Book Post 52: 25 Nov – 17 Dec 2019

Book Post 52 includes some of the titles received in the past few weeks.

17 Dec 2019

Teamwork, the producers of Jaipur Literature Festival, create JLF in Belfast or thereabouts from 21-23 June 2019. Jaipur Belfast has announced an exciting programme. These are being organised at two venues: The Lyric Theatre (22 June) and Seamus Heaney Homeplace (23 June). Tickets may be booked at the official website for JLF Belfast.

The curtain raiser for the event was organised on 4 June at the British Council, New Delhi. Speaking at the event Sanjoy Roy, Managing Director, Teamwork Arts said, “This is a living bridge — it’s about people, ideas, sport, books and above all, about literature. Today, dialogue is becoming more and more important. We have to continue what we do best that without political affiliation people come together to discuss and disagree peacefully. In Belfast people wear their wounds on their sleeves much as we Indians wear it.” He expanded on this sentiment in an article for the Irish Times, “Jaipur Literature Festival comes to Belfast: celebrating each other’s stories” ( 7 June 2019)

Namita Gokhale, co-director, JLF, said “JLF Belfast looks at shared histories through themes of identity and selfhood. Tara Gandhi Bhattacharjee, Mahatma Gandhi’s granddaughter, discusses the nature of non-violence. We ponder the puzzles of identity, the power of poetry, the mysteries of word, the flavours of Asian cuisine, the future of AI by Marcus du Sautoy. We revisit the poetry of Yeats and Tagore and explore the echoes of each in the other.”

William Dalrymple, co-director, JLF, added that JLF Belfast attempts to look at the scars of these different partitions.

At the curtain raiser a wonderful discussion was organised on Kalidas and Shakespeare. It was moderated by translator Gillian Wright. The panelists included academics Dr R. W. Desai and Prof. Harish Trivedi. Here is the recording I made with Facebook Live.

Meanwhile as the weekend draws near Irish writer Paul McVeigh has been posting fabulous tweets on the prepatory work. Here is a glimpse:

Go for it, people! This sounds like a promising event.

20 June 2019

The Begum: A Portrait of Ra’ana Liaquat Ali Khan, Pakistan’s Pioneering First Lady by Deepa Agarwal and Tehmina Aziz Ayub is a good account of a fascinating woman. Begum Ra’ana Liaquat Ali Khan’s life mirrors the history of the subcontinent. Namita Gokhale, writer and co-director, Jaipur Literature Festival, wrote a wonderful introduction to the book. The following extracts from the introduction have been published with permission of the publisher, Penguin Random House India.

****

Reflecting on how and what to write while introducing this important biography, I wonder once again if it is one or two books I have before me. This collaborative account, co-authored by Deepa Agarwal and Tahmina Ayub, mirrors the fissures and fault lines that divided Begum Ra’ana Liaquat Ali Khan’s life into two astonishingly symmetrical halves. A well-researched portrayal of an intrepid and passionate woman, it presents her personal narrative and political convictions, and mirrors the history of the subcontinent, in a timeline truncated by the uncompromising contours of the Radcliffe Line.

Sir Cyril Radcliffe arrived in India on 8 July 1947. The eminent barrister was given all of five weeks to divide up a nation, a culture, a people. His brief was to ‘demarcate the boundaries of the two parts of the Punjab on the basis of ascertaining the contiguous majority areas of Muslims and non-Muslims’. A handful of men—five persons in each ‘boundary commission’ for Bengal in the east and Punjab in the west—worked day and night on a hurried and ignominious exit from an increasingly precarious and unstable empire. Equal representation given to politicians from the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League, each hostile and intractable in their positions, only added to the tensions.

In New Delhi, at 8 Hardinge Road, a sprightly forty-three year-old woman, all of five feet tall, was hastily putting together some personal belongings. Begum Ra’ana Liaquat Ali Khan was preparing to depart in a government aeroplane for Karachi airport, where her husband Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan was soon to be sworn in as the first prime minister of Pakistan.

The future first lady was leaving her magnificent double storeyed home, set in three acres of garden, for an unknown and uncertain life in a newly formed nation. This elegant colonial bungalow (now 8 Tilak Marg) had been her home since her marriage. Both her sons, Ashraf and Akber, had been born here. 8 Hardinge Road had become the focal hub for the activities of the Muslim League. Her husband had been appointed finance minister of the interim government, and indeed the papers for the interim budget presented on 2 February 1946 had been taken directly from his home to Parliament House.

