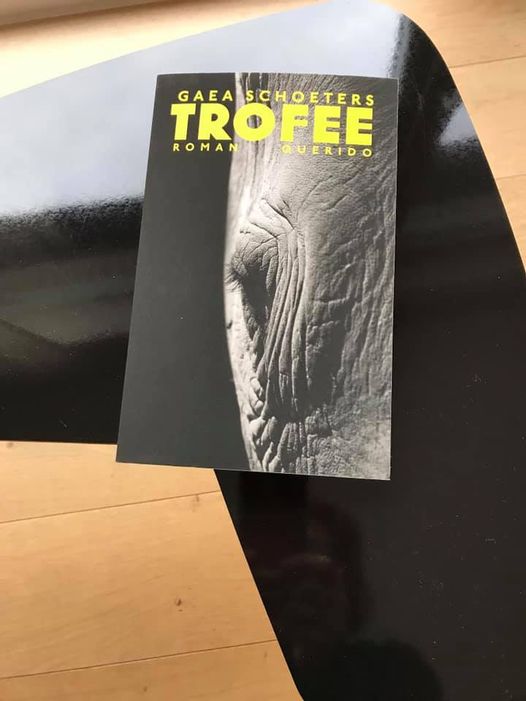

Interview with Flemish writer Gaea Schoeters

(c) Author photograph: Annelies Van Parys.

(C) EU

This interview is facilitated by EUPL and funded by the European Union.

I am posting snippets of my correspondence with Gaea as it would give readers an insight into how mind blowing her writing is.

Dear Gaea,

I like how you quote Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. One of my all-time favourite books.

Yet, I made many false starts with The Trophy. It is a very discomforting novel. The rhino charge is very real and it brought back memories for me. I was once in the Kaziranga Sanctuary, Assam with my father. The sanctuary was closed because of the monsoon, but we had been given access by the forest department. As a result, the place was devoid of tourists. It was quiet and lovely and my dad, who is an avid photographer, asked for the jeep to halt at one point, so as to take some pictures. As soon as the engine went silent, out came from the thick, long grass, a rhino. It was a new mum wanting to protect her calf which she thought was under threat. Everyone was startled. The driver tried starting the engine and it refused to. For a few seconds there was pin drop silence in the car as well as complete panic and then just as the large animal came out of the grass in a rush, the driver started the car and sped away. A very real “What if?” scenario. Unforgettable.

But it is more than about the rhinos, isn’t it? You explore so many ideas such as living museums, collectors, attributing a value to a thing (notional or real), etc. If I had read your book in print, it would have been thoroughly dog eared and underlined. It is hard to do so on a pdf. Thank you for sharing it. I hope one day you can bring it to India.

If The Trophy is anything to go by, I would definitely like to read your first book, Girls, Muslims and Motorcycles. Is it available in English? I read the brief on your website. In fact, years ago, I read All the roads are open: an Afghan journey, 1939-1940 by Annemarie Schwarzenbach, a writer whom you seem to have referenced as well.

Dear Jaya,

do not worry. Actually, from a writer’s perspective, I can only be overjoyed that my book elicited such strong feelings in you that provoked such a direct response. And even more so that you feel such a direct connection that it invites a correspondence which does not need further formal introduction – it seems the book was enough of an introduction. Or, if you look at it that way, a rather direct (and harsh) piece of reading that I dropped onto your reading table without warning.

So again. Do not worry.

I find your questions very interesting and want to answer them decently. (I’d prefer to answer them in depth rather then quickly, since you’ve clearly put some thought into them as well – and especially because the book has affected you so.)

Oh, and concerning your question about Girls, Moslims & Motorbikes – unfortunately it has not been translated yet, so I’m afraid I can’t help you there… but Schwarzenbach (& Maillart) were indeed a big inspiration; we followed their tracks and had their books with us while travelling.

Warm greetings!

Gaea

***

Gaea Schoeters (1976) is a writer, screenwriter, librettist and journalist. She made her debut with the travel book Girls, Muslims and Motorcycles about a seven-month motorcycle trip through Iran, Central Asia and the Arabian Peninsula. This was followed the novels Diggers (Manteau), The art of falling (De Bezige Bij) and Untitled #1 (Querido) and the interview-collection Het Einde (Polis). Her latest novel, Trofee, was shortlisted for various prizes and won the Sabam Prize for literature. With illustrator Gerda Dendooven she made Nothing (De Eenhoorn), a philosophical picture book for children young and old. With composer Annelies Van Parys she wrote several award-winning operas and music theatre pieces; their work is performed at venues such as Biennale Venice, Staatsoper Unter den Linden, Folkoperan Stockholm, Opera Ballet Vlaanderen, Deutsche Oper, Operadagen Rotterdam and Theater aan Zee. And in collaboration with Johanna Pas she translated Kae Tempest. All her work lies at the intersection of formal experimentation and social engagement. She is a much sought-after columnist and essayist for various newspapers and magazines, and the curator of the Dead Ladies Show, a café chantant that spotlights forgotten women.

