“Reconciliation: Karwan e Mohabbat’s Journey of Solidarity through a Wounded India”

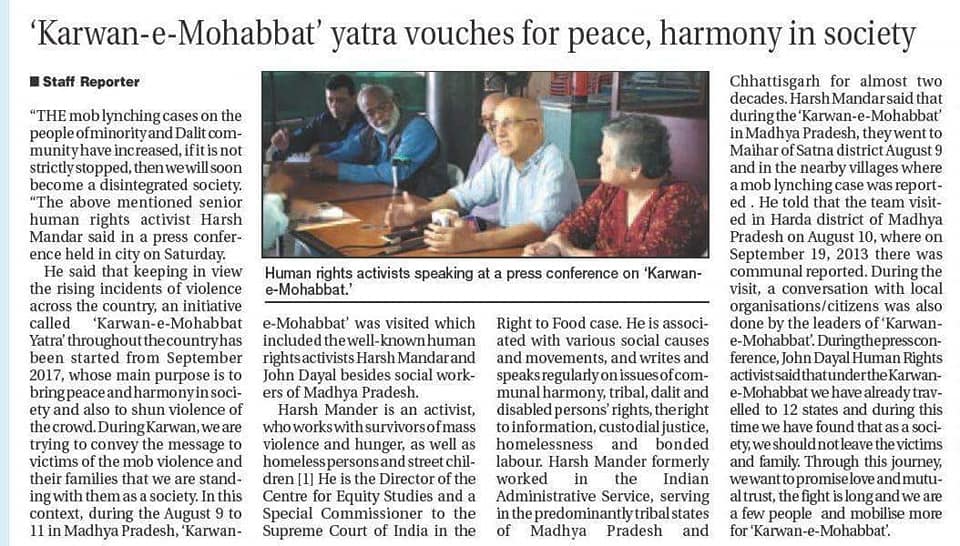

On 4 September 2017, a group of volunteers led by Harsh Mander travelled across eight states of India on a journey of shared suffering, atonement and love in the Karwan e Mohabbat, or Caravan of Love. It was a call to conscience, an attempt to seek out and support families whose loved ones had become victims of hate attacks in various parts of the country. Along the way they met families of victims who had been lynched as well as some of those who had managed to survive the lynching. The bus travelled through the states, meeting with people and listening to their testimonies. It is a searingly painful account of the terror inflicted in civil society that has seen a horrific escalation in recent months.

The book is clearly divided into sections consisting of an account of the journey based upon the daily updates Harsh Mander wrote every night. It is followed by a collection of essays by people who travelled in the bus. There is also a selection of testimonies recorded by journalist Natasha Badhwar of her fellow passengers. Many of whom joined only for a few days but were shattered by what they saw and heard.

Reconciliation is powerful and it is certainly not easy to read knowing full well that this is the violence we live with every day. The seemingly normalcy of activity we may witness in our daily lives is just a mirage for the visceral hatred and hostility that exists for “others”. It is a witnessing of the breakdown of the secular fabric of India and a polarisation along communal lines that is ( for want of a better word) depressing. Given below are a few lines from the introduction written by human rights activist Harsh Mander followed by an extract by Prabhir Vishnu Poruthiyil. Prabhir who was on the bus is an assistant professor at the Indian Institute of Management Tiruchirapalli (IIMT), India. The extract is being used with the permission of the publishers.

Everywhere, the Karwan found minorities living in endemic and lingering fear, and with hate and state violence, resigned to these as normalised elements of everyday living.

…..

Our consistent finding was that families hit by hate violence were bereft of protection and justice from the state. In the case of almost all the fifty-odd families we met during our travel through eight states, the police had registered criminal charges gainst the victims, treating teh accused with kid gloves, leaving their bail applications unopposed, or erasing their crimes altogether.

. . .

More worrying by far was our finding that the police had increasingly taken on the work of lynch mobs. There were tens of instances of the police executing Muslim men, alleging that they were cattle smugglers or dangerous criminals, often claiming that they had fired at the police. Unlike mob lynching, murderous extrajudicial action has barely registered on the national conscience. It is as though marjoritarian public opinion first outsourced its hate violence to lynch mobs, and lynch mobs in BJP-ruled states like UP, Haryana and Rajasthan are now outsourcing it onwards to the police. ( Introduction, p.x-xi)

Prabhir Vishnu Poruthiyil is an assistant professor at theIndian Institute of Management Tiruchirapalli (IIMT), India. He teachesbusiness ethics and his research is focused on the influence of business oninequalities and the rise of religious fundamentalism.

