Book Post 37: 20 – 25 May 2019

Book Post 37 includes some of the titles received in the past few weeks.

27 May 2019

( My review of Zadie Smith’s new novel, Swing Time, has been published in Scroll today. Here is the original url: http://scroll.in/article/824448/a-new-zadie-smith-a-new-set-of-difficulties-in-reading-a-new-pleasure . I am also c&p the text below.)

The baby was surrounded by love. It’s a question of what love gives you the right to do.

Zadie Smith’s latest novel Swing Time is about two young girls, Tracey and a nameless narrator, who live in council housing of 1980s London. These young girls are of mixed parentage who have been born different shades of brown as a result. They are not exactly social misfits but are not entirely accepted by their classmates as is apparent when they get invited to Lily Bingham’s tenth birthday party. The two girls are completely out of their depth as are their mothers who are clueless on how to guide the youngsters.

Was it the kind of thing where you dropped your kid off? Or was she, as the mum, expected to come into the house? The invitation said a trip to the cinema – but who’d pay for this ticket? The guest or the house? Did you have to take a gift? What kind of gift were we getting? …It was as if the party was taking in some bewildering foreign land, rather than a three-minute walk away, in a house on the other side of the park.

Swing Time is narrated in first person bringing to the story an intimacy, a close involvement between the reader and narrator, which would otherwise be missing if it was narrated in third person. This intimate relationship between narrator and reader helps particularly if Swing Time is read as a bildungsroman. The firm childhood friendship of the narrator and Tracey seems to peter away in adulthood. Yet the narrator’s flashbacks focus inevitably on the time she spent growing up in Thatcherite London with Tracey, to a large extent informing her adult life — emphasising the quality of “shared history“, an important aspect of friendships to Zadie Smith. (Friendships are a characteristic trait of her fiction.) Swing Time zips particularly once the billionaire singer, Aimee, hires the narrator as one of her personal assistants. The storytelling pace matches the heady life of the superstar who flits through her own life juggling various roles such as of being a mother, her performances, recording music, and charitable “good work” in Africa by sponsoring schools.

Amongst the early book reviews of the novel there is a common refrain that the story fails to match the potential of a writer like Zadie Smith, deteriorating into contrived, formulaic and predictable storytelling. Trying to read Swing Time in the traditional manner is an excruciating task. The sentences are structured in such an unpredictable manner – sometimes running on in a Jamesian style for pages on end in an uninterrupted paragraph. The swift shifts in tone from meditative introspection to commentary and sharp judgement by the narrator can be disconcerting. But if you shift the classical expectations of what the book should deliver to that of a novel written by an artist AND a mother — it suddenly transforms. It is more about an artist being a successful professional while managing her time as a mother too. Here is the narrator talking about her mother who puts herself through college while her daughter is still in school, later the mother becomes a prominent politician.

Oh, it’s very nice and rational and respectable to say that a woman has every right to life, to her ambitions, to her needs, and so on – it’s what I’ve always demanded myself –but as a child, no, the truth is it’s a war of attrition, rationality doesn’t come into it, not one bit, all you want from your mother is that she once and for all admit that she is your mother and only your mother, and that her battle with the rest of life is over. She has to lay down her arms and come to you. And if she doesn’t do it, then it’s really a war, and it was a war between my mother and me. Only as an adult did I come to truly admire her – especially in the last, painful years of her life – for all that she had done to claw some space in this world for herself. When I was young her refusal to submit to me confused and wounded me, especially as I felt none of the usual reasons of refusal applied. I was her only child and she had no job – not back then – and she hardly spoke to the rest of the family. As far as I was concerned, she had nothing but time. Yet still I couldn’t get her complete submission! My earliest sense of her was of a woman plotting an escape, from me, from the very role of motherhood.

There are portraits, references and pithy observations on mothering or the relationship between mothers and children. There are the mothers of the two girls – Tracey and narrator, the grandmothers in the family compound of African schoolteacher Hawa, the mothers of the African school children, Aimee and her children and Tracey and her brood. In some senses this novel too with its overdone cultural references especially of the recent past also becomes a record of events for Zadie Smith’s children’s generation.