Not so far away, at 10 Aurangzeb Road, Muhammad Ali Jinnah had also made preparations to depart Delhi, and India. However, he had been more pragmatic than the idealistic and high-minded Liaquat Ali and had sold his house to the industrialist Ramkrishna Dalmia for Rs 3 lakh. Liaquat and his wife Ra’ana, on other hand, had decided to gift their home to Pakistan—it was to become the residence of the new nation’s future high commissioner. ‘Gul-i-Ra’ana’, the bungalow that her adoring husband had named after her, would henceforth be known as ‘Pakistan House’. Their vast and eclectic library was also gifted to the new nation in which they had invested their hopes and lives.

What were the thoughts and emotions that jostled in her mind and heart as she observed all that she had struggled for come to fruition, even as the looming shadow of Partition prepared to bathe the two nations in a fierce spasm of blood and sacrifice?

Begum Ra’ana Liaquat Ali Khan, born Irene Ruth Margaret Pant on 13 February 1905, to an apostate Brahmin lineage, was a practising Christian until 1933. After her marriage, she converted to Islam and was renamed Gul-i-Ra’ana. This fiercely independent lady, who carried her myriad identities within a core self of unchanging conviction, departed this world on 13 June 1990, by which time she was known, recognized and honoured as ‘Madar-e-Pakistan’ or ‘Mother of Pakistan’.

The first half of her life was spent in undivided India, where she transited two religious identities, and repudiated a third, albeit through her grandfather. With almost mathematical precision, her eighty-six years were divided into forty-three years plus some months in each of her two lives. She was an intimate witness to history—the two nations, the bifurcation of East and West Pakistan, the creation of Bangladesh, the course of the Cold War, the rise of Gorbachev, and the increasingly unequivocal hold of the army in Pakistan. From Jinnah, through Zulfikar Bhutto and to General Zia-ul-Haq, she spoke her mind and held her own.

Before her marriage, she was a professor of economics in Delhi’s prestigious Indraprastha College. Her doctoral thesis had been on women in agriculture in rural Uttar Pradesh. Begum Ra’ana was an important, even crucial, catalyst to Jinnah’s return to politics and the unfolding of the ‘two-nation theory’. In the summer of 1933, she and her husband met Jinnah in his home in Hampstead and appealed to him to return to India. Unafraid to champion difficult causes, she was radical in her attempts to bring about gender equity within the Islamic State of Pakistan and unflinching in her defence of her friend Zulfikar Ali Bhutto when he was facing the gallows. And at all times, she was charming and gracious as an accomplished diplomat and stateswoman.

Where then did she get her steely resolve and infinite reserve of strength? How did she negotiate the transitions and transformations of history with such seeming ease? I have always been fascinated by this formidable woman, and her ability to stand tall in an overwhelmingly patriarchal society even after losing her husband, with no grown male—or indeed female—relatives to support her in the newly birthed nation of Pakistan.

…

Begum Ra’ana was born Irene Pant. We share maiden surnames, and a common ancestry. I was born Namita Pant, and a faded family tree documents these connections, with a branch of it cryptically cut off. With his conversion to Christianity, her grandfather Taradutt Pant had placed himself outside the pale of caste and kinship. Yet whenever I encountered the half-told stories of Begum Ra’ana, I could sense the mountain grit in her, the legendary strength that comes so naturally to Kumaoni women. There was also a strong family resemblance—to my sister, to several of my aunts. I wanted to know more about her, to understand her as a determined woman, a thinking, feeling human, a creature of her times and circumstances.

….

29 May 2019

I recently contributed to How to Get Published in India edited by Meghna Pant. The first half is a detailed handbook by Meghna Pant on how to get published but the second half includes essays by Jeffrey Archer, Twinkle Khanna, Ashwin Sanghi, Namita Gokhale, Arunava Sinha, Ravi Subramanian et al.

Here is the essay I wrote:

****

AS LONG as I can recall I have wanted to be a publisher. My first ‘publication’ was a short story in a newspaper when I was a child. Over the years I published book reviews and articles on the publishing industry, such as on the Nai Sarak book market in the heart of old Delhi. These articles were print editions. Back then, owning a computer at home was still a rarity.

