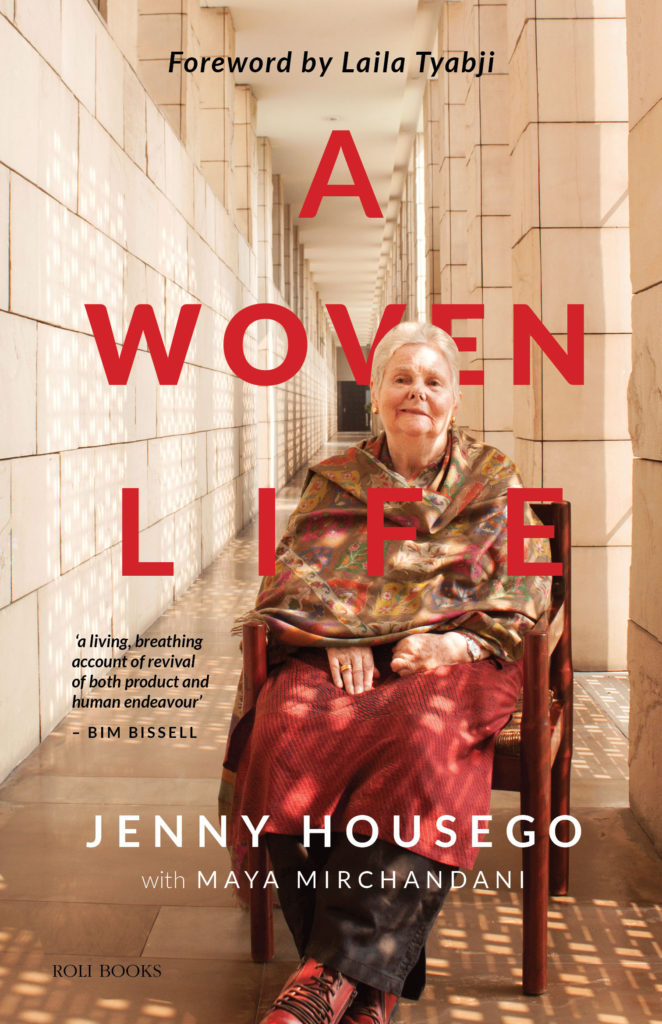

“A Woven Life” by Jenny Housego

Memoirs, autobiographies and biographies are a great introduction to a life. They also share a period through personal stories making history come alive. Memoirs are mostly a great story told from one person’s perspective — “my story”. As Eric Idle says to John Cleese while discussing the latter’s memoir in a public conversation, “well it is very hard to write about yourself” but a memoir is also only a slice of history or what you choose to tell.

In textile historian, entrepreneur and collector Jenny Housego discusses her childhood in England, her marriage to journalist David Housego and her passion for textiles that was ignited during her stint at V&A, London. She developed a fascination for “Anatolian carpets of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries … [she wanted to show in her research] that the so-called early Egyptian carpets had actually been made in Anatolia and displayed many examples of early Christian and Byzantine art which seemed to me to bear close similarities to the designs on these carpets.” Her husband, David, was soon posted to Iran, Afghanistan and later India. She accompanied him and sometimes on the tours he undertook. Along the way her love for textiles deepened. On her travels she was able to collect exquisite samples. When she came to India she developed an interest in the paisley designs of Kashmiri shawls. It sparked a lifelong love for the handloom. Jenny Housego managed to convert her keen interest in Indian handlooms into a successful business. At first she set up a company with her then husband, David Housego, called Shades of India. Subsequently when her marriage fell apart she set up another one — Kashmir Loom. This time focussing specifically on her interest for handlooms from Kashmir.

A Woven Life has been co-authored by Maya Mirchandani as Jenny Housego’s left side is paralysed due to a stroke she suffered some years ago. It is a memoir that is easy to read. It has tiny illuminating details that only reinforce how good art combined with talent can survive through the ages. For example, Jenny Housego’s granduncle was the famous American painter, John Singer Sargent. In one of his portraits uses a Kashmiri paisley shawl woven in India. Jenny Housego spotted it in the painting while searching for antique shawls whose motifs she could incorporate in the Kashmir Loom design library. She decided to find out if the shawl still existed. Sure enough. It did. She sent the image to Warren Adelson, a friend

and well-known art dealer in New York who specialized in Sargent paintings. The shawl had been used as a regular prop in many of Sargent’s paintings but he had decided to gift it to one of his clients. Incredibly the shawl was now owned by a British peer, Lord Cholmondeley, who kept it at his stately home.

