Fostering a reading culture / Happy Mother’s Day!

(An extended version of this article was published on Bibliobibuli, my blog on Times of India, on Saturday 12 May 2018. Bibliobibuli focuses on publishing and literature.)

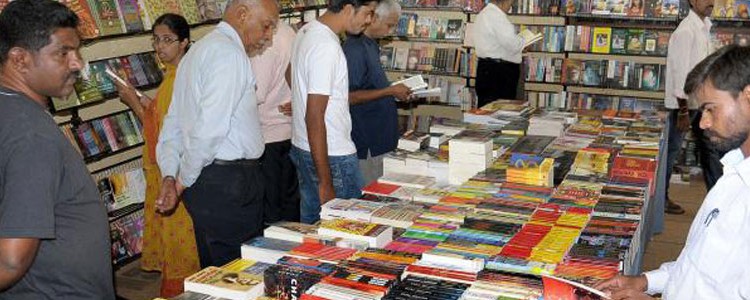

Every Labour Day, the May Day Bookstore & Café holds a big book sale. It consists mostly of second-hand books being sold at reasonable prices and customers flock to the store. This year was no different. Later Sudhanva Deshpande, Managing Editor, LeftWord Books, posted a picture on social media platforms he had taken of a mother holding a tiny pile of books while her daughter stood by watching expectantly. It is a very powerful picture as it works at multiple levels. It is obvious the mother is in charge of her daughter’s education and is keen she learns further. She is the primary force. She is determined to buy the books for her child even though she can ill-afford the small number of books in her hand. The mother had only Rs 10 to pay for the books. She was short of money and unable to pay the billed amount. The unfortunate seemingly admonishing finger in the picture is not really doing what it seems to be doing according to the photographer. The bookshop attendants were telling the mother to take the books away and pay later, whenever she could!

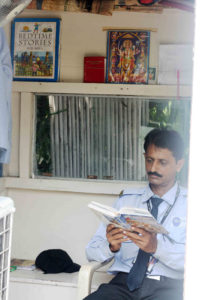

Books are respected all over the world but in India they are revered. Few can afford them and those who can, treasure what they possess. This picture by The Delhi Walla, epitomises it splendidly where the few books owned by the security guard are placed on the same shelf as the portrait of the god. It is understandable that the mother in the picture wishes her daughter to be literate as with it comes respect. For her to be in a bookstore is a path breaking moment. It symbolises the crumbling of a notional barrier of what is traditionally perceived as a popular middle class cultural space — the bookstore. Brick and mortar stores by their very definition tend to be exclusive even if some owners do not desire it to be so. Whereas the reality is that footfalls are restricted to those who are comfortable in these elitist spaces.

This is a sad truth because a thriving reading culture is critical for the well-being of a community and by extension the society. The Scholastic India Kids and Family Reading Report ( KFRR) found that “Parents and children agree by a wide margin that

strong reading skills are among the most important skills children should have.” Undoubtedly reading opens a world of possibilities. When Hollywood actor John Travolta gave an interview to magazine editor Priya Kumari Rana ( Outlook Splurge, November 2015, Vol 6) he recalled reading Gordon’s Jet Flight (1961) as a child. It was about a little boy who took his first flight on a 707. At the time the 707 was the last word in aviation. It triggered an ambition and a dream. Today, Travolta not only is a trained pilot but owns a 707!

Buying books continues to be a dream for many individuals and families across the globe. American country singer Dolly Parton likes to give  away books with her Imagination Library. In Feb 2018 she crossed the 100 millionth book. Writer Jojo Myes has pledged to save UK Charity Quick Reads ( Reading Agency ) from closure by funding its adult literacy programme for the next three years.

away books with her Imagination Library. In Feb 2018 she crossed the 100 millionth book. Writer Jojo Myes has pledged to save UK Charity Quick Reads ( Reading Agency ) from closure by funding its adult literacy programme for the next three years.  Outreach community programmes are critical for fostering a reading culture particularly if access to existing cultural spaces are restricted.

Outreach community programmes are critical for fostering a reading culture particularly if access to existing cultural spaces are restricted.

