Visiting International Publisher’s delegation, Sydney ( 29 April – 5 May 2019)

From 29 April – 5 May 2019 I was invited by the Australian government and the Australia Council for the Arts as a member of the Visiting International Publishers (VIPs) delegation. It is an annual event organized by the Australian government to coincide with the Sydney Writers Festival. The delegation consists of prominent publishing professionals from across the world, most of whom are associated with well-established publishing firms and agencies. Those interested have to apply for the programme.

It is approximately a week-long event with the intention of giving the visiting delegates a bird’s eye-view of Australian publishing. During the trip, the visitors are taken to various publishing houses, bookstores and interactions are set up with prominent authors and publishing professionals. Two days of the trip are set aside for most of the visiting publishers in the delegation for B2B meetings with Australian publishers. The idea being that for most of the local publishers it is not easy to go abroad for meetings but it is preferable to go to Sydney. It is such a well-managed event by the Australia Council for the Arts where every delegate has a customized programme while certain events such as visits to publishing houses and literary receptions are open to all.

It is the extraordinary understanding of the Australian publishing landscape that makes this trip so precious. Australia is not an easy continent to reach as it requires many hours of travel from any part of the world. Australia is a very rich and diverse nation with the First Nations people, the descendants of the colonisers and of migrant communities. This makes for a fascinatingly diverse mix of languages, faiths and cultures to be represented through its literature. A statistic that I heard while in Sydney was that now more than 30% of the population does not have English as its first language. These are some of the factors that contribute to making the robust Australian publishing industry. Unfortunately much of the local literature is not easily available across the world as the rights are inevitably linked with Commonwealth Rights. This effectively means that the global sale of the bulk of Australian literature is usually decided by the UK publishers who either represent or license the Australian titles. Of course this does not include well-known writers like Markus Zusak, Richard Flanagan, (now) Coetzee, Alex Miller, Kate Grenville, Charlotte Wood, Aaron Blabey, Andy Griffiths etc. And there are plenty more to add.

