Vera Michalski-Hoffman’s keynote address at Jaipur Bookmark, 25 Jan 2019

The Jaipur Bookmark is a business conclave held during the Jaipur Literature Festival. In fact it begins a day before the litfest is inuagurated. It is a fantastic space for publishing professionals to congregate from around the world and discuss new trends and share ideas and experiences. On the third day of the conclave, Friday 25 Jan 2019, I moderated a session on “Indies vs Giants”. The scope of the discussion was: “Independent publishers with lower overheads are finding their niche position in the publishing industry around the world, even as publishing giants are consolidating their positions. This session talks about creative risk taking and the tools brave, new publishers adopt.” The panellists were publishers Vera Michalski-Hoffman (Libella group), Karthika VK ( Westland/Amazon), Jeremy Trevathan (Macmillan), and Anna Solding (Midnight Sun Publishing). Vera Michalski-Hoffman also delivered the keynote address and with her kind permission it is reproduced here.

*******

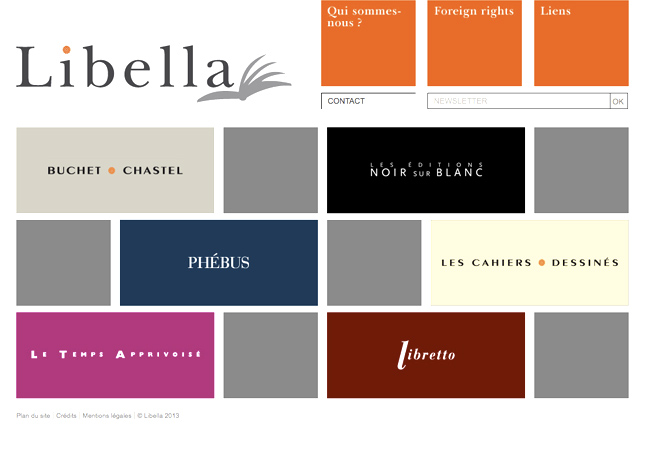

Born in Basel, Switzerland, in a family with Swiss, Russian and Austrian roots, Vera Michalski-Hoffmann spent her childhood in France, studied in Spain and has a degree in Political Science from the Graduate institute of International Studies in Geneva. She established a foundation named after her late husband, The Jan Michalski Foundation for Literature and Writing to actively support literary activities in different countries. She is now the publisher of the Libella group that comprises the following imprints: In France: Buchet/Chastel, Phébus, Le temps apprivoisé, les Cahiers dessinés, Libretto. In Switzerland: Noir sur Blanc, with a new line called Notabilia, Editions Favre. And in Poland: Oficyna Literacka Noir sur Blanc. She also acquired The Polish Bookshop in Paris.

Vera Michalski’s tremendous work in supporting literature with the establishment of Libella group and it’s acquisitions of fine independent publishing firms have ultimately benefitted the fine stable of authors as is noticeable with World Editions and it’s recent expansion plans. “The group is unique in its total financial independence and the diversity of its editorial production: French and foreign literature, travel stories, essays, documents, music, ecology, illustrated books and creative hobbies. Priority is given to quality, especially to the quality of writing.”

*********

I thought that I would focus my speech on the specificities of Libella, being neither a giant nor obviously an Indie so that this case study of an untypical small publishing house evolving into a publishing group publishing in 3 different languages could form a sort of starting point for our discussion.

Let me tell you the story of how this independent group came into existence by a succession of launching new imprints and acquiring existing ones and what fields it covers now, naturally mentioning the Indian or Jaipur connection when appropriate. Forgive me for not respecting a strict chronology for it is a complicated story unfolding in different territories.

The whole story started in 1987 in Switzerland when my husband and I opened les éditions Noir sur Blanc, a niche publisher aiming at bringing mostly Polish and Russian authors to the French-speaking market (France, Belgium, Quebec, Switzerland) and covering both fiction and non-fiction. This was before the fall of the Berlin Wall so not that obvious. Later we covered other fields, like narrative history and published quite a few Jaipur regulars such as William Dalrymple, Giles Milton, or Anthony Sattin. We now bring out as well illustrated books mainly about drawing and photography. A total of over 400 titles.

We soon decided that it was important to publish in Polish as well and opened a Polish branch in 1989 where we started by introducing famous international authors into Poland that were then still unpublished. Charles Bukowski, Henry Miller, Paul Auster, to name just a few. We published Umberto Eco’s novels and brought out detective stories with a travel angle. The likes of Donna Leon, Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, and Andrea Camilleri were unknown then. We have published so far well over 500 books in Polish.

Still in Poland but later, in 2002, Wydawnictwo Literackie, one of the most literary publishing houses founded in 1953 under communist rule and still state owned, came up for sale in the frame of privatization. We stepped in. That magnificent company’s list and backlist never cease to amaze me. Let’s mention just a few names: Margaret Atwood, Jorge Luis Borges, Claudio Magris, Alice Munro, and Orhan Pamuk. Not to mention the best of Polish literature with names such as Olga Tokarczuk, recent winner of the Man booker International,Witold Gombrowicz, or Szcepan Twardoch.