Like many others, I grew up with the usual doseof religiosity and nationalism. But I was also enrolled in a Hindu school (Chinmaya Vidyalaya) that injected an additional dose of Hindu supremacy. Therewas a short phase in my life (jobless, in my mid-twenties) when I went aboutexploring and trying to understand and justify Hinduism. I am the kind of person who tends to immerse himself fully to understand and make sense of theworld. My exploration brought me in close contact with gurus in various ashrams and bhajan groups. I learned Vedic chanting, studied Hindu theology, and even dallied with the idea of becoming a monk. I interacted with groups and individuals committed to Hindutva and attempted to see the world from their perspective (many remain my friends). I could not put my finger on it then, butI was deeply uncomfortable with what I later realised was unadulterated hatred and a stifling resistance to questioning and reason.

Around this time, in 2004, I was admitted into a masters and then a PhD programme in the Netherlands. Lectures by my teachers and exposure to the lives of classmates and refugees with personal experiences of life in theocratic regimes accelerated my disgust with religious nationalism of all kinds. Exposure to liberal political philosophy and to Dutch society made me appreciate the benefits of living in a place run on democratic and rational principles. As my education both in and outside the classroom progressed, my fascination with extreme perspectives rapidly diminished andturned into concern and disgust. It was, however, a visit to Auschwitz in 2012 that made me realise how easy it was for a society to be sufficiently intoxicated by supremacist world views to justify the annihilation of those deemed inferior. That a human tragedy on this scale had happened in the same society that had made incredible contributions to art, philosophy and music was unthinkable.

Over time, I have lost what remains of my beliefin the supernatural and purged myself of superstitions. I would now call myself a rationalist or secular humanist. Ibelieve that the irrationality promoted by religion is a barrier to progress and that religion is unnecessary for morality, and not a guarantee of it.

When I returned to India in 2013 to join the IIM, I did not expect religious nationalism to influence my research in, andteaching of, business ethics. My focus was on inequality. With the BJP’s victory in 2014 and the support of the corporate sector for the party, it became impossible to disentangle business ethics from religious nationalism. Istarted research on a paper on how religious nationalism emerges and whatbusiness schools could do to resist its advance.

When the lynchings began, more than thepsychology of the vigilantes and their victims, my sociological interest waspiqued by the nonchalance and even the endorsement of cow-vigilantism by many people I cared for, particularly among my family, friends, colleagues andstudents. Their unwillingness to recognise bigotry for what it was and rejectpolitical leaders who create an atmosphere of hate resembled the attitudes prevalent in Germany during the Nazi era. It disturbed me deeply to see sectarianism slowly taking hold of persons I loved. I started to worry that the possibility of concentration camps being built in India was no longer a gross exaggeration.

In the meantime, I had initiated a conversation with Harsh Mander. I wished to invite him to give a lecture at the IIM inTrichy. When the Karwan e Mohabbat was announced, I felt it was important to take part. I wanted to see for myself and talk about it to my friends and family and to students in my classes. The experience of looking into the eyesof persons who had lost loved ones was emotionally tough. After each meeting, my mind was constantly wondering how human beings could allow such tragedies to happen. A quote by Gandhi kept ricocheting in my brain: ‘It has always been a mystery to me how men can feel themselves honoured by the humiliation of their fellow beings.’

Looking back now, the memories and emotions of my visits to Auschwitz and of the victims of Hindutva are difficult to distinguish. The same helplessness, resentment and fear captured in the countless pictures of Jews subjected to the Holocaust seem to be reflected inthe eyes of the victims of cow-vigilantism. In contemporary India, I worry it may be unnecessary to build a standalone Auschwitz to implement a sectarian agenda. Terror has been decentralised and imposed through a variety of spaces. The entire country now risks being transformed into one large concentration camp.

How do we push back? Being a committed rationalist, my first instinct is to train citizens to use their reasoning and the language of liberalism and human rights to push back against bigotry andreligious nationalism. But the inroads made by Hindu nationalism into thepsyche can make it difficult for liberal vocabularies to reverse. The languageof ‘human rights’ and ‘freedom of speech’ can be branded as alien and hence ridiculed and dismissed. Furthermore, there are studies that show how groups tend to cling more firmly to their beliefs when threatened by outsiders.

Observant Hindus can be convinced more easily that sectarian hate and bigotry goes against the grain of Hinduism. The definition of Hinduism could be expanded to encompass empathy and compassion.This strategy would require formulating something like the liberation theologythat emerged in Latin America to challenge the interlocking interests of thebusiness elite and the top echelons of the Church that perpetuated inequality.

Excerpted with permission from RECONCILIATION:Karwan e Mohabbat’s Journey of Solidarity through a Wounded India, Harsh Mander, Natasha Badhwar and John Dayal, Context, Westland 2018.

The pictures in the gallery are from Karwan e Mohabbat‘s Facebook page.

19 December 2018