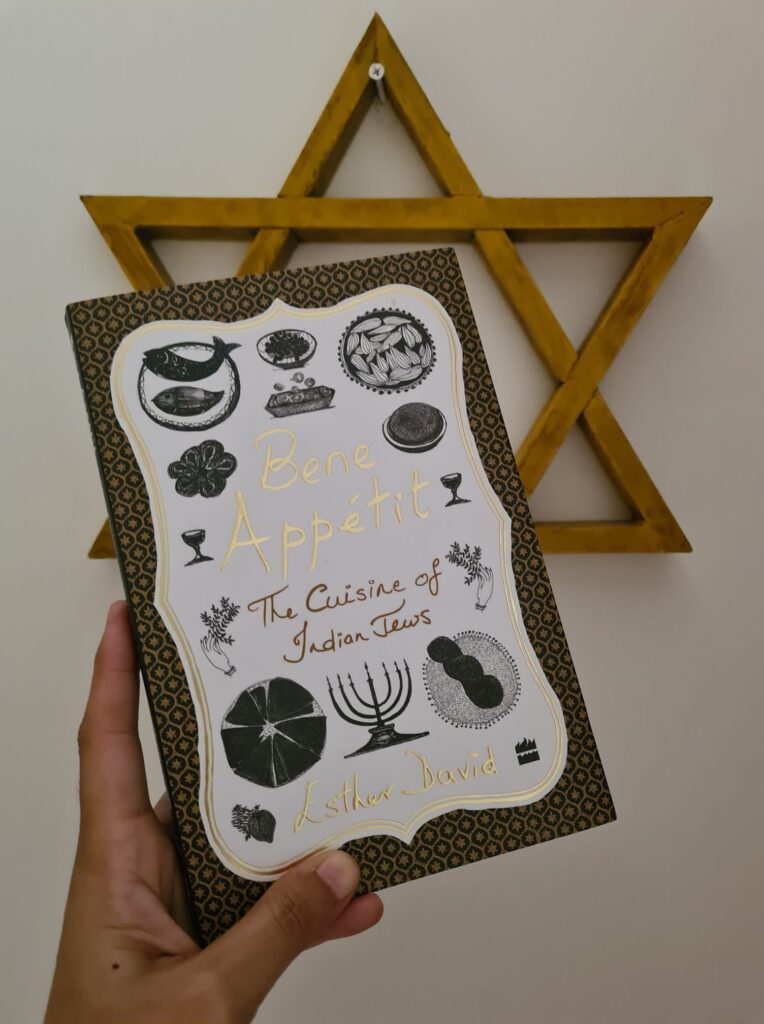

“Bene Appetit” by Esther David

Award-winning Indian Jewish author and illustrator Esther David was awarded the Hadassah Brandeis Reserach Award (USA) for studying Indian Jewish cuisine. In India, Jews first settled in Kerala before the Christian Era began. These are the Cochin Jews. In the late eighteenth century, the Bene Israel Jews arrived in western India, settling along the coast in areas like Alibaug and Mumbai. The Baghdadi Jews first settled in coastal Surat, then moved towards Mumbai and Kolkata. The Bene Ephraim Jews chose the seashores of Andhra Pradesh, while the Bnei Menashe Jews of Mizoram and Manipur.

Esther David’s Bene Appetit is part-travelogue and a detailed recipe book, collating recipes from different parts of the country. She discovers that despite having set their roots in India, many centuries ago, Indian Jews abide by the strict dietary rules that govern Judaism. The Jews have adopted locally available produce in their recipes and to some degree adapted the dishes to their tastes. Jews insist upon kosher meat, a strict demarcation between meats and milk, eating fruits after their meals, making unleavened bread, consuming only certain kinds of fishes, avoiding shellfish etc. Esther David has meticulously documented her search for recipes, meeting people, being introduced to strangers who spontaneously welcomed her warmly into their homes and serving strict Jewish fare.

David discovers the immense variety that exists in Jewish cuisine. Indian Jews have readily substituted milk with coconut milk. They also use plenty of rice-based dishes, jaggery, some of the local herbs and spices such as gongura leaves in Andhra Pradesh and panch phoran in West Bengal. Fruits of all kinds are used after meals or even to make the sherbet to offer at religious occasions.

This is a seminal book for its documentation of a dying culture in India. The Jewish population is dwindling. At the time of Indepence (1947) there were approximately 50,000. Today, there are few left as many have emigrated to Israel. So much so that at times it gets difficult to have a quorum of ten Jewish men or a miniyan to fulfil certain religious obligations. There are other signs of the community disappearing. For instance, local bakeries that made unleavened bread for Shabbath, no longer do so. Cloths used for religious ceremonies are not easily available locally any more. So are brought from Israel by relatives or visitors. Time-consuming dishes like malida are made on exceptional occasions. The Jews now simply use chapatis or a similar bread as it is technically unleavened too. Hence, “Bene Appetit” is a critical repository of socio-cultural practices. Future generations will appreciate this book.

Apart from Jews, anyone interested in experimenting with new recipes, reading cookery books and seeking healthy alternatives, may find this book useful. Even Hindus who are looking for satvik recipes, will find Bene Appetit very useful to consult. Most often the recipes provided are fairly easy to comprehend but there are some recipes that required careful editing. Even experienced cooks may get mildly confused by the manner in which instructions have been given. For example, the recipes for Pastel and Pastillas seem to have repeated their instructions. It is a bit of a fog. There is another unexpected editorial glitch when David visits the synagogue in Mizoram, she observes that the prayer book was in Mizo but the “words were spelled out in English”. It is well-known that the languages of northeast India did not have a script till recently. This is an oral tradition and it is after 1947 that the languages began to require a script and the Roman script was quickly utilised. It is the same script used for the English language. Save for these minor hiccups, “Bene Appetit” is a stupendous addition to any cookery shelf. I would put it in the same league as the late fashion designer Wendell Rodericks “Poskem”, where he shared recipes from Goan Catholics and those that he recalled from his childhood. These books bring out the beautiful diversity in India that has thrived over centuries.

Note: The photograph of the book has been taken against a wooden Star of David that used to hang in my husband’s childhood home. Jacob’s maternal grandfather was an Afghan Jew who used to often travel to India with his brothers. They use to trade in jewels. But little is known about them. Jacob’s grandfather married a local Christian girl and settled in central India. The only signs of influence his faith left upon his descendants are in these symbols, occasional visits to the local synagogue to meet the rabbi and observing a few Jewish dietary laws. No more. The descendants are practising Christians. Yet, it is fascinating to watch at close quarters the assimilation of Judaism into Jacob’s family. BTW, the Afghan Jews are not mentioned in “Bene Appetit”.

17 April 2021