“Publishing Pangs”,Economic Times, Sunday Edition, 5 July 2020

On 24 March 2020 invoking the Disaster Management Act (2005) the first phase of the lockdown to manage the Covid-19 pandemic was announced. “Disaster Management” is considered to be a part of the Concurrent List under “social security and social insurance”. With the announcement all but the most essential economic activity halted nationwide. Only 4 hours’ notice was provided, insufficient time to plan operations.

Demand and supply existed but all cash cycles dried up — because bookstores were not operating. Brick-and-mortar stores had to close while online platforms focused on delivering only essential goods and books were not on the list. Priyanka Malhotra says “When Full Circle reopened in mid-May, there was a great demand for books. Mid-June, supply lines are still fragile, so getting more books regularly is uncertain. Well-stocked warehouses are outside city limits and are finding it difficult to service book orders to bookstores. We are mostly relying on existing stocks.”

In future, the #WFH culture will remain particularly for editors, curation of lists, smaller print runs, the significance of newsletters will increase, exploring subscription models for funding publishers in the absence of government subsidies and establishment of an exclusive online book retailing platform such as bookshop.org. Introducing paywalls for book events as the lockdown has proven customers are willing to pay for good content. Distributors and retailers will take less stock on consignment. Cost cutting measures will include slashing travel as a phone call is equally productive, advances to authors will fall, streamlining of operations with leaner teams especially sales teams as focused digital marketing is effective, With the redefining of schools and universities due to strict codes of physical distancing and cancellation of book fairs, publishers will have to explore new ways of customising, delivering and monetising content.

In such a scenario the importance of libraries will grow urgently. Libraries benefit local communities at an affordable price point. They are accessed by readers of all ages, abilities and socio-economic classes for independent scholarship, research and intellectual stimulation. The nation too benefits with a literate population ensuring skilled labour and a valuable contribution to the economy. By focusing upon libraries as the nodal centre of development in rehabilitation and reconstruction of a nation especially in the wake of a disaster, the government helps provide “social security and social insurance”. Libraries can be equipped without straining the limited resources available for reconstruction of a fragile society by all stakeholders collaborating. As a disaster management expert said to me, “Difficult to find a narrative for what we are going through”.

After a disaster, the society is fragile. It has limited resources available for rehabilitation and reconstruction. To emerge from this pandemic in working condition, it would advisable for publishers to use resources prudently. It is a brave new world. It calls for new ways of thinking.

Given this context, the Economic Times, Sunday Edition published the business feature I wrote on the effect of the pandemic on the publishing sector in India. Here is the original link on the Economic Times website.

***

As the first phase of the sudden lockdown to manage the Covid-19 pandemic was declared on March 24, the timing was particularly unfortunate for the books publishing industry. End-March is a critical time in the book publishing industry.

End-March is a critical time in the book year cycle. It is when accounts are settled between distributors, retailers and publishers, enabling businesses to commence the new financial year with requisite cash equity. Institutional and library sales are fulfilled. The demand for school textbooks is at its peak. But with the lockdown, there was a severe disruption in the production cycle — printing presses, paper mills, warehouses and bookshops stopped functioning. Nor were there online sales as books are not defined as essential commodities.

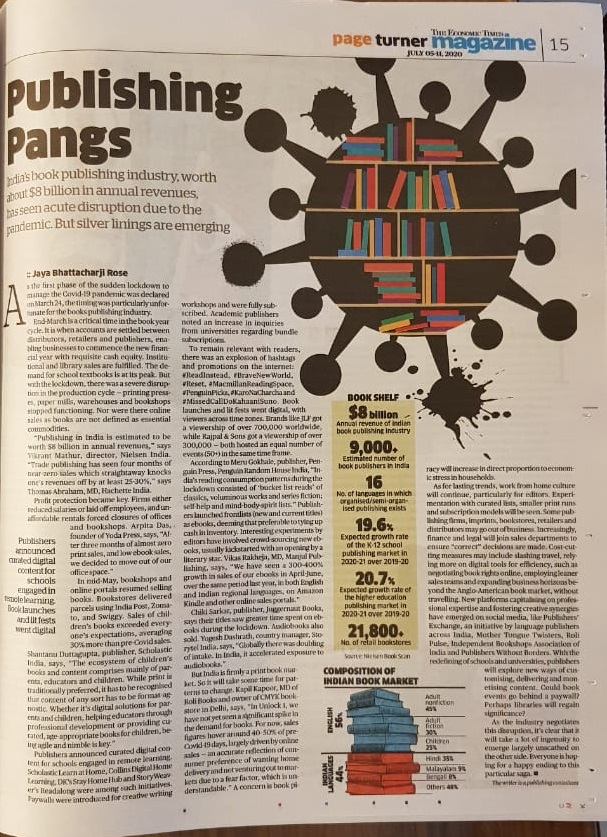

“Publishing in India is estimated to be worth $8 billion in annual revenues,” says Vikrant Mathur, director, Nielsen India. “Trade publishing has seen four months of near-zero sales which straightaway knocks one’s revenues off by at least 25-30%,” says Thomas Abraham, MD, Hachette India.