Q1. Your portfolio resume says that you are a journalist, an author, a librettist, and a screenwriter. Why do you choose to make Art, with a capital “A”? Are all forms of art commercially viable for the artist? How do you balance making art, communicating ideas, and making a living?

I don’t think making art is a choice. I’m afraid I have to write — telling stories is who I am and what I do. All choices I have made in my life have always led me back to this point. It is my way of trying to understand life and the world we live in, and trying to influence it by sharing my ideas or insights with others. Art is to me, more than anything else, a form of communication. A way to raise questions and hope that readers reflect on them, or to confront them with their own feelings and prejudices. Literature is a spotlight that I can point at things, forcing people to look at them from a certain angle and making it impossible to look away. And contrary to other forms of writing, like opinions, art does not have to provide answers — always much less interesting than questions.

(The idea of becoming a writer shaped itself in my mind when I, still very young, saw the film Henry & June in the cinema: a biopic about Henry Miller and Anais Nin in Paris in the thirties. It presented ‘the author’ as someone who spent his or her life discussing the world, literature and philosophy sitting in bars all night long surrounded by beautiful women. To me, that felt like an attractive future, but my parents saw things differently, so I studied interpreting. After university, I enlisted for a journalism master and there one of my teachers told me I should write fiction, so I did an extra year of scriptwriting. But looking back at it now, I have actually never not written: literature was always there and thinking about the world and sharing these ideas through language is indeed what I do. However, the idyllic bar idea is in reality much less romantic — writing is hard work, especially if you want to live of it.)

Making a living of literature is, especially in a small language area like Belgium, nearly impossible. That I am able to live of my writing, is because I combine so many different things. I once calculated that one day of scriptwriting equals to one week of writing for the newspaper, one month of working for opera or theatre and one year of novel writing. So for a long time, I financed my novels with writing soap for television. Also, I (luckily) like to be on stage, so I do a lot of performances and created my own programme, the Dead Ladies Show, a café chantant where we honor important women from the past. All these things make it possible to live of my writing, in a very broad sense. And these collaborations are, very often, also artistically enriching.

Q2. Your website states that you prefer to work at the intersection of “formal experimentation and social engagement”. How?

For me every book needs a story, a theme and form. The one cannot exist without the other, and they have to be very closely linked. What sets literature apart from other forms of writing, is that it is not only crucial what it conveys, but also how. Explore the possibilities of telling narratives in non-classical ways is half of the fun. (We are obsessed with classical structures, driven forward by conflict and causality. This also shapes our (western) world view. But is this really the only way of thinking and of telling stories? Can different narratives create different ways of thinking, different ways of solving problems? Does art reflect the brain, or train it – or both?) I have, for example, tried to find out if it is possible to base the structure of a story on the structure of a musical piece ( a classical piano trio), by connecting characters to instruments and themes to musical themes and using the score as a building plan for the novel. It does work! It reads differently, less linear and with more repetition and variation, but I found it fascinating.

On the other hand, I am aware of the fact that I, as an artist, am at the same time part of the world / social reality that I live in, and, being an observer, also a privileged outsider. I don’t know if art can chance the world, but I am convinced that it can chance the lives of individual people. (If a book can touch one person to such an extent that it really impacts his or her life, it was worth writing.)

Also, I believe literature has the power to create empathy with ‘the other’. Maybe that is why I have a fondness for unpleasant characters or characters who are very different from myself; I feel a deep need to explore the mind of people with whom I’d probably get into a fight very quickly in real life. And to try and find out why they think what they think and do what they do. For me, fiction is a place where we can push ethic questions to the extreme to map their consequences, safely juxtapose different mindsets and try to find common ground which can be the beginning of a dialogue and of understanding — and therefor of change. (In the case of Trophy, a shared love of nature was the point of connection with the world of hunting and the character of Hunter.)

Q3. What prompted you to write The Trophy? Why do you use “Hunter” as a noun? Whereas in the context of the story, he is quite literally the hunter in pursuit of his game, his prize. It is a name, true. But, in the context of this story, it is unnerving. This is a very testosterone driven novel. How did you get into that mind space so as to write this story that is so white, male, masculine, and with a deep sense of colonialism*? Did it involve a lot of background research? ( * It is a brand of colonialism that is linked with those in the years gone by. Yet, this story is set in our contemporary world. It is unnerving.)