In the 1990s, I guest-edited special issues of The Book Review on children’s and young adult literature at a time when this genre was not even considered a category worth taking note of. Putting together an issue meant using the landline phone preferably during office hours to call publishers/reviewers, or posting letters by snail mail to publishers within India and abroad, hoping some books would arrive in due course. For instance, the first Harry Potter novel came to me via a friend in Chicago who wrote, “Read this. It’s a book about a wizard that is selling very well.” The next couple of volumes were impossible to get, for at least a few months in India. By the fifth volume, Bloomsbury UK sent me a review copy before the release date, for it was not yet available in India. For the seventh volume a simultaneous release had been organised worldwide. I got my copy the same day from Penguin India, as it was released by Bloomsbury in London (at the time Bloomsbury was still being represented by Penguin India). Publication of this series transformed how the children’s literature market was viewed worldwide.

To add variety to these special issues of The Book Review I commissioned stories, translations from Indian regional languages (mostly short stories for children), solicited poems, and received lovely ones such as an original poem by Ruskin Bond. All contributions were written in longhand and sent by snail mail, which I would then transfer on to my mother’s 486 computer using Word Perfect software. These articles were printed on a dot matrix printer, backups were made on floppies, and then sent for production. Soon rumours began of a bunch of bright Stanford students who were launching Google. No one was clear what it meant. Meanwhile, the Indian government launched dial-up Internet (mostly unreliable connectivity); nevertheless, we subscribed, although there were few people to send emails to!

The Daryaganj Sunday Bazaar where second-hand books were sold was the place to get treasures and international editions. This was unlike today, where there’s instant gratification via online retail platforms, such as Amazon and Flipkart, fulfilled usually by local offices of multi-national publishing firms. Before 2000, and the digital boom, most of these did not exist as independent firms in India. Apart from Oxford University Press, some publishers had a presence in India via partnerships: TATA McGraw Hill, HarperCollins with Rupa, and Penguin India with Anand Bazaar Patrika.

From the 1980s, independent presses began to be established like Kali for Women, Tulika and KATHA. 1990s onwards, especially in the noughts, many more appeared— Leftword Books, Three Essays, TARA Books, A&A Trust, Karadi Tales, Navayana, Duckbill Books, Yoda Press, Women Unlimited, Zubaan etc. All this while, publishing houses established by families at the time of Independence or a little before, like Rajpal & Sons, Rajkamal Prakashan, Vani Prakashan etc continued to do their good work in Hindi publishing. Government organisations like the National Book Trust (NBT) and the Sahitya Akademi were doing sterling work in making literature available from other regional languages, while encouraging children’s literature. The NBT organised the bi-annual world book fair (WBF) in Delhi every January. The prominent visibility in the international English language markets of regional language writers, such as Tamil writers Perumal Murugan and Salma (published by Kalachuvadu), so evident today, was a rare phenomenon back then.

In 2000, I wrote the first book market report of India for Publisher’s Association UK. Since little data existed then, estimating values and size was challenging. So, I created the report based on innumerable conversations with industry veterans and some confidential documents. For years thereafter data from the report was being quoted, as little information on this growing market existed. (Now, of course, with Nielsen Book Scan mapping Indian publishing regularly, we know exact figures, such as: the industry is worth approximately $6 billion.) I was also relatively ‘new’ to publishing having recently joined feminist publisher Urvashi Butalia’s Zubaan. It was an exciting time to be in publishing. Email had arrived. Internet connectivity had sped up processes of communication and production. It was possible to reach out to readers and new markets with regular e-newsletters. Yet, print formats still ruled.

By now multinational publishing houses such as Penguin Random House India, Scholastic India, Pan Macmillan, HarperCollins India, Hachette India, Simon & Schuster India had opened offices in India. These included academic firms like Wiley, Taylor & Francis, Springer, and Pearson too. E-books took a little longer to arrive but they did. Increasingly digital bundles of journal subscriptions began to be sold to institutions by academic publishers, with digital formats favoured over print editions.

Today, easy access to the Internet has exploded the ways of publishing. The Indian publishing industry is thriving with self-publishing estimated to be approximately 35% of all business. Genres such as translations, women’s writing and children’s literature, that were barely considered earlier, are now strong focus areas for publishers. Regional languages are vibrant markets and cross-pollination of translations is actively encouraged. Literary festivals and book launches are thriving. Literary agents have become staple features of the landscape. Book fairs in schools are regular features of school calendars. Titles released worldwide are simultaneously available in India. Online opportunities have made books available in 2 and 3-tier towns of India, which lack physical bookstores. These conveniences are helping bolster readership and fostering a core book market. Now the World Book Fair is held annually and has morphed into a trade fair, frequented by international delegations, with many constructive business transactions happening on the sidelines. In February 2018 the International Publishers Association Congress was held in India after a gap of 25 years! No wonder India is considered the third largest English language book market of the world! With many regional language markets, India consists of diverse markets within a market. It is set to grow. This hasn’t gone unnoticed. In 2017, Livres Canada Books commissioned me to write a report on the Indian book market and the opportunities available for Canadian publishers. This is despite the fact that countries like Canada, whose literature consists mostly of books from France and New York, are typically least interested in other markets.