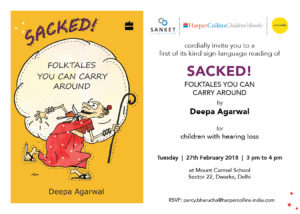

Recently HarperCollins India organised an innovative book launch for children’s author Deepa Agarwal’s Sacked:Folktales You Can Carry Around. It involved a  reading for children with hearing loss. So while the author spoke there was a person standing next to her using sign language to translate what was being said. Recognising this need to foster reading, the nearly 100-year-old firm Scholastic ran a very successful Twitter campaign in India (Sept 2017) where every retweet ensured a book donation to a community library. The publishing firm donated approximately 2000 books. Now they are running a similar campaign for Mother’s Day 2018 (Sunday, 13 May 2018) where a picture uploaded of

reading for children with hearing loss. So while the author spoke there was a person standing next to her using sign language to translate what was being said. Recognising this need to foster reading, the nearly 100-year-old firm Scholastic ran a very successful Twitter campaign in India (Sept 2017) where every retweet ensured a book donation to a community library. The publishing firm donated approximately 2000 books. Now they are running a similar campaign for Mother’s Day 2018 (Sunday, 13 May 2018) where a picture uploaded of  a mother and a child reading will get one lucky family a book hamper.

a mother and a child reading will get one lucky family a book hamper.

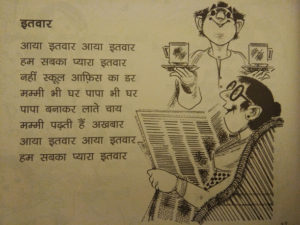

Reading is a social activity. New readers need role models and encouragement. This is captured beautifully in feminist Kamla Bhasin’s nursery rhyme ( available in Hindi and English).

It’s Sunday, it’s Sunday

Holiday and fun day.

No mad rush to get to school

No timetable, no strict rule.

Mother’s home and so is father

Father’s like a busy bee

Making us hot cups of tea.

Mother sits and reads the news

Now and then she gives her views.

It’s Sunday, it’s Sunday

Holiday and fun day.

Noted Karnatik vocalist T. M Krishna in his book Reshaping Art makes an important point where he argues art has to break its casteist, classist and gender barriers and be welcoming to all particularly if cultural landscape has to expand. He asks for the inner workings of the art form to be infused with social and aesthetic sensitivity.

Noted Karnatik vocalist T. M Krishna in his book Reshaping Art makes an important point where he argues art has to break its casteist, classist and gender barriers and be welcoming to all particularly if cultural landscape has to expand. He asks for the inner workings of the art form to be infused with social and aesthetic sensitivity.

T. M. Krishna practices what he preaches. In December 2017 he sang a Tamil sufi song of Nagoor Hanifa which T.M. Krishna performed in a British-era Afghan Church in Colaba, Mumbai. He ended his performance with an invocation to allah in the church. Since then he has done other such performances.

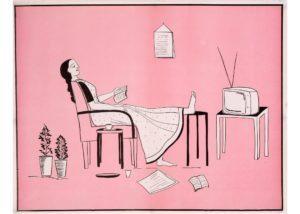

Breaking cultural barriers and making books readily accessible and contributing to the growth of readers is exactly what the publishing ecosystem has to strive for. And as Kamla Bhasin rightly says the personal is political. There is  nothing purely private or public. Every personal act of ours affects society. The act of reading and encouraging their children to read by mothers is not always welcomed in households, even today. Literacy empowers women with ideas, the ability to think and question for themselves, an act that is most often seen as defiance especially within very strongly patriarchal families. This act was captured beautifully in a wordless poster designed many years ago by a Hyderabad-based NGO, Asmita. It shows a woman with her feet up, reading a book, a television set in front of her and the floor littered with open books. Majority of women who see the poster laugh with happiness at the image for the peace it radiates but also at the impossibility of ever having such a situation at home.

nothing purely private or public. Every personal act of ours affects society. The act of reading and encouraging their children to read by mothers is not always welcomed in households, even today. Literacy empowers women with ideas, the ability to think and question for themselves, an act that is most often seen as defiance especially within very strongly patriarchal families. This act was captured beautifully in a wordless poster designed many years ago by a Hyderabad-based NGO, Asmita. It shows a woman with her feet up, reading a book, a television set in front of her and the floor littered with open books. Majority of women who see the poster laugh with happiness at the image for the peace it radiates but also at the impossibility of ever having such a situation at home.

So mothers like the one in the photograph are excellent role models and must be celebrated!

Happy Mother’s Day!

11 May 2018