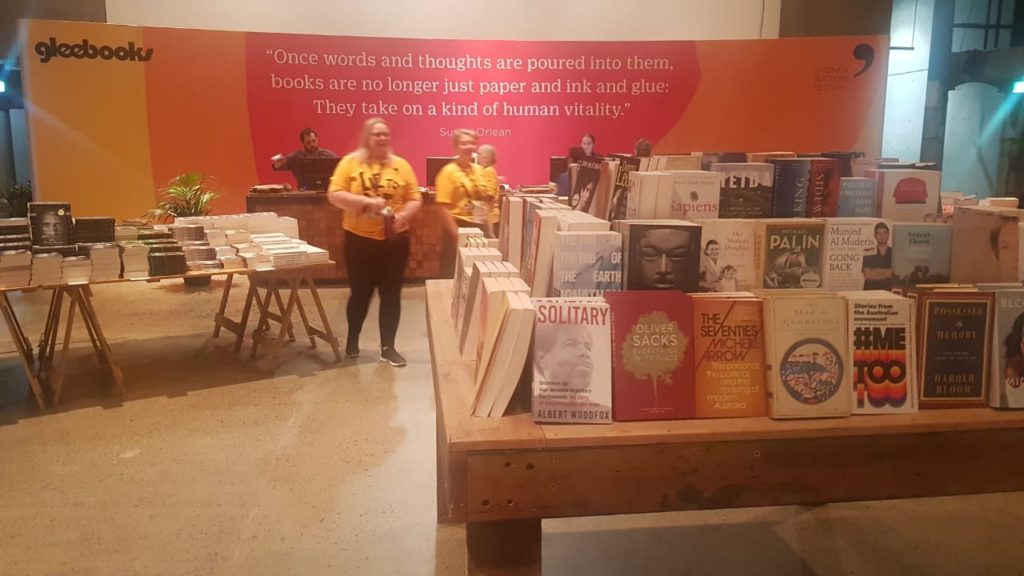

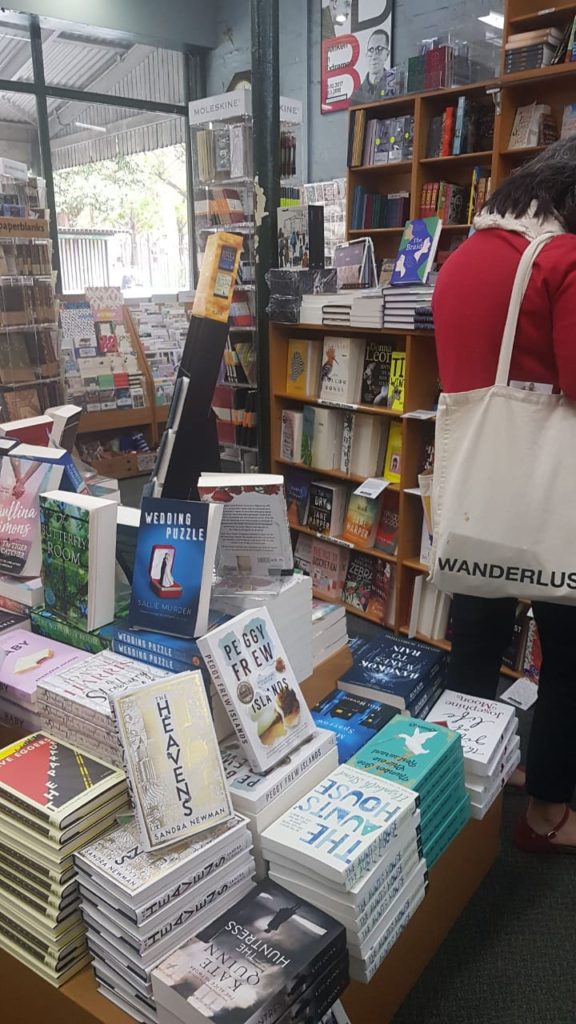

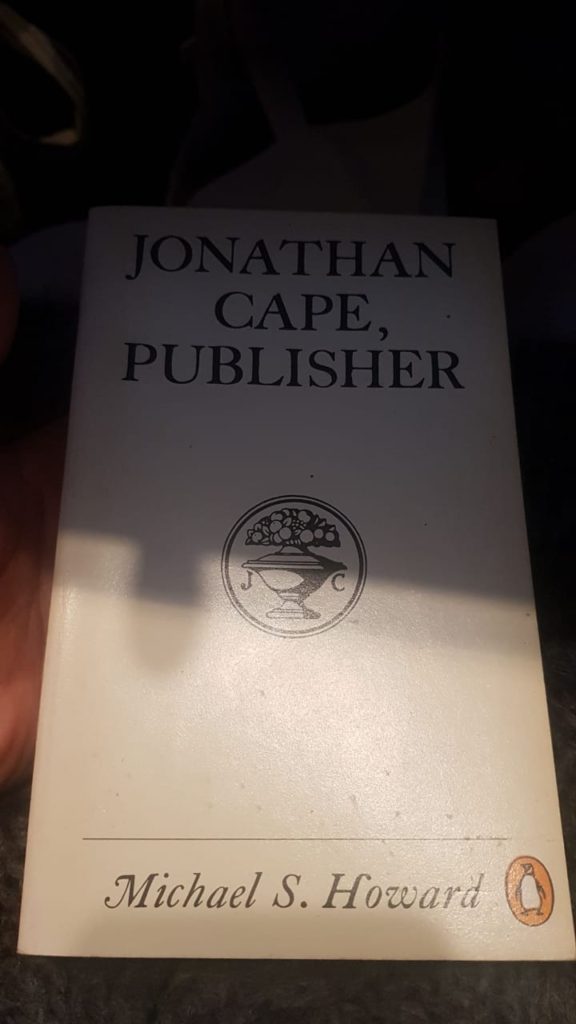

We were taken to visit a Gleebooks bookstore where award-winning writers Charlotte Wood and Morris Gleitzman addressed our delegation. They shared their experiences about publishing locally and then taking their works overseas. Gleebooks has a wonderful display of books but they also have a second-hand section where I was fortunate to pick up a 1970s yellow Penguin paperback history of Jonathan Cape.