In June 2013 Zadie Smith along with Jane Smiley objected to the suggestion made by journalist and author Lauren Sandler that they should restrict the size of their families if they want to avoid limiting their careers. Writing in the Guardian, Zadie Smith said, “”I have two children. Dickens had 10 – I think Tolstoy did, too. Did anyone for one moment worry that those men were becoming too fatherish to be writeresque? Does the fact that Heidi Julavits, Nikita Lalwani, Nicole Krauss, Jhumpa Lahiri, Vendela Vida, Curtis Sittenfeld, Marilynne Robinson, Toni Morrison and so on and so forth (I could really go on all day with that list) have multiple children make them lesser writers?” said Smith. “Are four children a problem for the writer Michael Chabon – or just for his wife, the writer Ayelet Waldman?” Smith added that the real threat “to all women’s freedom is the issue of time, which is the same problem whether you are a writer, factory worker or nurse”. A sentiment echoed in Swing Time when she writes: “The fundamental skill of all mothers [is] the management of time”.

In the end the narrator learns to appreciate Tracey’s balancing act as a professional and a mother — like a dance.

She was right above me, on her balcony, in a dressing gown and slippers, her hands in the air, turning, turning, her children around her, everybody dancing.

Swing Time is a mesmerising if at times a challenging read. It is the portrait of an artist AND a mother.

Zadie Smith Swing Time Hamish Hamilton, an imprint of Penguin Books, Penguin Random House, London, 2016. Pb. Pp.454 Rs. 599

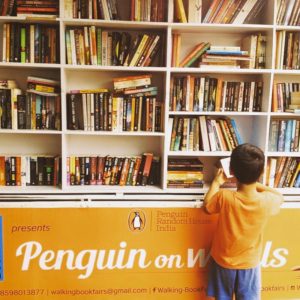

( I wrote an article for the amazing literary website Bookwitty.com on “Penguin on Wheels”. An initiative of Walking BookFairs and Penguin Books India. It was published on 28 June 2016. Here is the original url: https://www.bookwitty.com/text/penguin-on-wheels-walking-bookfairs-and-penguin-b/57725752acd0d076db037bf7 . I am also c&p the text below. )

( I wrote an article for the amazing literary website Bookwitty.com on “Penguin on Wheels”. An initiative of Walking BookFairs and Penguin Books India. It was published on 28 June 2016. Here is the original url: https://www.bookwitty.com/text/penguin-on-wheels-walking-bookfairs-and-penguin-b/57725752acd0d076db037bf7 . I am also c&p the text below. )

Literature does not occur in a vacuum. It cannot be a monologue. It has to be a conversation, and new people, new readers, need to be brought into the conversation too.”

-Neil Gaiman, Introduction, The View from the Cheap Seats ( 2016)

On the 16th of May 2016, Penguin Random House India circulated a press release about Penguin Books India’s one-year collaboration with Walking BookFairs (WBF) to launch “Penguin on Wheels”, a bookmobile that will travel through the eastern Indian state of Odisha promoting reading and writing.

This is not the first time Walking BookFairs has collaborated with a publishing house to promote reading. Their earlier “Read More, India” campaign saw Walking BookFairs supported by HarperCollins India, Pan MacMillan India, and Parragon Books India. Apart from these three publishers, WBF stocked books from various other publishers, including Tara Books, Speaking Tiger Books, Penguin, Duckbill, Karadi Tales, and Scholastic. “We got books delivered by our publishers on the road wherever we were displaying books.”

The concept of bookmobiles is not unusual in India, for some decades the state-funded publishing firm, National Book Trust, has maintained its own book vans. Yet it is the duo of Satabdi Mishra and Akshaya Rautaray that has captured the public imagination.

Walking BookFairs was established two years ago while Satabdi Mishra was on a break from her job and Akshaya  Rautaray quit his publishing job to set up an independent “simple bookstore” in Bhubaneshwar. The shop, which they prefer to think of as a “book shack”, runs on solar power. It is a simple space with the bare necessities and a garden. They allow readers to browse through the bookshelves, offering a 20-30% discount on every purchase throughout the year.

Rautaray quit his publishing job to set up an independent “simple bookstore” in Bhubaneshwar. The shop, which they prefer to think of as a “book shack”, runs on solar power. It is a simple space with the bare necessities and a garden. They allow readers to browse through the bookshelves, offering a 20-30% discount on every purchase throughout the year.

WBF also doubles as a free library. They introduced the bookmobile in 2014, as part of an outreach programme that would see them travelling to promote reading in the state. Speaking to me by email, Satabdi said,

“There are no bookshops or libraries in many parts of India. There are thousands of people who have no access to books. We started WBF in 2014 because we wanted to take books to more people everywhere. We have been travelling inside our home state Odisha for the last two years with books. We found that most people do not consider reading books beyond textbooks important in India. We wanted people to understand that reading story books is more important than reading textbooks. We wanted to reach out to more people with books. We also wanted to inspire and encourage more people across the country to read books and come together to open more community libraries and bookshops.”

