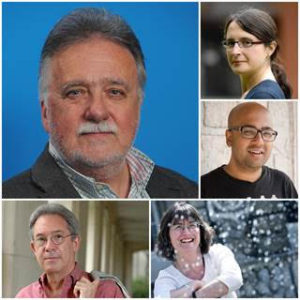

The brave new mediocre: ‘The Testaments’ by Margaret Atwood reviewed by Anil Menon

Anil Menon wrote a fantastic review of Booker winner 2019 Margaret Atwood’s The Testaments for the Hindu. The review was published in print on Sunday, 27 October 2019 and in digital on Saturday, 26 October 2019. Here is the original url. With Anil Menon’s permission I am c&p the text below.

****

A dystopian novel is where the Enlightenment goes to die. Since we’re awash in dystopian novels, perhaps it suggests that far from fearing this eventuality — the onset of a dark age — perhaps we’ve become resigned to it. As Cavafy suggests in his poem, ‘Waiting for the Barbarians,’ for those weary of civilisation, barbarity may even represent “a kind of solution.”

There are two kinds of dystopias. In dystopias of the first kind — represented by Zamyatin’s We, Orwell’s 1984, and their numerous progeny — the prison gates are locked from the outside. This means there’s an inside and an outside; there’s a jailor and the jailed; there are secret messages and secret societies; there are betrayals and breakouts; and at the end, a door is either closed for good or left ever so slightly ajar for a sequel to squeeze through. In dystopias of the second kind — represented by Huxley’s Brave New World — the prison gates are locked from the inside. There’s no need for jailors, because the people have jailed themselves. These novels are much harder to write.

Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) is a dystopia of the first kind, and at the end of the story, she chose to leave the door ajar. Thirty-four years later, the much-awaited sequel, The Testaments, tells the rest of the tale. For those who came in late, a brief recap might help. The Handmaid’s Tale is based on the premise that the U.S. has fragmented into a number of independent republics, and one of the largest fragments — the Republic of Gilead — is now run by a Puritan theocracy.

Unlike Tolstoy’s unhappy families, all theocracies are alike. The men are men; uninformed and uniformed, and uniformly jerks. But women in Gilead come in four basic models: the Aunts, celibate women in charge of female indoctrination; the Wives, who are just that; the Marthas, who do manual labour; and the Handmaids, who are wombs-on-rent. Then there are the whores. Of course, there are no whores in Gilead, just as there was no poverty in the Soviet Union.

This set-up offers a lot of scope for misery, and in The Handmaid’s Tale Atwood used all the fine English at her disposal to depict just how ghastly a world based on the Womb and nothing but the Womb would be. This world is a dystopia not (only) because men have total power over women, but because women have been coerced, persuaded, indoctrinated, habituated into oppressing other women.

It’s clear Gilead is in deep trouble. Their science is Biblical, their society Saudi, their never-ending wars Balkan, and their economics Soviet. Dystopias of the first kind always have lousy economics. Consequently, for all the horror, the reader may relax: it’s only a matter of time. Nonetheless, it seems some readers couldn’t relax. Atwood mentions in the acknowledgements that she wrote The Testaments to answer a persistent query: “How did Gilead fall?” The urge to please readers is always inimical to great literature.

The Testaments is a plot-heavy novel and has three storylines. The first deals with the musings and machinations of Aunt Lydia, the most powerful of the four Founders of Gilead’s Aunt institution; the second with Agnes, the daughter of a powerful Commander in Gilead; and the third with seemingly ordinary Daisy, who lives in Toronto and is being raised by two very nice and seemingly ordinary people. Daisy turns out to be not so ordinary, and her storyline is the usual Hero’s journey. Agnes serves no real purpose other than to illustrate the life of a “privileged” teen in Gilead. Meanwhile, Aunt Lydia serves up info-dumps, while she waits for Daisy to turn up in Gilead and set the republic’s destruction in motion. The last dozen chapters compress everything into summaries, hasty action scenes, and neat resolutions.

Unlike The Handmaid’s Tale, whose protagonist Offred is entirely ordinary, all the key characters in the sequel are exalted in some way. They are important on account of destiny or social role or birth or ability. It’s not just The Testaments’ plot-heavy nature or its disinterest in ordinariness that gives it a genre feel. Atwood has always had an interest in plot. But she is also interested in subtext. The Handmaid’s Tale had a plot — a threadbare one, to be sure, but there was one — and loads of subtext.

In The Testaments, however, there’s virtually no subtext. The meaning is all on the surface. What you see is what you get. Events cause other events, obstacles are external, sections end on cliffhangers, and characters remain unchanged by the plot. In Atwood’s short story ‘Happy Ending’ (now a writing workshop staple used to discourage plot-intensive stories), she remarks that plots are “just one thing after another, a what and a what and a what.” That’s not true, but here, in this novel, it is just that.

The writing is always competent — this is Atwood after all — but it could’ve been written by any competent writer. The Handmaid’s Tale requires one to pause frequently and contemplate, as when Atwood writes of a character who has just entered a room: “He was so momentary, he was so condensed.” Or “Old love; there’s no other kind of love in this room now.” The Testaments offers few such pleasures. At one point, in the middle of a flashback on how the Gilead Republic came to be, Aunt Lydia, bored by the all-too-predictable violence, tells us: “How tedious is a tyranny in the throes of enactment.” So too is a novel in the throes of enacting an unnecessary sequel.

This novel is entertaining enough; a film starring Meryl Streep is sure to follow. It boggles the mind however that the novel was even shortlisted for the Booker, let alone managing to win a share of the prize. Perhaps this is truly the age of the “new mediocre,” as The New York Times fashion critic, Vanessa Friedman, recently said in another context. Brave new mediocre. If we have lost the ability to distinguish a mediocre literary effort from a superlative one, or worse, if we have lost the courage to even acknowledge there is a problem, then it is not corrupt institutions we should fear. It is ourselves. There is no rescuing prisoners who fancy themselves free.

30 October 2019