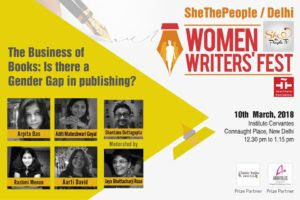

Panel on “The Business of Books: Is there a Gender Gap in Publishing?”

( Update: An expanded version of this blog post was published by Times of India on their website on 16 March 2018.)

To celebrate Women’s Day, ShethePeople organised a day long Women Writer’s Fest at Instituto Cervantes, New Delhi on Saturday, 10 March 2018. There were a range of fascinating panel discussions organised. I was moderated the midday session on “The Business of Books: Is there a Gender Gap in Publishing?”.

The panel consisted of eminent publishers such as: Aarti David, VP – Publishing, SAGE India; Shantanu Duttagupta, Head of Publishing, Scholastic India; Arpita Das, founder Yoda Press and co-founder Authors Press; Aditi Maheshwari-Goyal, Director, Copyrights and Translation, Vani Prakashan; and Rashmi Menon, Managing Editor, Amaryllis. The panel was a good representation of different kinds of publishing as they exist in India/ world today. SAGE is a multinational firm specialising in HSS (Humanities and Social Sciences) academic books and journals. Scholastic is a multinational firm specialising in children’s literature and is widely known for its direct marketing initiatives like school book fairs. Amaryllis is the English language imprint/firm launched by the Hindi publishing firm Manjul. Manjul Publishing is known globally for publishing the Hindi translation of Harry Potter. Recently Amaryllis announced its collaboration with HarperCollins India to distribute their books. Vani Prakashan is a family-owned business specialising in Hindi literature across disciplines and was established by Aditi’s grandfather. They also publish translations of international literature. Yodakin is an independent publishing firm co-founded by Arpita specialising in gender, social sciences academic books. They were the first to launch an LGBTQ list in India. A couple of years ago they announced a collaboration with SAGE India to co-publish titles. She is also the co-founder of a self-publishing firm called Authors Press.

The conversation which ensued was fascinating with anecdotal experience about publishing. Aarti David spoke of her  entry into publishing after being told by a HR consultant that now she was the mother of a two year old child it would be very difficult for her to get a job. Fortunately the person who interviewed her at SAGE India for the post of an executive assistant was the legendary publisher, late Tejeshwar Singh. After the interview he offered her a post in the marketing department. She has never left the firm. In fact there is gender parity at SAGE evident at the senior management level too. Of course as Arpita pointed out this has to do with the insititutional culture given that one of the co-founders of SAGE is

entry into publishing after being told by a HR consultant that now she was the mother of a two year old child it would be very difficult for her to get a job. Fortunately the person who interviewed her at SAGE India for the post of an executive assistant was the legendary publisher, late Tejeshwar Singh. After the interview he offered her a post in the marketing department. She has never left the firm. In fact there is gender parity at SAGE evident at the senior management level too. Of course as Arpita pointed out this has to do with the insititutional culture given that one of the co-founders of SAGE is  Sara Miller McCune.

Sara Miller McCune.

Rashmi Menon asserted that this was a complicated topic as depending upon which layer of publishing function one viewed there were gender gaps to be seen. For instance in her experience gender gap was noticeable in every top layer of management but much less in the editorial departments of a publishing firm.

Arpita Das was very clear that a gender gap existed as she rightly pointed out, “Always ask who controls the money?” She too shared some powerful examples of how gender equations work within firms and the publishing eco-system. Unfortunately in her experience after many years of being a publishing professional none of these deeply embedded attitudes have disappeared or are showing any signs of lessening. To illustrate this point she spoke of the male messenger in her first publishing job who had been entrusted with the task of taking their final manuscripts to the printers. At the time of handover this person would stare at the chest of the editor who inevitably was a female. Once Arpita called him out and asked him to look directly in to her eyes and speak. Ever after that all her handovers to the printer had mistakes. Even now, years later, she finds that these scenarios are repeated with her younger colleagues and she is still having the same arguments.

Shantanu Duttagupta was the only male publisher in a women dominated panel. He was also the only publisher to be representing children’s literature which is more often than not viewed largely to be the purview of women editors. He was clear from the outset that the gender gap in their firm is rapidly narrowing. In fact according to a recent statistic released by their HR department nearly 60% of their employees are women. This includes departments that are otherwise not viewed traditionally as women-oriented roles like production, accounts, and sales. He also reiterated that in his opinion this gender gap was in all likelihood being corrected by the ever growing list of books by women where the gender role plays were being discussed, demonstrated and subverted. Classic example of this being Scholastic’s bestseller the Geronimo Stilton series that are written by an Italian woman and then translated into multiple languages.

Aditi had a fascinating perspective to share. Vani Prakashan traditionally sells in the Hindi-speaking belt of the states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. In her experience publishing firms established outside the metros in tier-2 and tier-3 towns as well as in the villages are increasingly being managed by women. They are even responsible for printing, publishing and promoting their books. Selling it in the market while balancing a baby on their hip. Nothing deters them from continuing with the business of publishing books. Even at their own firm it is her mother who is responsible for ensuring the GST is filed on time, the office is opened on time, all branches of the firm work efficiently with the employees clocking in on time and leaving on time too. Her mother plays an integral part of the daily running of the firm. But as Arpita pointed out that in many family owned business the role of the woman gains importance which may not necessarily be the case in corporate systems.