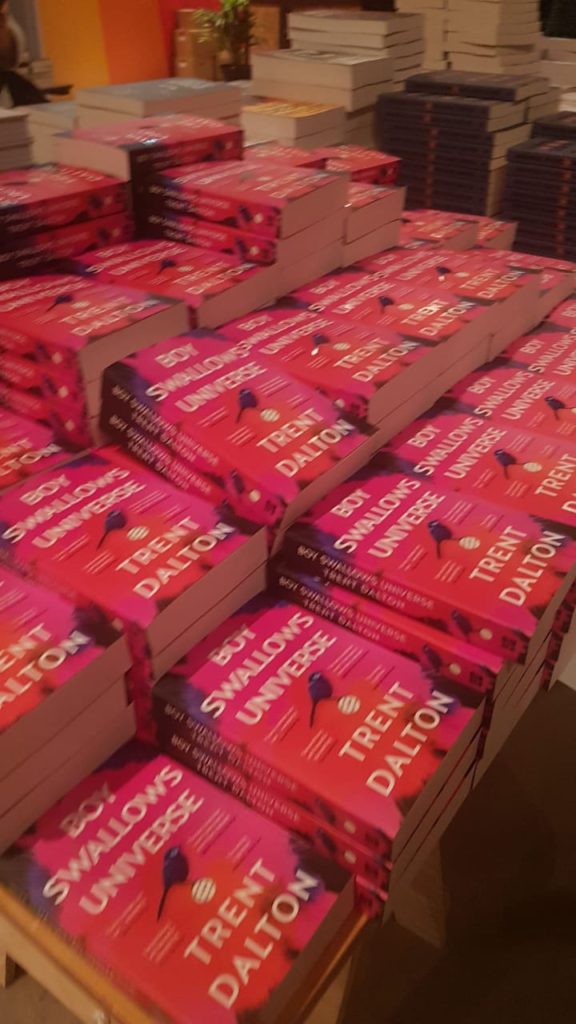

Books in Australia have GST, making them quite expensive to procure. Yet, it was amazing to watch how the tables stacked high with books at the Sydney Writers Festival bookstore disappearing rapidly. An incredible sight was to witness a table piled with multiple columns of first-time author Trent Dalton’s Boy Swallows Universeon the opening night of the literary festival. A day later when he had won a record four Australian Book Industry Awards and the overall Book of the Year crown with his smash hit coming-of-age novel, there were hardly any copies of the novel left on the table! Astounding! Price was no bar. The magic wrought by a literary prize had done its trick. Notched up magnificent sales for the author.

