Christina Lamb, “Our Bodies Their Battlefield: What War Does to Women”

In 2005, I had worked as part of a global team on a seminal report published by UNRISD called Gender Equality: Striving for Justice in an Unequal World. The particular section that I had researched was “Gender, armed conflict and the search for peace”. It was an extraordinary eye-opener for it highlighted the horrendous levels of violence perpetrated upon women and girls, across the world. Somehow conflict situations become an arena where the wild lawlessness thrives and the stark reality of the violence women experience is gut-wrenching. The women are treated worse than animals. Just flesh They are easily dispensed with once the women outlive their utility which in most cases is that of being sex slaves. The UNRISD report went a step further than merely discussing the violence but also documented the various methods of peace that were initiated by women or with the establishment of institutions such as Truth and Reconciliation Commissions and of course, the International Court of Justice.

Award-winning war reporter Christina Lamb in her book, Our Bodies Their Battlefield: What War Does to Women reports from various war zones around the world. She travels far and wide meeting women who have been victimised, abducted, raped, sold by one soldier to the next, etc. She met people like the Beekeeper of Aleppo, Abdullah Shrim, and Dr Miracle or Nobel Peace Prize winner, Dr Denis Mukwege, who have helped women. Or the incredible Bakira Hasecic, Association of Women Victims of War, who said her hobbies were smoking and “hunting war criminals” and she was not joking, having tracked down well over a hundred. Of these, twenty-nine were prosecuted in The Hague and eighty in Bosnia. Abdullah Shrim has rescued hundreds of women who were kidnapped by the ISIS and reunited them with their families. He has run extremely dangerous operations and created a vast network of safe houses and carriers who would help bring the women to safety. It has been at great economic cost to the women’s families, who at times have had to fork out sums as large as US $70,000. Dr. Mukwege, meanwhile, has helped reconstruct and fix women victims of sexual violence.

…either suffered pelvic prolapsed or other damage giving birth, or were victims of serial violence so extreme that that genitals had been torn apart and they had suffered fistulas — holes in the sphincter muscle through to the bladder or rectum, which led to leaking of urine or faeces or both.

In twenty years of existence, the [Punzi] hospital had treated more than 55,000 victims of rape.

He is recognised as having treated more rape victims than anyone else on earth. As a trained gynaecologist, he had set up multiple maternal hospitals around Congo so as to tackle the growing menace of maternal mortality, where women uttered their last words before going into labour as they were never sure if they would live. Once the Rwandan genocide occurred, Dr Mukwege, he began to help women victims.

Each group seemed to have its own signature torture and the rates were so violent that often a fistula or hole has been torn in the bladders or rectums.

‘It’s not a sexual thing, it’s a way to destroy one another, to take from inside the victim the sense of being a human, and show you don’t exist, you are nothing,’ he said. ‘It’s a deliberate strategy: raping a woman in front of her husband to humiliate him so he leaves and shame falls on the victim and it’s impossible to live with the reality so the first reaction is to leave the area and then is totla destruction of the community. I’ve seen entire villages deserted.

‘It’s about making people feel powerless and destroying the social fabric. I’ve seen a case where the wife of a pastor was raped in front of the whole congregation so everyone fled. Because if God does not protect the wife of a pastor how would he protect them?

‘Rape as a weapon of war can displace a whole.demigraohic and have the same effect as a conventional weapon but at a much lower cost.

The accounts in this book are meticulously documented. Christina Lamb even manages to speak to some of the victims. One of them, Naima, who had been abducted by the ISIS recalled the name of every single abductor she was sold to. It even astonished Christina Lamb that Naima was able to recall in such detail. ‘The one thing that I could do was know all their names so what they did would not be forgotten,’ she explained. ‘Now I am out I am writing everyting in a book with everyone’s name.’ Lamb travels and meets people in Argentina ( the Lost Generation and the Mothers and Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo), Nigeria and the Boko Haram, Bangladesh and the birangonas or brave/war heroine, the ethnic cleansing of the Muslims in Bosnia, the Rohingya camps of those who fled Myanmar, the Rwandan genocide between the Hutu and the Tutsis, the women abducted and kept by the ISIS, the former sex slaves of Japan or the rape of the German women by the Red Army during the Second World War etc. The list is endless and exhausting.

The graphic descriptions in the book are vile but most likely tamer versions of what was really said, shared or documented since it is impossible to collate it as is for a lay readership. The anger and revulsion that Christina Lamb feels and conveys in her documentation regarding the sexual crimes perpetrated against women is transmitted to the reader very clearly. The mechanical manner in which the women are raped over and over again, leaving the women numb and injured is blood curdling. It is also imbued with a sense of helplessness trying to understand how can this wrong be ever corrected — Why are women pursued in this relentless manner, used and discarded? Or even seen as war trophies. What is truly befuddling is the ease with which men rape women or conduct mass rapes. It is not only the systematic violence that is perpetrated upon the women but the horrifying thought that this attitude probably exists in a daily basis. Men see women as dispensable, as a sex that they have limitless and unquestionable power over and the authority and prerogative to do what they like. War crimes only bring to the fore that which already exists already. It is not a gargantuan leap of imagination by men that requires such methodical violence perpetrated upon so many women in this brutal and agressive manner. What is even more chilling from the facts Lamb unearths is the despicable manner in which the rapists are rarely convicted, and if they ever are convicted it is usually for war crimes. Their convictions are carried out on the strength of the ethnic cleansing that they perpetrated. The absolute lack of respect or value accorded to a woman survivor’s testimony, if some of the victims agree to testify, is atrocious. Instead as Bakira points out that if you do not testify it’s as if it never happened. “Women should be allowed to say things the way she wants, tell the story how she wants.” Unfortunately what emerges is that even the institutions of justice and remedial action are so patriarchal in their nature and construct that they do not wish to acknowledge the ghastly trauma women suffer. Chillingly “in Bosnia it’s better to be a perpetrator than a victim. The perpetrators’s defence are paid by the state while we [the women] have to pay our own legal costs. And there’s still no compensation for victims.”