In the year 2000, in Paris, we had acquired Buchet/Chastel, a literary publisher established in 1929, a well-regarded publisher of fiction. This allowed us to touch French literature which we were very keen to do, alongside some significant international authors. Buchet had been the publisher of Malcolm Lowry, Lawrence Durrell, or Henry Miller to mention just a few names. However, in 2000, Buchet /Chastel was well past its glory. People called it “La belle endormie” in reference to the famous tale Sleeping Beauty by Charles Perrault, but remembered the iconic bright orange covers.

It made for a real challenge to bring it back to the forefront of literary life. We hired editors for the different lines we wanted to exist: French literature, world literature, non-fiction. We then took a good look at the impressive backlist and decided what directions we wanted to keep. The founder of Buchet /Chastel, Edmond Buchet was a keen musician and a rather good pianist. He had made friends with a number of famous musicians among them Yehudi Menuhin. He published quite a few books about music. We decided to maintain that line. We opened new fields and started an environmental series. France was then not very receptive to these topics, the field being covered mostly by very politicized books on the verge of pamphlets, on marginal topics. Nobody was focusing on important issues and providing objective material, food for thought so to speak, which we aimed at doing. We decided as well to keep the famous orange covers that people remembered modernizing them by using a different cover paper and different typo. Because we all know that we should not throw out the baby with the bath water! Sometimes there needs to be a sort of continuity. Over the years, we published quite a few Indian writers, in fiction and non-fiction, among them our biggest success was Tarun Tejpal, (The Alchemy of Desire). Our list boasts as well with Aravind Adiga (The White Tiger), Suketu Mehta, Rana Dasgupta, Gurcharan Das, Pankaj Mishra etc.

Shortly before 2000, we had acquired les éditions Phébus, a house founded in 1978, with an excellent reputation especially in foreign literature and stories of great explorers, or rediscovered classics, as Alexandre Dumas’s Le Chevalier de Saint Hermine. Phébus had created a paperback imprint a few years before under the name Libretto, now a very important part of the Libella group.

In 2003 we opened a brand new field, drawing, and started publishing big format soft cover beige albums typeset in a classical elegant way and printed on quality paper under the name Les Cahiers dessinés. The aim was to bring back drawing to its rightful place as one of the important disciplines of art alongside painting or sculpture. We now have more than 100 titles in our backlist and some books sold quite well, like Alberto Giacometti’s Paris Without End.

Photography is represented in the Libella group by 2 imprints: Photosynthèses which was started from scratch in 2013 in Arles, in the south of France, (the first book published in 2014 was Lou Reed’s Rhymes). Every book is considered unique and different formats co-exist in the list. They are printed with the utmost care. Libella acquired editions Robert Delpire, founded in 1951, when the founder chose to retire a few years ago. We are gradually opening the list to new authors while remaining careful not to alter the excellent image the house has enjoyed in the past with famous authors such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Josef Koudelka, or Robert Franck. Under these new circumstances, we reacted quickly when the gallery adjoining the Delpire office became available. We relabeled it FOLIA, a name that seemed to reconcile book and image, and produce now 5 exhibitions a year showing both our authors’ work and others whose work fits into the concept. The aim is to show photography with a literary angle.

Another line in Libella needs to be mentioned, practical books under the imprint Le Temps apprivoisé, a part of Buchet Chastel when we acquired it. We decided to keep it in spite of a relative distance to the main part of the catalogue and a sector fragilized by the competition with internet sites and cheap books produced by the giants able to have huge print runs.

One recent development is very important to me. In 2016, World Editions joined Libella and we now publish in English a small list of 8 books a year under the motto Voices from around the globe. The office is in Amsterdam. The idea is to help interesting books, often from peripheral languages, to get access to translations and the world market in an age where translations, expensive as they are, tend to stick to mainstream authors and main languages leaving some authors alone.

In between, in 1991, we had intervened in order to prevent the closing of the Polish Bookstore established in Paris since 1833.This very well located shop, then selling mostly books in Polish or translated from Polish. It is now a very active general bookstore. It welcomes any kind of literary event in a part of Paris where books have sadly given way to clothes in spite of the fact that it was home to most publishers until recent years saw a consolidation of the industry bringing about the need for bigger office space that the old district of St. Germain des Prés could not offer. This happened recently as a result of the consolidation in the publishing industry, most small literary publishers had to leave the area to move in with their respective groups often located outside the historical centre of town. The bookstore and the gallery became an important part of our publicity and ensure an improved visibility in Paris.

I believe I gave you the general picture of Libella, a confederation of small almost niche mostly literary publishers, publishing in 3 languages out of offices in Lausanne, Paris, Arles, Warsaw, Krakow, Amsterdam and New York.

In spite of our relatively small size, we have a certain complexity, publish over 300 books a year. So where do we stand? Let our discussion clarify that point.

12 Feb 2019