I think the middle classes’ revived interest in Hindi cinema really took off by the mid-90s, perhaps with the popularity of the Khans, the middle-class youth found Hindi film ‘cool’. And it is most likely that this section of the audience would be the ones buying and reading English language books, so it was natural that a spate of publications on the subject would follow. Universities all around the world, including in India, also started courses on Indian film, so the demand for publications of film books grew. Today film celebrities wield a tremendous power, so learning more about stars and films has intensified.”

The writer is an international publishing consultant and columnist