India is well known for stressing the importance of reading for academic purposes rather than reading for pleasure. In a country of 1.3 billion people, where 40% are below the age of 25 years old, and the publishing industry is estimated to be of $2.2 billion, there is potential for growth. Indeed,there has been healthy growth across genres, quite unlike most book markets in the world.

The WBF team has been keen to promote reading since it is an empowering activity. They began in the tribal district of Koraput, Odisha, where they carried books in backpacks and walked around villages. They displayed books in public spaces like bus stops and railways stations or spreading them out on pavements or under trees, whatever was convenient and accessible. “That works because people in smaller towns feel intimidated by big shops,” they say.

Apart from public book displays, they also visit schools, colleges, offices, educational institutions, and residential neighbourhoods. They soon discovered that children and adults were not familiar with books. Bookstores too seem only to be found in urban and semi-urban areas and are lacking in rural areas, but once easy access to books is created there is a demand. As Neil Gaiman says in the essay “Four Bookshops”, these bookshops “made me who I am”, but the travelling bookshop that came to his day boarding school was “the best, the most wonderful, the most magical because it was the most insubstantial”. (The View from the Cheap Seats)

Speaking again via email, Satabdi says that they’ve found, “Children’s books are always the most sought after. We have many interesting children’s storybooks and picture books with us. We found that in many places, not just children but also adults and young people enthusiastically pick up children’s books, browse through and read them. Beyond a couple of urban centres in India, big cities, there are no bookshops. Most bookshops that one comes across are shops selling textbooks, guide books or essay books. Many people were actually looking at real books for the first time at WBF.”

In India the year-on-year growth rate for children’s literature is estimated to be 100%. Satabdi Mishra and Akshaya Rautaray stock 90% fiction. Rautaray says, “We believe in stories. I think, if you need to understand the world around you, if you need to understand science and history and sociology, you need to understand stories. I believe in a good book, a good story.”

The categories include literary fiction, classics, non-fiction, biographies, books on poetry, cinema, politics, history, economics, art visual imagery, young adult, picture books, children’s books, and regional literature from Odia and Hindi. The emphasis is on diversity, but they do not necessarily stock bestsellers or popular books like romance, textbooks, or academic books. That said, the Penguin on Wheels programme will dovetail beautifully with, “Read with Ravinder” another of the publisher’s reading promotion campaigns, spearheaded by successful commercial fiction author Ravinder Singh.

In December 2015, Satabdi and Akshay launched their “Read More, India” campaign (#ReadMoreIndia), which saw them take their custom-built book van, loaded with more than 4000 books across India. They covered 10,000kms, 20 states, in three months (from 15th Dec 2015 to 8th March 2016).

Over the course of the journey, they sold forty books a day, met thousands of people, and had a number of interesting experiences. One anecdote that gives an insight into the passion and trust that the young couple displays is of that of an elderly gentleman in Besant Road Beach road, Chennai. The older man was out for his daily jog and stopped to look at the books. He wanted to buy some books, but had left his wallet behind.

“We asked him to take the books and pay us later via cheque or bank transfer. He seemed surprised that we were letting him take the books without paying. He took the books and sent the money later with his driver. We want people to read more books. And if people cannot buy books, we want them to read books for free for as long as they want. People pay us in cash, in kind, sometimes they take books pay later, pay through credit/debit cards.”

The Penguin on Wheels campaign was launched because Penguin Books India had been following WBF’s activities and reached out to them. Earlier, they had collaborated for an author event in Odisha, but this new move is a focussed effort that will see the bookmobile travel within Odisha.

The books are curated by Akshay as Penguin Books India said graciously that “they [WBF] know best what their readers like more”. It will consist of approximately 1000 titles from the Penguin Random House stable. The collection will have books by celebrated authors, including Jhumpa Lahiri, John Green, Orhan Pamuk, Amitav Ghosh, Devdutt Pattanaik, Salman Rushdie, Ravinder Singh, Twinkle Khanna, Hussain Zaidi, Khushwant Singh, Roald Dahl, Ruskin Bond, and Emraan Hashmi.

Contests and author interactions will also be organised with the support or Penguin Random House. It will start with Ravinder Singh’s visit to Bhubaneshwar for the promotion of his newly launched book, Love that Feels Right. Satabdi Mishra adds, “We are happy to partner with PRH through the WBF ‘Penguin on Wheels’ that will spread the joy of reading around.”