Presumably, Sargent must have painted an ancestor of the lord’s wife with the shawl wrapped around her and then must have given it to her. Warren wrote to him on my behalf and his Lordship kindly agreed to bring it to London for me to see. In the hallway of his Mayfair home on a cold, dark rainy day, the shawl was brought to me and placed on a table. The hallway was badly lit and no one offered to hold it up for me to photograph properly. I remember draping it over a side table as well as I could, then my flash failed. The wool was coarse, clearly woven from local sheep, not pashmina at all, but the shawl was exquisite in spite of the rough wool. It had been looked after well. Woven using the technique called ‘kani’ for which Kashmir is renowned, it had patterns on a large border and on either end of the shawl were big paisleys in shades of blue with accents of kashmir loom: stepping out of another’s shadow reds and pinks. Each paisley was made up of tiny leaves and flowers woven to form the shape. Above the main border was another row of much smaller paisleys woven the same way, but set at an angle, slanting to the right. The outer border at the very end of the paisleys wrapped around the entire shawl like a vine of tiny blue-green leaves. Bent over it in that dark hallway, I knew I had to try and recreate it. I didn’t know if it would work, but I was certain it would become Kashmir Loom’s signature item if it did.

Her life with David Housego had very interesting moments. For instance, they were living in Iran in the period before the revolution, so the shift in sentiments from the Shah to the Ayatollah were palpable. Then as a prominent foreign correspondent, David Housego, had access to many sensitive stories. For instance, David had written in the Economist, saying that the Iranians were building a naval base at Chabahar on the eastern side of the Gulf coast. Husband and wife journeyed to Chabahar where the Iranian government representatives denied the existence of such a base until a night watchman who had obviously not briefed by the officials confirmed that David’s report was correct. Another terrifying moment is Jenny Housego’s account of David and her younger son, Kim’s, abduction by militants in Kashmir. Kim was taken away from his parents in Srinagar and there was no trace of him for seventeen days. Given that David was a well-known British correspondent based in South Asia, he knew relevant people across the subcontinent. These included politicians, diplomats, journalists etc. As a result, according to Jenny’s memoir, David was able to keep the pressure on the militants since he had activated all the channels and would hold regular press conferences. David too mentions the abduction of Kim in an article he published in 2011. ( David Housego, “An Indian Journey“, Seminar, 2011.)

A Woven Life has two very distinct narratives embedded in it. One is Jenny Housego’s passion for textiles particulary Kashmiri weaves. The second is her life with David Housego. In fact it was David who inadvertantly set her off on this journey of textiles by encouraging her to apply for a job as a museum assistant at the Victoria and Albert Museum ( V&A) in London. She was apprenticed to Dr May Beattie, a leading scholar of her time in

Oriental rugs and carpets. It obviously ignited a passion that Laila Tyabji, Chairperson, Dastkar, recognised upon meeting Jenny Housego for the first time. She recalls it in her foreword to the book:

... we settled down to watch her slide presentation of the Punja durries’ documentation and out came the second side of Jenny! Behind the diffident, very British, understated, rather shy exterior was an insightful, academically trained mind; the scholarship coupled with a passionate excitement about her subject. …I still remember Jenny’s illuminating exposition of ‘interlocking circles’ and how so many motifs and designs are based on combinations of this. After that I saw interlocking circles everywhere – on Etruscan mosaics, Celtic stone carving, Mughal jaali lattice work, Kutchi ajrakh block prints, rococo wrought iron, Indonesian wax resist batiks.

Despite her marriage falling apart after thirty years, Jenny Housego is unable to recount incidents in her memoir without mentioning David regularly. She comes across as bitter while talking about his non-existent parental duties when their sons were toddlers. Having said that David was an integral part of her life and to a large extent seems to have given her the opportunities to pursue her interests in textiles. In the book trailer for A Woven Life there are lovely snapshots recorded from Jenny Housego’s life, many of them are of the Housegos as a happy family — a bit at variance from what the text portrays. Regretfully it does not have sufficient details about textile histories and Kashmiri handlooms. The book would have been richer by offering more detailed insight into these traditional forms of weaving. Nevertheless A Woven Life is a quick read.

PS I read an advance proof of the book, given the current lockdown due to the Covid19 healthcare crisis. Sadly, it did not have a single photograph. But I am assured by the marketing team that the print edition will have photographs accompanying the text.

4 May 2020