As an independent publishing consultant I often write on literature and the business of publishing on my blog … an opportunity that was unthinkable before the Internet boom. At the time of writing the visitor counter on my blog had crossed 5.5 million. The future of publishing is exciting particularly with neural computing transforming the translation landscape and making literature from different cultures rapidly available. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is being experimented with to create short stories. Technological advancements such as print-on-demand are reducing warehousing costs, augmented reality is adding a magical element to traditional forms of storytelling, smartphones with processing chips of 8GB RAM and storage capacities of 256GB seamlessly synchronised with emails and online cloud storage are adding to the heady mix of publishing. Content consumption is happening on electronic devices AND print. E-readers like Kindle are a new form of mechanised process, which are democratizing the publishing process in a manner seen first with Gutenberg and hand presses, and later with the Industrial Revolution and its steam operated printing presses.

The future of publishing is crazily unpredictable and incredibly exciting!

3 Feb 2019

Every Monday I post some of the books I have received in the previous week. This post will be in addition to my regular blog posts and newsletter.

In today’s Book Post 23 included are some of the titles I received in the past few weeks and are worth mentioning and not necessarily confined to parcels received during the holiday season.

Enjoy reading!

7 January 2019

Recently the Rs 25 lakh JCB Prize for Literature was announced. It is not the first literary prize in India nor is it the first of such a large value. Before this the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature offered a cash prize of $50,000 which was drastically cut by 50% to $25,000 in 2017. The generous JCB Prize will focus on a distinguished work of fiction and consider translations too. Self-published works will not be eligible. Authors must be Indian citizens. The longlist of ten will be announced in September, and a shortlist of five in October, with the winner to be declared at an awards ceremony on November 3. Each shortlisted author will receive Rs 1 lakh ($1500). The winning author will receive a further Rs 25 lakhs (approx. $38000). An additional Rs 5 lakhs ($7700) will be awarded to the translator if the winning work is a translation.

The Literary Director is award-winning author Rana Dasgupta. The advisory council consists of businessman Tarun Das (Chairperson), Rana Dasgupta, art historian Pheroza Godrej, award winning writer Amitava Ghosh and academic and translator Prof. Harish Trivedi. The jury for 2018 consists of filmmaker Deepa Mehta (Chairperson), novelist and playwright Vivek Shanbhag, translator  Arshia Sattar, entrepreneur and scholar Rohan Murty, and theoretical astrophysicist and author Priyanka Natarajan.

Arshia Sattar, entrepreneur and scholar Rohan Murty, and theoretical astrophysicist and author Priyanka Natarajan.

To formally announce the prize an elegant launch was organised at The Imperial, New Delhi on 4 April 2018 where the who’s who of the literary world gathered. It was by invitation only. Those who spoke at the event were Lord Bramford, Chairman, JCB, and Rana Dasgupta, Literary Director. Lord Bramford spoke of the fond memories he had of his travels through India in the 1960s. Rana Dasgupta underlined the fact that most of the prestigious literary awards are not always open to Indian writers and especially not for translations, a gap that the JCB Prize wishes to address. He also announced a tie-up with the Jaipur Literature Festival (details to be announced later). In fact, all three directors of JLF were present – Namita Gokhale, William Dalrymple and Sanjoy Roy.

Namita Gokhale, writer and publisher; Rajni Malhotra, books division head, Bahrisons with Jaya Bhattacharji Rose, International publishing consultant

Literary awards are very welcome for they always have an impact. They help sell books, authors are “discovered” by readers and the prize money offers financial assistance to a writer. Prizes also influence publishers’ commissioning strategies. The biggest prize in terms of its impact factor are the two prizes organised by the Man Booker – for fiction and translation.

Recognising the importance of financial security for a writer Lord Bramford told the Indian Express “Money often is a good motivator…Creative people like writers or artists often don’t get much reward. And we wanted to reward them.” This is borne out by award-winning writer Sarah Perry who wrote in The Guardian recently about winning the East Anglian book of the year award in 2014, it gave her not only legitimacy for her work but enabled her to afford a better computer to write upon; she “felt suddenly at ease. … I felt like an apprentice carpenter given the tools of the trade by a benevolent guild.” Poet and novelist Jeet Thayil too echoed similar feelings on stage when he won the $50,000 DSC Prize in 2013 for Narcopolis. Just as novelist Jerry Pinto did when he won the 2016 Windham-Campbell Prize of $150,000.