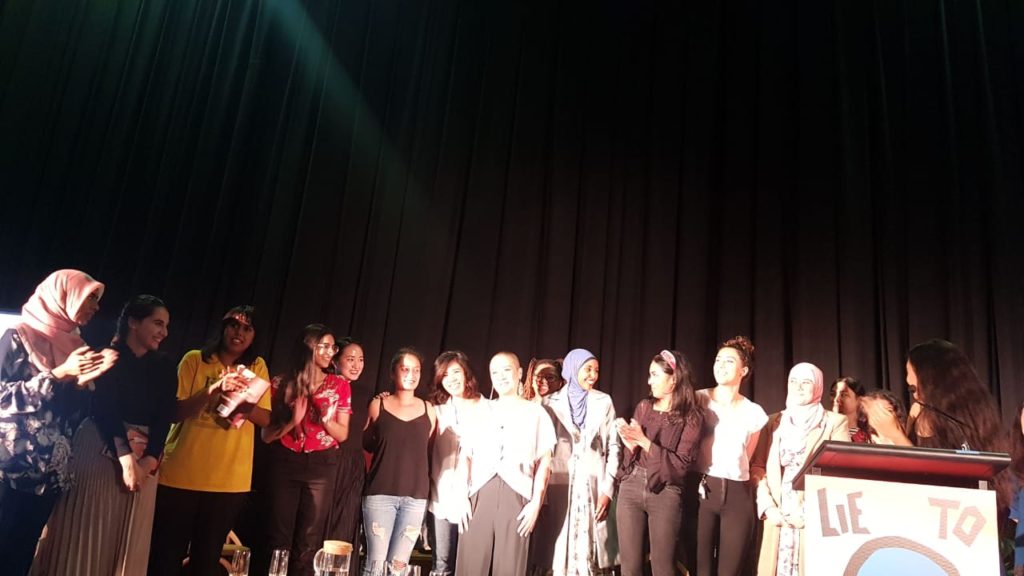

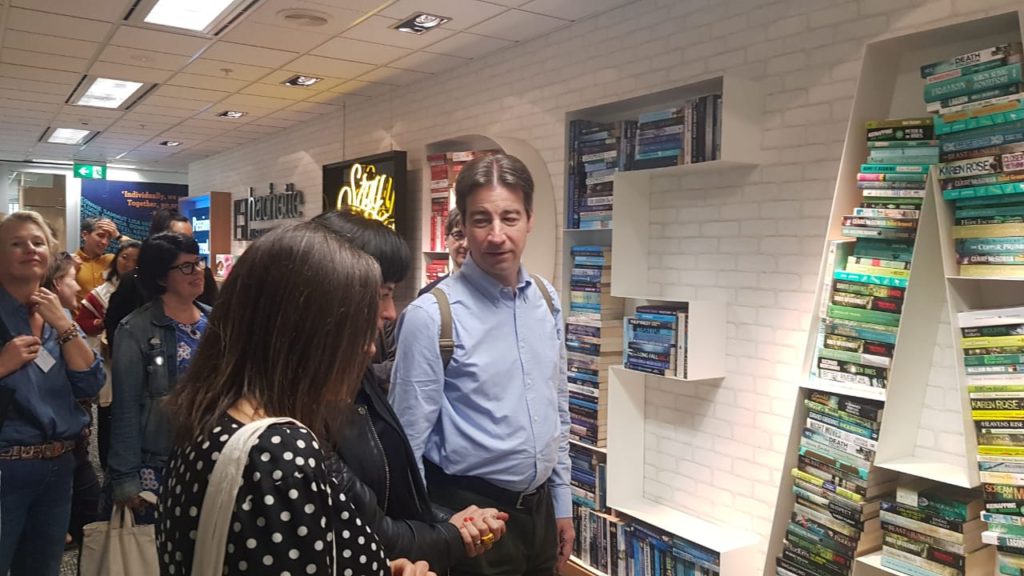

It is fascinating to witness how diverse Australian publishing is in terms of the lists that were showcased in each publishing meeting. There are distinct lists with emphasis on creating titles before the holidays and looking specifically at Christmas sales. While the big multi-national publishers like HarperCollins Australia and Hachette Australia exist with an impressive stable of authors and illustrators, it is equally important to note the presence of many indie and university publishers. Some of the university presses have been in existence for decades. Unlike rest of the world where such presses would be associated with only academic publishing, the Australian university presses have distinct trade lists catering to a general reading public. These lists consist of very distinct local voices that are representative of their society. For instance, there is some literature now being publishing looking specifically at the Stolen Generation. This refers to the time when aboriginal children were removed by governments, churches and welfare bodies to be brought up in institutions, fostered out or adopted by white families. But it is the indie presses and literary magazines that are representing the diversity which exists in Australia today. Perhaps, as happens with such initiatives worldwide, there is the enthusiasm to make available a wider range of stories as well as nurture local literary talent. So there are magazines for literary prose and others for poetry. There is literature representing the immigrants who are now Australians and see Australia as home while being acutely aware of their or their parent’s country of origin. In fact, at the Sydney Writers Festival, the Western Sydney Literacy Movement launched Sweatshop Women, their first-ever collection of short stories, essays and poems developed exclusively by women of colour from Western Sydney. It was a privilege to witness this launch as was evident by the exuberance of the contributors on stage. The range of writings in the issue are worth looking at too!

