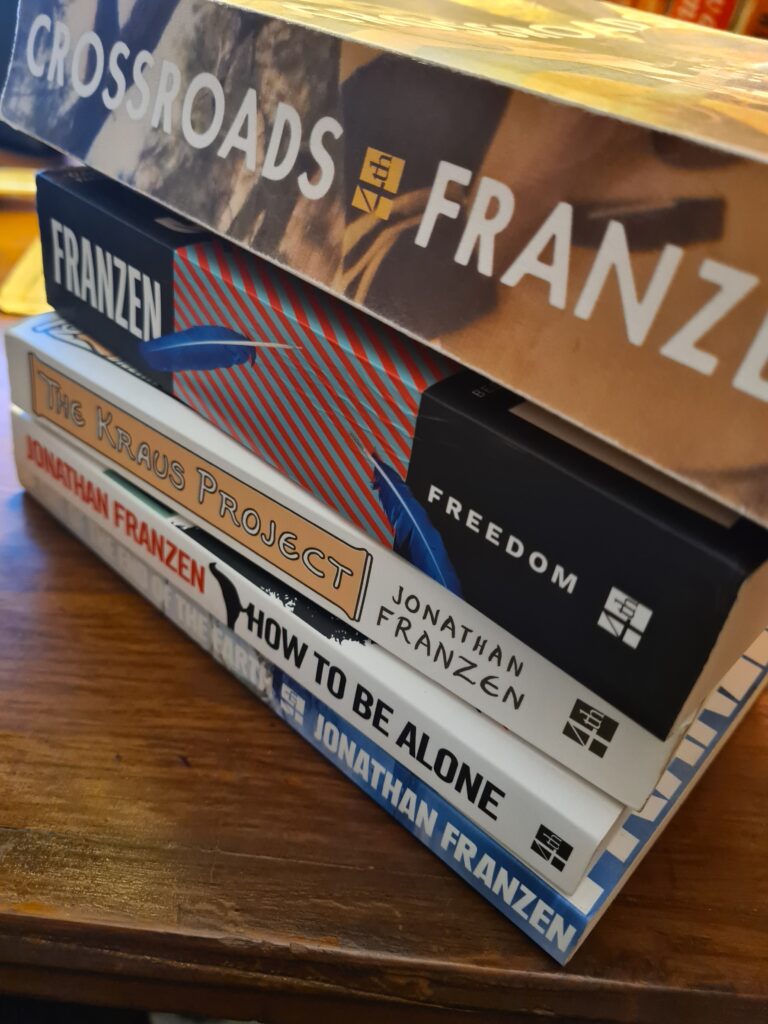

Jonathan Franzen “Crossroads”

I have liked Jonathan Franzen’s writings ever since I began reading his essays in the National Geographic and some other random places. Also, my admiration for him rose immensely once I discovered he had mentored a writer like Nell Zink. I have never understood why he was detested since he does not seem to brook fools. This new novel of his – Crossroads ( HarperCollins India)– is very good simply because it is not pretentious. His historical details like in the off-the-cuff references to music, life, clothes, etc. He also makes it clear in the speech formulations, sometimes in the slang used. I have not marked any passages in the book but when I was reading it, I thought to myself, oh this is so outdated but fits with the age. The whole point of the novel seems to be to focus on this middle-class white Christian family, a pastor’s family, the Hilderbrandts. As Marion constantly reminds herself and everyone that she is a Pastor’s wife, so many of her skills such as remembering useless details about individuals is her strength, a quality that marks a pastor’s family as it is expected of you. Franzen chooses to share exactly what he wishes to. The NYRB review questions the historical fiction aspect of the novel. The examples the reviewer takes out to highlight the lack of historicity are exactly what caught my eye as clever acts by Franzen. The reviewer misses out completely all the references to music, the slow intermingling of the white and black congregations, the silent pacts that the white and black pastors have, understanding how their flock has to be managed, the Navajo community etc. While reading Crossroads, I kept thinking about The Cross and the Switchblade.

It requires extraordinary talent required to create the back stories of individuals. Marion may be the flimsiest and vaguest woman but hers is amongst the strongest portrayals in the book. It is brilliant. Her descent into a nervous breakdown is stupendous. The novel is so much about the white middle class crisis, a family saga, a Christian family, the huge hold of the church upon its congregation and the way life revolves around the church – the idea of community. Recent reviews have dismissed the party at the main pastor’s house in one line but it is a crucial part of the story. The guests were from different denominations and religions, there was even a rabbi, and the smattering of conversations one hears, is a pretty good analysis of faith and the questions it raises – the importance of religion in modern society. The manic-depressive junkie son, Perry Hildebrandt, brings this party to a halt with his statements about what it means to be good or not, especially in the eyes of these men, leaders of their flock.