I know it is unnerving. I am sorry. I wanted it to be. I wanted to lure the reader into following Hunter’s thoughts and perspective, to be able to confront him or her brutally with the consequences of this white male gaze from within. I am aware it is a harsh read. But I think it is far more effective to make people feel this than to tell them from a safe third person perspective.

If anyone had told me five years ago that I would write a novel about trophy hunting in Africa I wouldn’t have believed it; I am the kind of person who catches mosquitos alive and carries them out to the balcony. I had no connection at all with hunting or trophies. But while scrolling on Facebook, I bumped into a small advertisement for a trophy hunt on a rare kind of ibex in Pakistan, announcing that a protection programme would be set up with the money from the hunting licences. This (hunting rare species as environmental protection) sounded so paradoxical that it stuck to me and I started to do some research on trophy hunting. Shortly after, I stumbled upon a photo by David Chancellor — an image of a large game hunter (a man who looked very much like my accountant) in his trophy room, walls lined with stuffed giraffes, lions, etc. I wanted to know who he was and why he did this, shamelessly. And then I read an article about the ‘relocalisation’ / ‘reintegration’ of a local group of San, using precisely the same words we use for reintegrating wolves and bears in nature. That shocked me — language gives away what we think: if we talk about people with the words we normally use for animals, that means we look at them in that way. In one split-second, the story formed in my mind.

I did two years of research on hunting, fauna, flora, guns, … emerging deeply also in discussions between environmentalists and hunters. I wanted to get every detail right. But above all, I wanted to get into Hunter’s mind. For that, I returned to an old genre (searching for the correct form was crucial) of old colonial ‘hunting literature’ where professional hunters describe their hunts in a very macho way, but (even though their vocabulary is very colonial) with a lot of respect for the local people they work with. This helped me understand Hunter’s way of thinking. And although we no longer live in colonial times, I am afraid many things are not so different nowadays. As Jeans puts it at a certain point: Hunter has never been to Africa. The place he visits is a colonial fata morgana, a white gaze fantasy with no relation to reality. He has no idea of the continent and no interest in it; he sees it merely as a theme park that exists for his pleasure. His hunting ground. (Or as he says himself: he doesn’t like Africa, but as he likes its wildlife, he tolerates the continent.) That is a crude summary of the common utilitarian Western view on the continent: even in these post-colonial times, the exploitation of the continent continues in a different form. (And not only by the West; a whole new Great Game is played out there.) Companies go on taking from the African countries the resources and riches they need, disturbing nature, climate and society, but refuse to take responsibility for the effects caused by this ongoing pillage.

Q4. Your seething rage is evident through sentences like this: Idiotic whites with their idiotic rules; Ethics, as Hunter has learned, has the same colour all over the world: that of the dollar; How one animal hunts another is none of our business, as humans. How did you remain calm, if at all, while writing this book? What has been the reception to this book?

As a writer I try to keep my personal anger out of a book — at least on the first level. I think it is more powerful to introduce the reader to all perspectives and let him/her walk to his own downfall. But of course, the whole book is an accusation of how ‘the West’ deals with the world, and my indignation about that was the trigger to write it.

Hunter, like most Westerners, sees himself as a morally superior to the local people, but isn’t aware of the fact that his moral ideas may not or cannot function in a world which is completely different. The West tends to want to impose its moral concepts on the rest of the world, without taking into account the local preconditions. Is ‘our’ system the only system, and is it really so superior? Does it work everywhere, in every context? (And how unaffected is this context? Jeans is a pragmatist, because he has no other option in a world disturbed by the effects of colonialism. And how free are the members of the local tribe in their choices, as the conditions of their existence have also been altered or determined by it?) Or could it be that other moral systems and ethical rules are equally valuable, or maybe even better, than the Western one, within certain contexts? It is this clash of thinking systems and their consequences that I wanted to explore.

Balancing my own feelings about things while writing is not easy. I always try to project my opinions into my characters, rather than letting them seep through in author’s comments — this way you make it part of the conflict inside the story. My anger is spread over Van Heeren’s cynicism, Jeans’ pragmatism, Dawid’s retained rage etc. But in order to make the story work, I also had to get inside Hunter’s head, and while I was there, I had to understand and even ‘love’ him, at least as much as he loves himself. I spent two years living with him, every day — that wasn’t always easy.