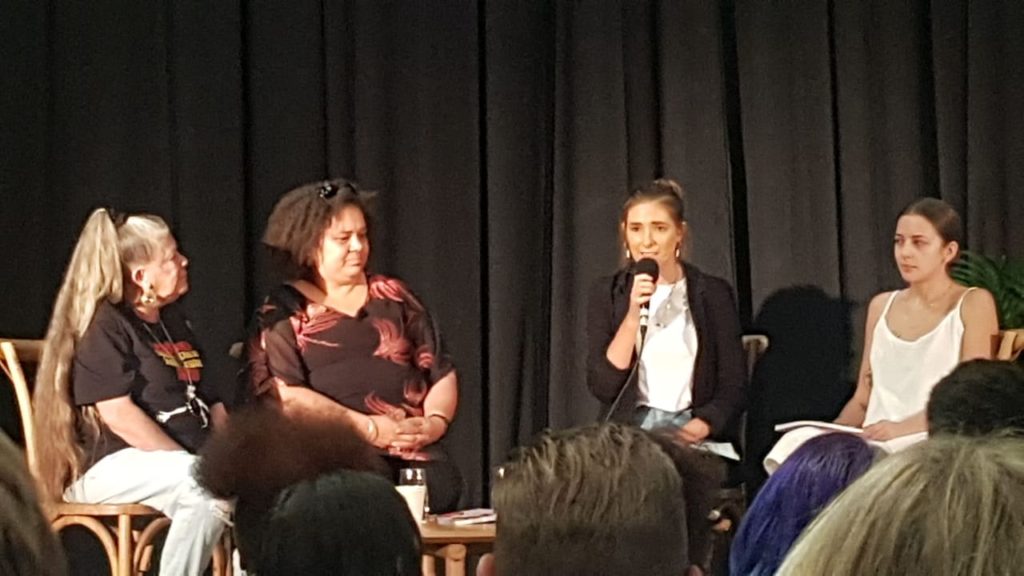

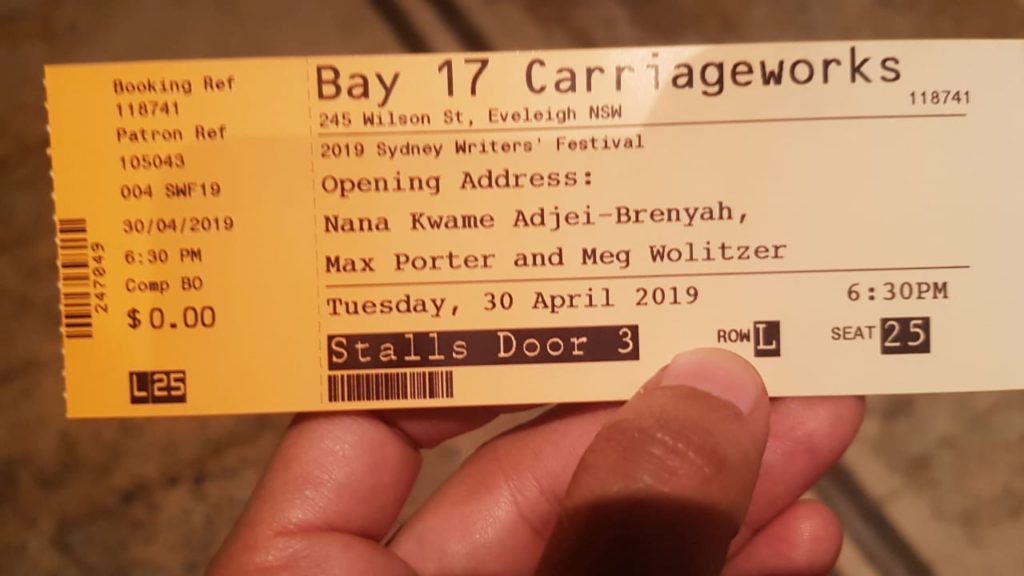

The Sydney Writers Festival is currently spread across some venues in the city while their regular venue is being renovated. There is such an exciting mix of speakers, a wide range of topics being discussed or being able to watch Richard Flanagan in conversation with Jenny Erpenbeck or even Roanna Gonsalves in conversation with Fatima Bhutto are treats. In fact, many of these conversations are available as podcasts on the festival website. A good literature festival is synonymous with sparkling, thought-provoking conversations, and this festival is definitely amongst the top-rated litfests. It began with the stupendous opening address by writers Max Porter, Meg Wolitzer and Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah. There were unexpected moments of joy of meeting literary stalwarts like Booker winner George Sanders, interviewer and curator Paul Holdengraber and other writers like Omid Tofighian, Alexander Chee, Max Porter etc.

A significant moment of the trip was to attend a dinner hosted in my honour by the Australian Council for the Arts to meet an energetic, creative, bunch of writers, filmmakers, poets, playwrights, and novelists who were mostly of South Asian origin. It was one of those very thrilling moments to discover that there were like-minded individuals equally enthused with publishing as I was. There were so many stories to share and familiarise oneself with regarding Australian literature. The one strong memory I have of all those many months ago was the electrifying energy around the dinner table while all of us chatted. The interaction around the dinner table that night confirmed was that the definition of “Australian literature” is far more diverse than what is made visible globally. And it is precisely through such active engagements by the Australia Council for the Arts that these very clear distinctions in literary trends are made visible.