Jaya Bhattacharji Rose

28 June 2016

According to the vision statement, the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature celebrates the rich and varied world of literature of the South Asian region. Authors could belong to this region through birth or be of any ethnicity but the writing should pertain to the South Asian region in terms of content and theme. The prize brings South Asian writing to a new global audience through a celebration of the achievements of South Asian writers, and aims to raise awareness of South Asian culture around the world. This year the award will be announced on 22 January 2015, at the Jaipur Literature Festival, Diggi Palace, Jaipur.

According to the vision statement, the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature celebrates the rich and varied world of literature of the South Asian region. Authors could belong to this region through birth or be of any ethnicity but the writing should pertain to the South Asian region in terms of content and theme. The prize brings South Asian writing to a new global audience through a celebration of the achievements of South Asian writers, and aims to raise awareness of South Asian culture around the world. This year the award will be announced on 22 January 2015, at the Jaipur Literature Festival, Diggi Palace, Jaipur.

The DSC Prize for South Asian Shortlist 2015 consists of:

1. Bilal Tanweer: The Scatter Here is Too Great (Vintage Books/Random House, India)

2 Jhumpa Lahiri: The Lowland (Vintage Books/Random House, India)

3. Kamila Shamsie: A God in Every Stone (Bloomsbury, India)

4. Romesh Gunesekera: Noontide Toll (Hamish Hamilton/Penguin, India)

5. Shamsur Rahman Faruqi: The Mirror of Beauty (Penguin Books, India)

( http://dscprize.com/global/updates/five-novels-make-shortlist-dsc-prize-2015.html )

The jury consists of Keki Daruwala (Chairperson), John Freeman, Maithree Wickramasinghe, Michael Worton and Razi Ahmed.

All the novels shortlisted for the award are unique. They put the spotlight on South Asian writing talent. From debut novelist ( Bilal Tanweer) to seasoned writers ( Jhumpa Lahiri, Romesh Gunesekera and Kamila Shamsie) and one in translation – Shamsur Rahman Faruqui, the shortlist is a good representation of the spectrum of contemporary South Asian literature in English. Three of the five novelists– Jhumpa Lahiri, Romesh Gunesekera and Kamila Shamsie–reside abroad, representing South Asian diaspora yet infusing their stories with a “foreign perspective”, a fascinating aspect of this shortlist. It probably hails the arrival of South Asian fiction on an international literary map. The three novels — The Lowland, Noontide Toll and A God in Every Stone are firmly set in South Asia but with the style and sophistication evident in international fiction, i.e. detailing a story in a very specific region and time, culturally distinct, yet making it familiar to the contemporary reader by dwelling upon subjects that are of immediate socio-political concern. For instance, The Lowland is ostensibly about the Naxalite movement in West Bengal, India and the displacement it causes in families; A God in Every Stone is about an archaeological dig in Peshawar in the period around World War I and Noontide Toll is about the violent civil unrest between the Sinhala and Tamils in Sri Lanka. Yet all three novels are infused with the writers’ preoccupation with war, the immediate impact it has on a society and the transformation it brings about over time. The literary techniques they use to discuss the ideas that dominate such conversations — a straightforward novel (The Lowland), a bunch of interlinked short stories narrated by a driver ( who is at ease in the Tamil and Sinhala quarters, although his identity is never revealed) and the yoking of historical fiction with creation of a myth as evident in Kamila Shamsie’s A God in Every Stone. All three novelists wear their research lightly, yet these novels fall into the category of eminently readable fiction, where every time the story is read something new is discovered.

Bilal Tanweer who won the Shakti Bhatt First Book Prize 2014 for his wonderful novel, The Scatter Here is Too Great. Set in Karachi, it is about the violence faced on a daily basis. (Obviously there is much more to the story too!) Whereas Shamsur Rahman Faruqi’s novel The Mirror of Beauty, translated by him from Urdu into English is primarily about Begum Wazir Khanam with many other scrumptious details about lifestyles, craftspeople, and different parts of India. It is written in a slow, meandering style of old-fashioned historical fiction. The writer has tried to translocate the Urdu style of writing into the English version and he even “transcreated” the story for his English readers—all fascinating experiments in literary technique, so worth being mentioned on a prestigious literary prize shortlist.