Many readers have told me that the book affected them deeply. That it stuck with them for days after reading. That they were shocked by how far they had followed Hunter’s logic and how close to him and his thinking they had come. I take that as a compliment. Also, many hunters have told me that for the first time, they felt understood. That, too, is a compliment. I wasn’t looking for black and white judgement, that is too easy. I wanted to describe things in all their complexity, and leave the conclusions to the reader.

Q5. So, like it or not, trophy hunting is the only form of rhino conservation that works, and the only chance the species has for survival. The six-figure sum he has paid to be allowed to shoot that single male is not only financing a breeding programme, but also giving the rest of the herd a fair chance of being protected. But that’s something these ‘conservationists’ don’t seem to be able to understand. This is a paradox. Is this really true in the field of conservation? Why is it not talked about more?

It is certainly true from Hunter’s point of view, and that is what counts for the story. In the real world it is more complex and debatable — I spent days reading well-researched discussions between ecologists, biologists and hunters about this theme. However, it is alas unquestionably true that within the capitalist logic and in a post-colonial Africa which is largely affected by (historically induced) corrupt or reigned by corrupt regimes, wildlife is only worth protecting when economical value is attached to it. Otherwise, it is more interesting to be bribed by poachers, or simply not a priority in poverty-struck countries to invest in wildlife protection – which is very understandable. Add to that the pressure on wildlife and ecosystems caused by overpopulation, poverty leading to small poaching and bushmeat being sold on the black market, etc. and you get an idea of why things are so complicated. (The discussion even goes to the point where wildlife parks and animal protection are called ‘ecocolonialism’ or ‘green colonialism’, which I also understand — if the pillage of natural richesses continues, it is a bold thing to impose Western green ethics (which we hardly apply closer to home) on a continent which Western companies continue to plunder.)

That it is not talked about, is probably because it is not our field of interest. The West only shouts scandal when an individual ‘cute’ animal is threatened, like when the American dentist shot Cecil the lion. There’s a certain hypocrisy to that, if one thinks of the ecological drama that is unfolding in the amazon forest or in the oceans due to climate change.

(I had a quick look at the situation in India and think that in spite of the strong hunting tradition in colonial times trophy hunting is now forbidden there, but I would have to check properly.)

Q6. Your writing mimics the pace and content of the story. Is it intentional?

I never start a novel without a clear idea of the theme and the form; for me these things are intertwined and the one cannot work without the other. Sometimes it takes years to find a form for an idea, or an idea that fits a certain form. This time I was lucky: during my research I found out that there is a (merely Anglo-Saxon) genre called colonial hunting literature. Very male and macho, adventure story like, fast and plot-driven, but also (in spite of the vocabulary which we now find unacceptable) very often full of rich anthropological observations and deep respect for the knowledge of the local people these professional hunters collaborated with. Think of writers like J.A. Hunter, or, on the more literary end of the spectrum, Hemingway. I believe that applying certain old forms or genres in new contexts is part of the dialogue of contemporary writers with the canon, which enables us to maintain an ongoing conversation with the literature and the literary tradition of the past. Using a colonial genre in a novel which is in fact a critique of this colonial past was the kind of irony that fitted my story perfectly — as Hunter is also driven to his destiny by precisely this old-fashioned view on the African continent. On the other hand, I wanted to make a link with Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness — but instead of the downfall of one white man driven to madness, I wanted to show the collapse of the alleged Western moral superiority in this collision of cultures.

Also, as the story is so extreme, I had to find a way to lure the reader into reading it fully once he’d started. So, I set it up like a trap: the increasing tension and increasing speed pull the reader deeper and deeper into the story, unable to let go, just like Hunter is pulled deeper into his hunt. I also wanted to create an increasing claustrophobic feeling, a darkness that wraps around the reader without him noticing it, but then suddenly surrounds him fully. I wanted it to be a trip-like experience, like a nightmare. And when Hunter’s world and logic starts to fall apart, I wanted the language to reflect that. I can only hope that it does.

Q7. How do you work with your translator? If you are proficient in English and Flemish, do you read and comment on the translation drafts? Do you edit them? Or do you accept the translation as it is from the original language to the destination language?

I tend to work closely together with my translators, even if I don’t speak or read their language. I’m trained as a translator myself and I still love to do it from time to time because it forces you to a very close and analytical reading of another writer’s work, which is very interesting for me as an author too. I occasionally translate poetry and plays, so I am very well aware of how valuable and how difficult translators’ work is. I never edit them, as I can never be as precise as a native speaker, but I try to be available to answer their questions. Sometimes things are just unclear, or you cannot directly transfer them into a different language without loss — then it is nice if you can search for a good solution together. Also, I think translators should be valued more, and their name should be on the cover of the book — in a foreign language you are only as good as your translator, and in the best case, they even make your book better.

