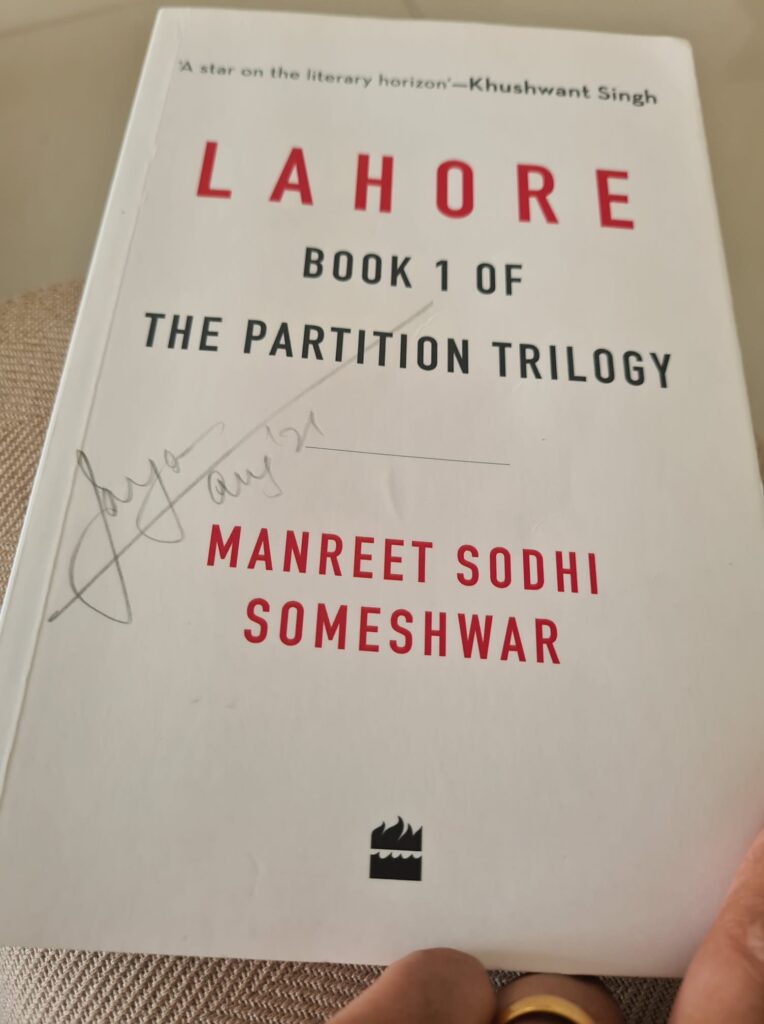

Manreet Sodhi Someshwar’s “Lahore”, part of the Partition Trilogy

…If religion was the basis of nationality, why there would be multiple nations in India. These nations exist in most villages, in varying proportions, with no boundaries. A Bengali Hindu and a Bengali Muslim live together, speak the same language, share the same customs. In Panjab, it is not uncommon in Hindu homes for the eldest son to be brought up a Sikh. Would that therefore mean two nations in one home? p.159

The first volume of “The Partition Trilogy” by Manreet Sodhi Someshwar , entitled Lahore is to be released very soon. When it is available in the market, buy it. Read it. It is excellent.

The publicity blurb states the following:

Set in the months leading up to and following India obtaining freedom in 1947, this trilogy is an exploration of events, exigencies and decisions that led to the independence of India, its concomitant partition, and the accession of princely states alongside. A literary political thriller that captures the frenzy of the time, the series is set in Delhi, Lahore, Hyderabad and Kashmir. Covering a vast canvas, Jawaharlal Nehru, Vallabhai Patel and Lord Mountbatten [ the text rather disparagingly refers to him as “Dickie” instead of “Lord”] share space in the trilogy with the ordinary people from the cities that were affected by the partition and the reorganization of the states.

Lahore is a very well-told story, delineating step-by-step the events that led to the subcontinent’s independence from its British colonial rulers and the heavy cost in terms of human lives. The story also focusses on the irrational hatred that consumed people. The author attempts a fine balance between the political events that were taking place at a rapid pace, sometimes leaving the politicians and administrators bewildered at the speed at which it was all happening, with that of the events engulfing common people. She offers insights into the macro- and micro- levels of decisions that needed to be taken by the British, and incoming Indian and Pakistani governments. The story moves extremely fast, aping the historical events. Lahore seems to based on extensive research involving historical documents, accounts, testimonies, more contemporary analysis that has been unearthed of the events that took place nearly seventy-five years ago. It is perceptible in the tenor of writing. It seeps through in the descriptions of the real and imagined characters — the state-level decisions that were being taken to manage the handing over of governance by the British to the Indians/Pakistanis, albeit the narrative focusses more on the Indian side; the brutal hacking of people on the streets simply because they were of the opposite community (“Communal rioting was spreading,as if by chain reaction”); the unreasonable acts of violence in neighbourhoods towards the “other” such as the fictionalised account of the Muslim fruit seller being shunted out of a predominantly Hindu colony ( eerily echoing present day India where a few days ago a similar act occurred towards a Muslim bangle seller in Indore); or the vicious assault, kidnapping and raping of women where often they were left to their fate ( “Nobody moved in pursuit, nobody seemed to have noticed her disappearance— or nobody had the energy left to care.”).

There is much, much more to absorb. It requires a keen historian’s eye to verify if the facts portrayed in this novel are as close to the truth as possible. In terms of the broader arc, the depiction of the events is close to what is evident in history books and the many oral testimonies that came tumbling out in the older generations as they recalled 1947 while witnessing the communal riots that had broken out in Delhi in 1984. The chilling parallels between the two were unmistakable. For instance, my grandfather, who was the last ICS officer, suddenly began to remember the 1947 horrors that he saw as a young officer. So much of what Manreet Sodhi Someshwar documents of the officers making lists of divvying up office furniture, watching people being slaughtered in the streets, or houses being burnt to the ground with families inside it are much of what my grandfather has recorded in his oral testimony at the Teen Murti Library. Apparently it is the longest oral testimony (4vols) ever recorded. It is also very familiar to those of us who have seen these riots. It is as if we as a nation cannot get rid of these violent memories and have made violence part and parcel of our lives. Today, with social media, recordings of such incidents spread like wildfire, igniting even more in other regions. It is incumbent upon us as responsible citizens of a democracy to remember the horrendous events of the past and learn to move on, rather than nurse communal hatred and replicate pogroms.

More than forty percent of the 1.4 billion Indian population was born after 1991, many of whom are unfamiliar with modern Indian history. But it can be accessed through various ways. By reading historical fiction such as Lahore in conjunction with history books such as Bipan Chandra’s History of Modern India and of course watching the classic film by Richard Attenborough, Gandhi, available in English and Hindi.

Lahore is truly magnificent. Although it is inexplicable why the book title is Lahore when the chapters spell it as “Laur”. It should be submitted for historical fiction literary prizes such as “Walter Scott Historical Fiction Prize” that is open to books published in the previous year in the Commonwealth. It would also be interesting to see a conversation between British writer Jamila Gavin who wrote the “Surya Trilogy” and Manreet Sodhi Someshwar as they both grapple with the events of 1947. Ideally Salman Rushdie should be invited to participate too given how his recent collection of essays dwells upon many of the themes that the other two writers tackle. Having said that there are many more writers who can be invited but this trio in conversation would make for a phenomenal conversation.

Buy it once it is available.

28 August 2021

PS I had posted this review on Facebook. Later Manreet Sodhi Someshwar shared it as her Facebook story. Here is a screenshot of it.