Of all the five novels shortlisted for this award, my bet is on Kamila Shamsie winning the prize. Her novel has set the story in Peshawar in the early twentieth century. The preoccupations of the story are also those of present day AfPak, the commemoration of World War I, but also with the status of Muslims, the idea of war, with accurate historical details such as the presence of Indian soldiers in the Brighton hospital, the non-violent struggle for freedom in Peshawar and the massacre at Qissa Khwani Bazaar. But the true coup de grace is the original creation of Myth of Scylax — to be original in creating a myth, but placing it so effectively in the region to make it seem as if it is an age-old myth, passed on from generation to generation.

13 January 2015

Here are some links from the Jaipur Literature Festival 2013 and 2014 available on YouTube that I have enjoyed watching. Enjoy!

Here are some links from the Jaipur Literature Festival 2013 and 2014 available on YouTube that I have enjoyed watching. Enjoy!

17 June 2014

( My article on the Man Booker Prize 2013 has been published today in the Op Ed page of the Hindu, 19 Oct 2013. Here is the link: http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/the-long-and-winding-road-to-the-booker/article5248697.ece?homepage=true . The article is published below.)

On October 15, 2013, the Man Booker Prize was awarded to Eleanor Catton for The Luminaries — a thriller spread over 800 pages with a variety of voices recounting and recreating details. It was a win that surprised many. Set in 1866 in a small town on New Zealand’s South Island, the story begins when a traveller and gold prospector, Scotsman Walter Moody, interrupts a meeting of 12 men at Hokitika’s Crown Hotel. These men are immigrants but locals now who gather in secrecy to solve crimes. The novel is about the mystery surrounding the death of Crosbie Wells and the stories told by those 12 men. The narrative architecture is based on the 12 signs of the zodiac and the seven planets; each chapter is half the length of its predecessor, adding pace and tension. Of the books shortlisted — Jim Crace’s Harvest, Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Lowland, Ruth Ozeki’s A Tale for the Time Being, Colm Toibin’s The Testament of Mary, and Noviolet Bulawayo’s We Need New Names — it was widely assumed that the battle for the winning post would be between Jim Crace and Colm Toibin.

The Luminaries is in the tradition of a good, well-told, 19th century English novel. It has a leisurely pace with the story slowly being told, bit by bit. Eleanor Catton has trained at the best creative writing schools and is an alumna of the prestigious University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop. But this novel is an example of original thinking and excellent craftsmanship that are not easily taught.

The chair of judges, Robert Macfarlane, described the book as a “dazzling work, luminous, vast.” It is, he said, “a book you sometimes feel lost in, fearing it to be ‘a big baggy monster’, but it turns out to be as tightly structured as an orrery.” It is true that the 19th century novels were serialised (for example Charles Dickens and Anthony Trollope) and then put together as a book. Present day writers are taking advantage of virtual publishing to do something similar. The Kills by Richard House, long listed for the Man Booker Prize 2013, actually began life as four enhanced e-books that were then published as a single printed volume. But in the 21st century, to first publish in print such a thick book as The Luminaries takes extraordinary courage — a fact that did not go unnoticed even by Catton. In her acceptance speech she said, “… The Luminaries is and was from the very beginning, a publisher’s nightmare. […] I am extraordinarily fortunate to have found a home at these publishing houses and to […] have managed to strike an elegant balance between making art and making money.”

At 28, Eleanor Catton is the youngest winner of the Booker. (Before her the prize went to Ben Okri who won it when he was 32 for The Famished Road.) Catton was born in Canada and raised in Christchurch, New Zealand. The Booker is Britain’s most prestigious literary prize, awarded annually to a novelist from Britain, Ireland or a Commonwealth country. The winner receives £50,000, or about $80,000. The winner is selected by the judging panel on the day of the ceremony. In September 2013, it was announced that from next year the prize will be open to all those publishing in English, across the world, a move that has not necessarily been received well by many writers. Jonathan Taylor, chairman of the foundation, wrote at the time: “Paradoxically it has not […] allowed full participation to all those writing literary fiction in English. It is rather as if the Chinese were excluded from the Olympic Games.”

It is a fortunate coincidence that in 2013, three of the high-profile international awards for literature have been won by women — all for very distinct kinds of writing. Lydia Davis won the fifth Man Booker International Prize 2013 for her short stories (the length of her stories vary from two sentences to a maximum of two to three pages) and the Nobel Prize for Literature 2013 to Alice Munro, for her short stories and Eleanor Catton, Man Booker Prize 2013, for a novel that has been described as a “doorstopper.” For the world of publishing, these achievements sets the seal of approval on craftsmanship. It is probably recognition of geographical boundaries disappearing in digital space, conversations happening in real time and emphasis being placed on good content. It’s not the form but the craft that matters. Eleanor Catton’s Man Booker Prize win is a testament to the new world of publishing.