Profit protection became key. Firms either reduced salaries or laid off employees, and unaffordable rentals forced closures of offices and bookshops. Arpita Das, founder of Yoda Press, says, “After three months of almost zero print sales, and low ebook sales, we decided to move out of our office space.”

In mid-May, bookshops and online portals resumed selling books. Bookstores delivered parcels using India Post, Zomato, and Swiggy. Sales of children’s books exceeded everyone’s expectations, averaging 30% more than pre-Covid sales. Shantanu Duttagupta, publisher, Scholastic India, says, “The ecosystem of children’s books and content comprises mainly of parents, educators and children. While print is traditionally preferred, it has to be recognised that content of any sort has to be format-agnostic. Whether it’s digital solutions for parents and children, helping educators through professional development or providing curated, age-appropriate books for children, being agile and nimble is key.”

Publishers announced curated digital content for schools engaged in remote learning. Scholastic Learn at Home, Collins Digital Home Learning, DK’s Stay Home Hub and StoryWeaver’s Readalong** were among such initiatives. Paywalls were introduced for creative writing workshops and were fully subscribed. Academic publishers noted an increase in inquiries from universities regarding bundle subscriptions.

To remain relevant with readers, there was an explosion of hashtags and promotions on the internet: #ReadInstead, #BraveNewWorld, #Reset, #MacmillanReadingSpace, #PenguinPicks, #KaroNaCharcha and #MissedCallDoKahaaniSuno. Book launches and lit fests went digital, with viewers across time zones. Brands like JLF ( Jaipur Literature Festival) got a viewership of over 700,000 worldwide*, while Rajpal & Sons got a viewership of over 300,000 — both hosted an equal number of events (50+) in the same time frame.

According to Meru Gokhale, publisher, Penguin Press, Penguin Random House India, “India’s reading consumption patterns during the lockdown consisted of ‘bucket list reads’ of classics, voluminous works and series fiction; self-help and mind-body-spirit lists.” Publishers launched frontlists (new and current titles) as ebooks , deeming that preferable to tying up cash in inventory. Interesting experiments by editors have involved crowd-sourcing new ebooks, usually kickstarted with an opening by a literary star. Vikas Rakheja, MD, Manjul Publishing, says, “We have seen a 300-400% growth in sales of our ebooks in April-June, over the same period last year, in both English and Indian regional languages, on Amazon Kindle and other online sales portals.”

Chiki Sarkar, publisher, Juggernaut Books, says their titles saw greater time spent on ebooks during the lockdown. Audiobooks also sold. Yogesh Dashrath, country manager, Storytel India, says, “Globally there was doubling of intake. In India, it accelerated exposure to audiobooks.”

But India is firmly a print book market. So it will take some time for patterns to change. Kapil Kapoor, MD of Roli Books and owner of CMYK bookstore in Delhi, says, “In Unlock 1, we have not yet seen a significant spike in the demand for books. For now, sales figures hover around 40–50% of pre-Covid-19 days, largely driven by online sales — an accurate reflection of consumer preference of wanting home delivery and not venturing out to markets due to a fear factor, which is understandable.” A concern is book piracy will increase in direct proportion to economic stress in households.

As for lasting trends, work from home culture will continue, particularly for editors. Experimentation with curated lists, smaller print runs and subscription models will be seen. Some publishing firms, imprints, bookstores, retailers and distributors may go out of business. Increasingly, finance and legal will join sales departments to ensure “correct” decisions are made. Cost-cutting measures may include slashing travel, relying more on digital tools for efficiency, such as negotiating book rights online, employing leaner sales teams and expanding business horizons beyond the Anglo-American book market, without travelling. New platforms capitalising on professional expertise and fostering creative synergies have emerged on social media, like Publishers’ Exchange, an initiative by language publishers across India, Mother Tongue Twisters, Roli Pulse, Independent Bookshops Association of India and Publishers Without Borders. With the redefining of schools and universities, publishers will explore new ways of customising, delivering and monetising content. Could book events go behind a paywall? Perhaps libraries will regain significance?

As the industry negotiates this disruption, it’s clear that it will take a lot of ingenuity to emerge largely unscathed on the other side. Everyone is hoping for a happy ending to this particular saga.

* At the time of writing the article, this figure of 700,000+ held true for JLF. But on the day of publication of the article, the number has far exceeded one million.

** Storyweaver’s Readalong are multilingual audio-visual storybooks.

5 July 2020