After listening to the various perspectives I shared my own experience in the industry. I shared how in the past nine months since the new taxation policy of GST ( 1 July 2017) was announced it has become amply clear how the business lines in this industry are divided. I say this from personal experience at having witnessed and/or participated in events that have been about the business of publishing. Soon after GST came into effect I chaired a panel discussion of tax lawyers with publishing professionals. For the first time in my career (and I have been associated with this industry since the early 1990s) I witnessed a gathering representing finance, production, and editorial. There were people from independent publishers to multinational firms. There were self-publishers. There were language publishers. There were trade, children’s literature and academic publishers. Both men and women were present with men outnumbering the women. In the past year whenever I have attended policy meetings, had conversations about the business of publishing, attended the recently concluded 32nd International Publishers Association Congress and researched for my reports on the book market of India, I have inevitably come across more men than women in key decision-making positions. By “key” I mean designations where the professionals have the authority to comment upon their firm’s business models, income-generating streams, focus on business of making money in an industry which traditionally survives on razor sharp profit margins or those who are at a liberty to speak on behalf of their companies. Having said that there is a perceptible shift in this gender composition of firms to see women workforces in accounting, sales, and production departments and some are distributors and buyers for book retail chains and increasingly men in editorial departments. This gender disparity is “reversed” where the feminisation of the creative side the publishing ecosystem is visible. Increasingly there are more and more women writers, translators, designers, freelance editors, typesetters, reviewers, bloggers, publicists, and booksellers. These creative spaces are where there is less money to be made upfront. Also it is work that can be done juggling other responsibilities like domesticity and caregiving. This part of the workforce is as critical as all the other aspects listed above but is underpaid because a) they are perceived as being a part of the gig economy and b) because of an inherent gender bias their labour is undervalued since the costs of production are “contained” within reasonable limits. After all the end product, i.e. the book is a price sensitive commodity, even though in my humble opinion every single book is akin to being a design product and needs to be recognised in this manner. Frankly everyone ( irrespective of gender) involved in this publishing ecosystem needs to recognise the importance of being critically aware of how the business of publishing needs to be aligned severely with the creation of books and knowledge platforms. It is probably then that some form of gender parity may begin to creep into the industry. Green shoots of it are already noticeable with some key positions being held by women. Having said that feminisation of the editorial and creative community continue to exist. To my mind this appalling given how the evaluation of this industry is growing in leaps and bounds. According to the latest figures released by Nielsen Book Scan the Indian Book Market is valued at $6.5bn. This is an industry that creates something of value based upon the creative output of others, ie the authors.

are divided. I say this from personal experience at having witnessed and/or participated in events that have been about the business of publishing. Soon after GST came into effect I chaired a panel discussion of tax lawyers with publishing professionals. For the first time in my career (and I have been associated with this industry since the early 1990s) I witnessed a gathering representing finance, production, and editorial. There were people from independent publishers to multinational firms. There were self-publishers. There were language publishers. There were trade, children’s literature and academic publishers. Both men and women were present with men outnumbering the women. In the past year whenever I have attended policy meetings, had conversations about the business of publishing, attended the recently concluded 32nd International Publishers Association Congress and researched for my reports on the book market of India, I have inevitably come across more men than women in key decision-making positions. By “key” I mean designations where the professionals have the authority to comment upon their firm’s business models, income-generating streams, focus on business of making money in an industry which traditionally survives on razor sharp profit margins or those who are at a liberty to speak on behalf of their companies. Having said that there is a perceptible shift in this gender composition of firms to see women workforces in accounting, sales, and production departments and some are distributors and buyers for book retail chains and increasingly men in editorial departments. This gender disparity is “reversed” where the feminisation of the creative side the publishing ecosystem is visible. Increasingly there are more and more women writers, translators, designers, freelance editors, typesetters, reviewers, bloggers, publicists, and booksellers. These creative spaces are where there is less money to be made upfront. Also it is work that can be done juggling other responsibilities like domesticity and caregiving. This part of the workforce is as critical as all the other aspects listed above but is underpaid because a) they are perceived as being a part of the gig economy and b) because of an inherent gender bias their labour is undervalued since the costs of production are “contained” within reasonable limits. After all the end product, i.e. the book is a price sensitive commodity, even though in my humble opinion every single book is akin to being a design product and needs to be recognised in this manner. Frankly everyone ( irrespective of gender) involved in this publishing ecosystem needs to recognise the importance of being critically aware of how the business of publishing needs to be aligned severely with the creation of books and knowledge platforms. It is probably then that some form of gender parity may begin to creep into the industry. Green shoots of it are already noticeable with some key positions being held by women. Having said that feminisation of the editorial and creative community continue to exist. To my mind this appalling given how the evaluation of this industry is growing in leaps and bounds. According to the latest figures released by Nielsen Book Scan the Indian Book Market is valued at $6.5bn. This is an industry that creates something of value based upon the creative output of others, ie the authors.

So yes, I sincerely believe there is a gender gap in publishing, particularly when it comes to the business of books. There are many, many more strands I can pick up in this discussion but due to constraints of time I am unable to do so.

All said and done it was a fabulous session that according to the wonderful organisers, Kiran Manral and Shaili Chopra, not only went down well with the audience but also gained a lot of traction over social media. If it had not been for the competent emceeing of Saumya Kulshreshtha we would have continued chatting on stage for hours. There is so much to say on the topic!

13 March 2018