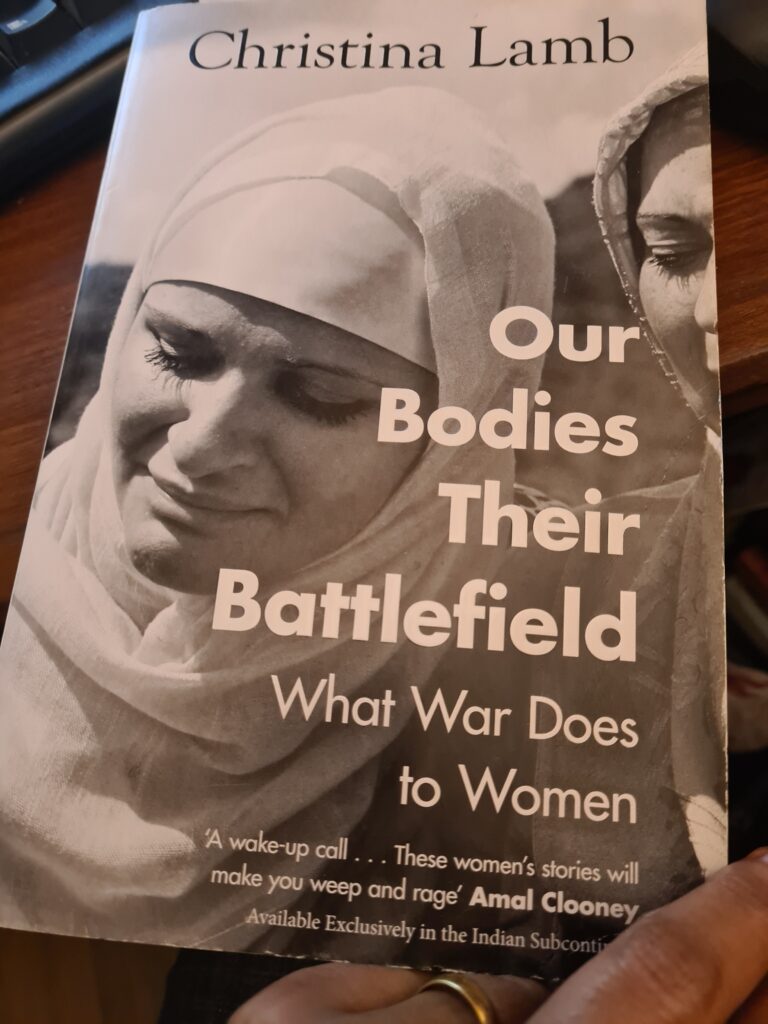

Our Bodies, Their Battlefield is not easy reading. There is a visceral reaction to reading the accounts. But as Lamb points out that this is a very dark book but she hopes that the reader too will find the “strength and heroism of many of the women inspiring”. She continues, “I use the expression ‘survivors’ to emphasise the resilience of these women, as after all they have survived, rather than ‘victim’ which has a more helpless connotation and some see as a dirty word. Meeting all these women, the last word I would use about them is passive. However, while I do not want to make ‘victims’ their identity, at the same time they are victims of an appalling brutality and injustice, so I do think the word has some validity. In some languages, such as Spanish, the word ‘survivor’ means survivor of a natural disaster. Colombian and Argentinian women I met told me it made no sense to refer to them as survivors. So I have used both where appropriate. In the same way, Yazidis told me they did not object to being described as sex slaves, as long as that was not seen as their identity.” Gender divisions are an age-old phenomena. Seeing women as loot, especially at times of war is also many centuries old. But the fact that these ugly, ruthless, mindless, violent practices continue to exist despite there being so many conversations about gender equality and sensitivity is extremely painful. It is as if those who believe in the dignity of women and in gender equality are expending energy on a losing battle. When will it stop? Will it ever cease? And surely these are learned behaviours and attitudes towards women, so how and when are the younger generations of men being indoctrinated and encouraged to behave in this abominable fashion? It is true that many men still believe firmly in the idea of masculinity being that when you prove your supremacy as an individual upon women, but seriously, can this old-fashioned attitude not stop? War zones are a stark reminder that these attitudes are not going away in a hurry. My only objection is to the cover design of this book depicting women wearing head scarves. Thereby signalling that the violent behaviours documented by Lamb exist more or less within one specific community, ie. the Muslims, who are equally conveniently seen as terrorists. This is wrong. The cover design should have been either an illustration depicting conflicts and different scenarios or had a montage of images from different regions and communities. This striking black and white image does a great deal of disservice not only to the community it represents but also to the book.

Nevertheless, please read this extremely powerful book.

25 Feb 2021