Q8. Is climate-fiction and eco-fiction an essential contribution of writers to literary canons? How effective are they in raising social awareness?

We should all write about what moves, worries or amazes us, and I think climate is right now such an essential part of our times that it comes up automatically. Literature always reflects the time segment it is written in, and climatological change is so omnipresent that it will sneak into all books soon, even very unpolitical love stories. If this can help raising awareness I don’t know; very often people who read fiction are already on the more informed and aware side of the spectrum. (One cannot deny that (having access to) literature is very often still a privilege.) But were it can certainly change things, is in youth literature and in schools. I really believe in the formative power (also as a builder of empathy) of literature and art education.

Secondly, I think it can help us to look at ecological issues in a more open way, as fiction escapes the political / ideological frame in which most discussions take place. The public debate sticks to the capitalist viewpoint and very rarely thinks outside that box. Dystopic and utopic literature and scifi can easily escape this and think beyond this frame or question it. In a way Trophy, as a thought-experiment, also operates in this ‘free zone’.

Is it planetary fiction? Not consciously, but it can be read as such. As (eco)philosopher Val Plumwood put it: trouble began when people stopped considering themselves part of the food chain and put themselves above nature instead of seeing themselves as part of it, both hunter and prey. (Plumwood, just like Hunter, got a rude wake-up call when being nearly eaten by a crocodile.) In this way, Hunters vision on hunting (even though he, like many hunters, is much closer and in a more natural relation to nature and his food than most modern people) differs from the perspective of the local hunters, who see themselves as part of the ecosystem, instead of a species superior to it. The borders fade when Hunters feeling of mastery and superiority begins to fall apart when he is confronted with the brutality of wild nature, and realises his survival depends on coexistence and respect instead of human dominance, as his gun cannot protect him against this force. This change of perspective has moral and practical consequences, both good and bad – if these concepts make sense in this context at all. That is, if you want, a metaphor you could apply on our relationship with the planet.

Q9. Why do I get the impression that you are writing this text almost as if you can see every scene clearly in your mind’s eye and then are writing out the details. Did you see a lot of films and documentaries before writing The Trophy? Or is it your screenwriter skills that come to the fore?

To be honest: the story appeared in my mind as a film first. But time has taught me that film is an expensive and very slow medium when it comes to financing, and very often stories and ideas are trimmed by producers’ wishes and financial realities. So I decided to write the novel first; we can always turn it into a film later (and there is quite some interest for that). But while writing, I saw the characters and the scenes before my eyes, like in a movie; if I got stuck, all I had to do, was watch and write down what I saw. (Also, I’m not sure it would be a film I’d be able watch in the cinema. It has a tension and a harshness, even a cruelty, that I can bear on paper, but would find very difficult to watch on a screen. And writing it down had one other big advantage: I could really chose to stick to Hunter’s perspective and tell everything through his eyes. Such a viewpoint is much more difficult in film, but it was somehow crucial to how I wanted to tell this story. — because it’s precisely that choice that turns this story into a critique on white gaze.

Q10. Do you have any Flemish author/book/literary website recommendations for readers?

That’s a difficult question, I’ll try to aim a bit for books which – I think – are translated. Luckily, we have very good illustrators, whose works doesn’t need translation, like Peter Van den Ende’s wordless book De zwerveling or the fantastic Gerda Dendooven with whom I made a wonderful philosophical book, Nothing. The poet Paul Van Ostaijen is something special, and so is Louis Paul Boon — a bit of a national monument. And I’m a keen reader of Harry Mulish, but he was Dutch. As far as contemporary writers are concerned, I really like the absurdistic work of my colleague Annelies Verbeke, who writes great theatre texts and short stories. And I’m very fond of the work of Jacqueline Harpman, maybe Belgium’s best writer ever, who originally published in French. Doeschka Meijsing is interesting too, but she’s also Dutch. It’s also not a coincidence that I named more female writers than male colleagues; all too often the opposite is the case. That brings me to an interesting website: the female writers’ collective Fixdit has made really cool podcasts about female Flemish and Dutch writers, unfortunately only in Dutch. But we’re also aiming to set up an international network of female writers, and for that it would be great to include women writers from allover the world!

Disclaimer: This paper was written under the European Union Policy & Outreach Partnerships Initiative with the view to promote European Union Prize for Literature awardees. The publication was funded by the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.