During the short and intense trip to Sydney I met some very interesting people and was fortunate to be able to interview some of them for my blog. For instance, literary scout Rebecca Servadio and Susan van Metre, Executive Editorial Director, Walker Books. I also met librettist Tammy Brennan who was bringing her international production Daughters Opera to Delhi from 3- 5 January 2020. We ended up collaborating on the programme.

Later I was invited by the Australian Council for the Arts to address the visiting Australian delegation on “The Art of Interview”. The delegation was visiting India in Jan 2020 to attend various literature festivals. The delegates included sports journalist Gideon Haigh, writer and academic, Roanna Gonsalves, performance poet Manal Younus, poet Mindy Gill and literary festival director and artist Jessica Alice. It was an exciting and slightly daunting thought to be invited to address such eminent and experienced interviewers themselves but the evening went off swimmingly well. We were able to discuss the nature of interviewing in the modern age, how to use technology, is it helpful or intrusive, how to manage the tenor of a conversation, what is the nature of a public interview — is it like a theatre performance or a genuine interest in knowing the person, how does the written interview differ from the spoken interview, how much is enough to reveal in an interview, how much research is required to conduct an interview etc. Later in the evening we were joined by poet, writer and 2020 International Booker Prize jury member, Jeet Thayil.

The visit to Australia was a transformative experience. Suddenly a lot of pieces in the puzzle regarding the business of publishing in Australia became crystal clear. For facilitating this trip and actively encouraging me to visit their country I have am ever so grateful to the Australian High Commission in India, especially to the High Commissioner, H.E. Harinder Sidhu. In recent years the High Commissioner and her team in India and the Australia Council for the Arts have been actively promoting bilateral cultural ties between the two countries. Here is hoping that in future there will be more opportunities to make Australian literature available in India and vice versa.

6 Feb 2020