(Jaya Bhattacharji Rose is an international publishing consultant and columnist. E-mail:jayabhattacharjirose @gmail.com)

19 Oct 2013

The most ordinary details of his life which would have made no impression on a girl from Calcutta, were what made him distinctive to her.

The most ordinary details of his life which would have made no impression on a girl from Calcutta, were what made him distinctive to her.

( p.76)

Subhash and Udayan, brothers, a little over a year apart are academically very bright students who join Presidency College and Jadavpur respectively. Everyone, in the neighbourhood and their parents, are delighted. Subhash later goes to USA for his Ph.D. Udayan joins the Naxal movement. Hardly surprising given that this is Calcutta of the late 1960s. Lowland is about the brothers who were extremely close but their lives charted a course diametrically opposite to each other. Subhash has the predictable, straightforward, middle class life whereas Udayan a naxal is killed in a police encounter.

The Lowland was released with a tremendous amount of hype. The unveiling of the book cover ( at least in India) was done dramatically with press releases and social media chatter. The anticipation of reading a new novel by Jhumpa Lahiri was nerve-wracking. (Ever since her debut collection of short stories, Interpreter of Maladies, I have admired her writing.) Before the book was released on 8 Sept 2013, there were the usual number of articles, interviews, and profiles of her. The extract published in the New Yorker on 10 Jun 2013 was promising. (http://www.newyorker.com/fiction/features/2013/06/10/130610fi_fiction_lahiri) Her interview on 5 Sept 2013 in the New York Times stands out. ( http://www.nytimes.com/2013/09/08/books/review/jhumpa-lahiri-by-the-book.html?pagewanted=all ) In it she refuted all claims of writing “immigrant fiction”. Her reply:

I don’t know what to make of the term “immigrant fiction.” Writers have always tended to write about the worlds they come from. And it just so happens that many writers originate from different parts of the world than the ones they end up living in, either by choice or by necessity or by circumstance, and therefore, write about those experiences. If certain books are to be termed immigrant fiction, what do we call the rest? Native fiction? Puritan fiction? This distinction doesn’t agree with me. Given the history of the United States, all American fiction could be classified as immigrant fiction. Hawthorne writes about immigrants. So does Willa Cather. From the beginnings of literature, poets and writers have based their narratives on crossing borders, on wandering, on exile, on encounters beyond the familiar. The stranger is an archetype in epic poetry, in novels. The tension between alienation and assimilation has always been a basic theme.

Jhumpa Lahiri is always good in noting the particular. It requires a remarkable strength of observation, to detail and then recreate it in a different land. It could not be an easy task. Her detailing is restricted to the physical landscape, that is easily done, with a conscious practice of the art. it is conveying the atmosphere that takes discipline.

In The Lowland the story struggles to be heard between the vast passages of history lessons that the reader has to endure. It makes the novel very tedious to read. Probably it is due to the subject she has chosen — Naxalism. In the novel, her treatment of the movement is distant and unfresh neatened up in a story. For those familiar with the movement, in the 1960s, it was fairly simple in it being a peasant uprising launched by Charu Majumdar. (http://www.hindustantimes.com/News-Feed/NM2/History-of-Naxalism/Article1-6545.aspx). Today, the Indian newspapers are dominated by news emerging from parts of India affected by naxals. In an email to me about naxalism in India, Sudeep Chakravarti of Red Sun fame, writes “The maoist rebellion in low to high intensity can now be said to exist in between 106 districts. this does not include areas where propaganda and recruitment are on but as yet there is no conflict (for example, several indian cities, Haryana, Punjab). Numbers too are down. It is today a relatively more weakened force than, say, in 2006. but it’s a phase. the movement is nowhere near dead. I expect to take new shapes and strategies — in many ways that is already happening.”

Lowland is on the shortlist for ManBooker Prize 2013 and longlist of the National Book Award 2013. Jhumpa Lahiri’s talent has always been to tell a story, capturing the “thingyness of things”, but in Lowland she fails. One always lives in hope. At heart she is a good storyteller, but Lowland will not be her calling card as an author, that place is reserved firmly for Interpreter of Maladies.

3 Oct 2013

Jhumpa Lahiri The Lowland Random House India, India, 2013. Hb. pp. 350