Franzen is playing on the title of the Key to all Mythologies, a reference to Casaubon’s unfinished book in Middlemarch, and mocking modern readers for their high falutin, obnoxious takes on being woke about various issues esp. black and minority cultures. He is just sharing as is. Franzen is achieving two things:

- He is calling out all this pretentiousness of liberals today of genuflecting towards minorities and giving them their dues. With this story he is trying to say, look you choose to see what you chose but whites did culturally appropriate much of the black culture in their lives and called it their own, such as Cream’s Crossroads lifting Robert Johnson’s song, but then Crossroads is also the name of the Youth Fellowship in the church – confusion galore! So Franzen is really showing his exasperation.

- In the pandemic, literature about the pandemic and other anxieties are being much lauded, but by displaying the ordinariness of family and church life, he is making people rethink the value of family, community and simple pleasures. Although there is enough drama in each individual’s life to merit a book by itself.

Crossroads is more than just an American novel. It is an incredible master class in the art of writing good literary fiction. It is also a way of sharing memories, histories and incredibly delving into the microcosm of a family. Usually, family saga novels tend to focus on a single character and then all the other relatives pale into insignificance. Or family sagas take generations to play out, with the novelist devoting many pages to each generation. In this case, he has written over 600 pages to cover a very short period of time, giving everyone due weightage — and yet not. The varying lengths of each backstory for every individual is a testament to Franzen’s craftsmanship. He is not out to prove that he can do great literary writing. He is giving every character as much is their due. He is so right in saying that he puts down what he sees. Heavens this man is quite the observer and listener. Much of the time, I feel like screaming and saying, “Yes, yes, he got this so well!” The whole idea of creating a mythical town that is really in the suburbs of Chicago, but is a conservative Christian community is done so well. Franzen too spent time in a Church Youth Fellowship. Anyone who is even remotely familiar with church communities and their groups, may realise that these gatherings can get so claustrophobic and stifling and develop their own inner dynamics that then spill out in other parts of life. Franzen gets this really well — the power of the church, the idea of the spiritual and how much of it is really driven by mortal, base and materialistic desires. Also, how much of the outer world preoccupations do not make any dent on this small community. They seem to sail on as before till the cracks begin to develop. The outside world makes its presence felt only because Franzen makes it happen as an external force that is affecting the lives of the characters. Beginning with Clem Hildebrandt, the eldest son of the pastor. A privileged white male who has the option of pursuing University but chooses to give it up to join the Vietnam war. His sister who falls in love with a musician, Tanner, who too nurses an ambition to cut a commercially successful record, but is aware that it can only happen if he leaves this small town. Or even the pastor, the shepherd of the flock, who does all this good work but is bored of his wife and is eyeing the young widow, Frances. It is so complicated. So ordinary. So mundane. But Franzen does not make it so. And so much focus on Russ, the priest, and mocking him but also justifying the choices he makes is an interesting take on a man who is supposed to be a shepherd, a leader but is so out of touch with the youngsters. The idea of a community is very critical to Franzen. He mentioned it in one of his recent essays as an aside. He is keen to give to his community and does his best for it too. So, it is an ideal central to his thinking in this book too.

With the title Crossroads Franzen gives the reader multiple interpretations for the word. Beginning with the Cream album of the same name, that was actually a cover version of the blues musician Robert Johnson’s original composition to many of the characters in the book being at the moral crossroads of a situation to being at the crossroads of life. So many layers to the word. It is utterly fascinating. The crisis that Franzen depicts in the lives of these characters is no different to many other ordinary lives. It is no wonder that Crossroads has taken many people by surprise and is getting fantastic reviews everywhere because there is no pretension; it is up front and Franzen says it like he means.

Links to some reviews:

Guardian ; Slate ; The Bookseller ; https://www.avclub.com/jonathan-franzen-sticks-with-what-works-and-loses-what-1847751729 ; BBC ; https://www.vulture.com/article/interview-jonathan-franzen-crossroads.html?utm_source=tw

I look forward to Parts 2 & 3.

4 October 2021