Ira Pande, editor and translator; Diya Kar, publisher, HarperCollins India with professor Harish Trivedi, member, Advisory Council, The JCB Prize for Literature

Lord Bamford, Chairman of JCB; Neelima Adhar, poet and novelist, Arvind Mewar, 76th custodian of Mewar dynasty

The JCB Prize for Literature is a tremendous initiative! It will undoubtedly impact the Indian publishing ecosystem. If publishers do not have eligible entries to send immediately particularly in the translation category, they will commission new titles. The domino effect this action will be of discovering “new” literature in translation and encouraging literary fiction by Indian writers, which for now is dwindling. By making literature available in English and giving it prominence there has to be a positive spin-off especially in terms of increased rights sales across book territories and greater visibility for the authors and translators.

( Pictures used with permission of the JCB Prize for Literature)

3 May 2018

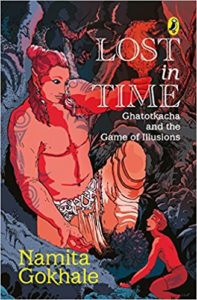

Lost in Time: Ghatotkacha and the Game of Illusions is Namita Gokhale’s first young adult novel, published by Puffin India but not her first publication for children – a few years ago she published the hugely successful Puffin Mahabharata.

Lost in Time: Ghatotkacha and the Game of Illusions is Namita Gokhale’s first young adult novel, published by Puffin India but not her first publication for children – a few years ago she published the hugely successful Puffin Mahabharata.

Lost in Time: Ghatatkacha and the Game of Illusions is the story told in the voice of young Chintamani Dev Gupta who is sent packing to a birding camp near Sat Tal lake. Chintamani, AKA Chintu Pintu, is inexplicably transported to the days of the Mahabharata. Trapped in time, he meets Ghatotkacha and his mother Hidimbi. The gentle giant, a master of illusions and mind boggling Rakshasa technology, wields his strength with knowledge and wisdom, and imparts the age old secrets of the forest and the elemental forces. In his company, Chintamani finds himself in the thick of the most enduring Indian epic – the Mahabharatha. A tender look at a remarkable friendship as well as the abiding riddles of time , this visual treat of a book casts light on the first born son of the Pandavas, – one who finds rare mention in the fading pages of myth and legend. But there’s more to the story. Aided by Dhoomavati, the mistress of smoke and secrets, Chintamani returns to his own time – our time – and urban life in Gurgaon, AKA Gurugram. The rhythm of modern urban life, and his passion for football, cannot erase the memories of his incredible encounter with the past, and his friendship with Ghatotkacha which defies the barriers of time.

urban life, and his passion for football, cannot erase the memories of his incredible encounter with the past, and his friendship with Ghatotkacha which defies the barriers of time.

It is a lovely book about a minor but significant character of the Mahabharata. Namita Gokhale in her story has told the story tenderly, focusing not just on the legend of Ghatotkach but placing it well within the context of the major episodes of the epic. Yet there are two elements in the book that are baffling. One is the illustration of Ghatotkach. According to legend he is given the name that he has because of his bald pate shaped like a ghada/ an urn. Yet the illustrations on the book cover and accompanying the text show him to have beautiful long hair. The second was the promotion for the Puffin Mahabharata written by Namita Gokhale ten years ago. Chintamani after returning to modern India is intrigued by the epic and goes to his bookshelf to locate it. He recalls his mother buying this particular version of the epic and then proceeds to quote the book blurb. Curious way of promoting the previous book given it has already been mentioned in the opening pages of Namita Gokhale’s publications.

All said and done it is a beautifully written book especially the stunning passages of the milky way, playing with the sunlight and weaving a hammock out of cobwebs. Absolutely gorgeous!

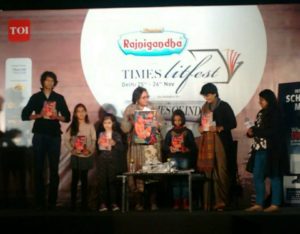

On Sunday, 26 November 2017, at the Times of India LitFest, New Delhi, Namita Gokhale’s book was launched. After which I was in conversation with her. Watch the event here:

28 Nov 2017