Interview with Priya Kuriyan

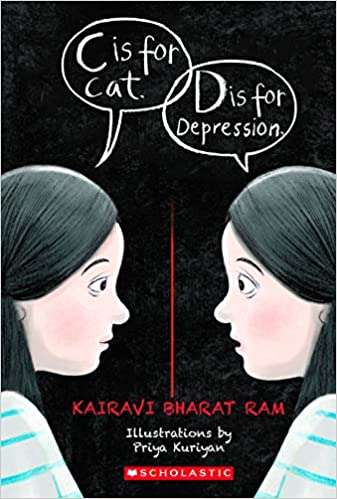

Mental health and related topics are at the best of times taboo subjects in India. To discuss openly about depression amongst teenagers/adolescents is unthinkable. In a country where being in therapy is still a hush-hush topic, to commission and publish a book on the topic is bold and that too in an experimental form — an illustrated memoir in rhyme. C is for Cat, D is for Depression ( Scholastic India, 2020) is a much needed book for young adults in helping to break barriers about mental health and make it a socially acceptable topic to discuss openly and without any stigma.

Kairavi Bharat Ram is a young published author who is known for her previous books in rhyme — Ramayana and Krishna. Those were retellings of Hindu epics. But this is the first time she has told a story about her personal experience of battling depression as an adolescent. It is a powerful testimony to the challenges she faced. It is a vivid description of all that a patient afflicted by depression experiences and is unable to always share clearly. At the same time, it is a gentle request to caregivers of such individuals to be patient and offer a caring hand whenever required. She also equally gently plots out methods in which the person themselves or those around them can help an individual come to terms with depression and related mental health issues.

This is a precious book. A conversation starter and a handy tool for anyone interested in mental health. It should become an essential requirement in every classroom and school library.

Hopefully this will lay the foundation for a strong and well-defined yalit list on mental health in India/South Asia. Kudos to Scholastic India for publishing this book!

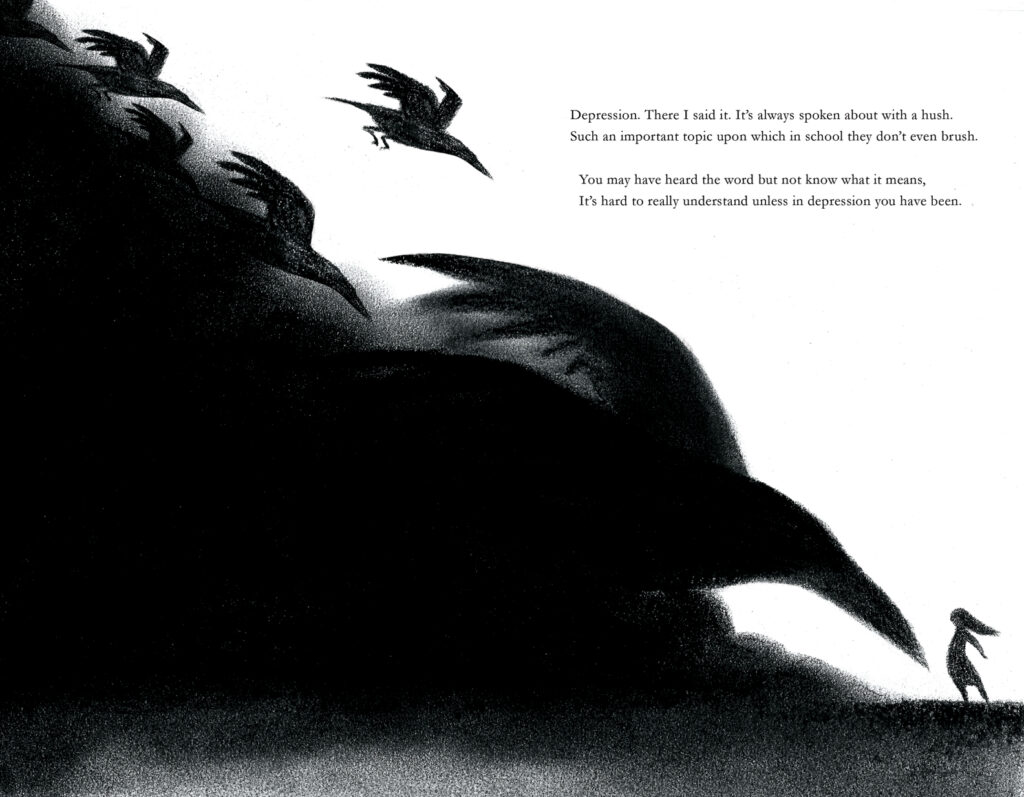

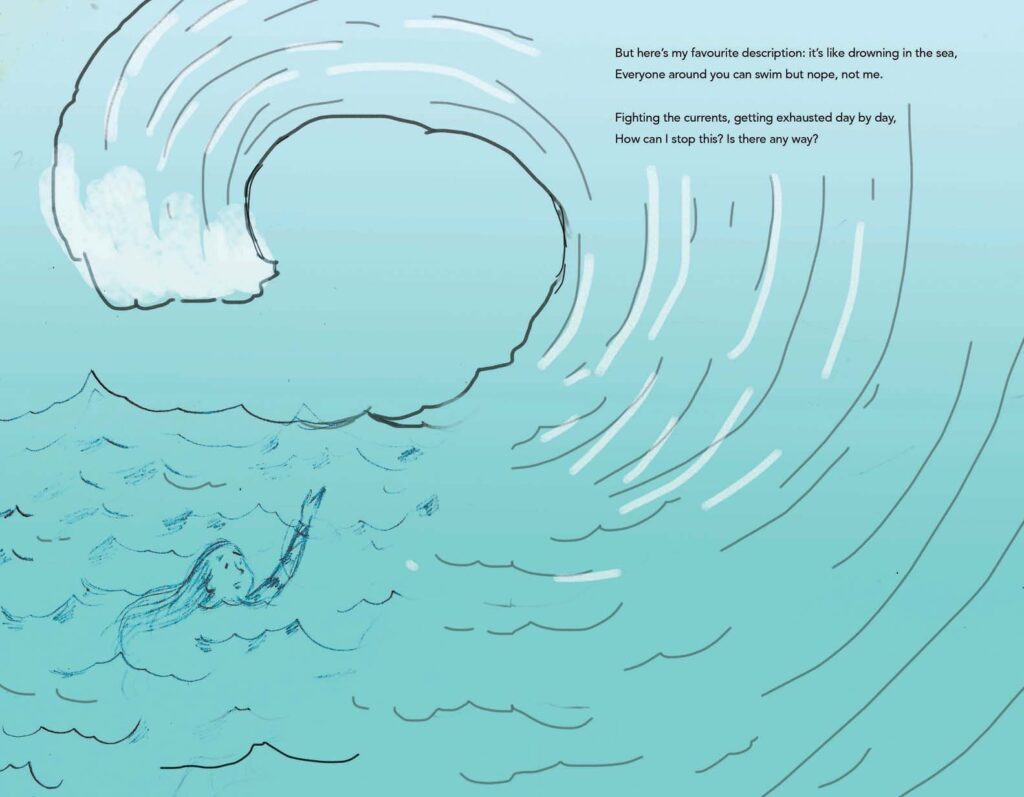

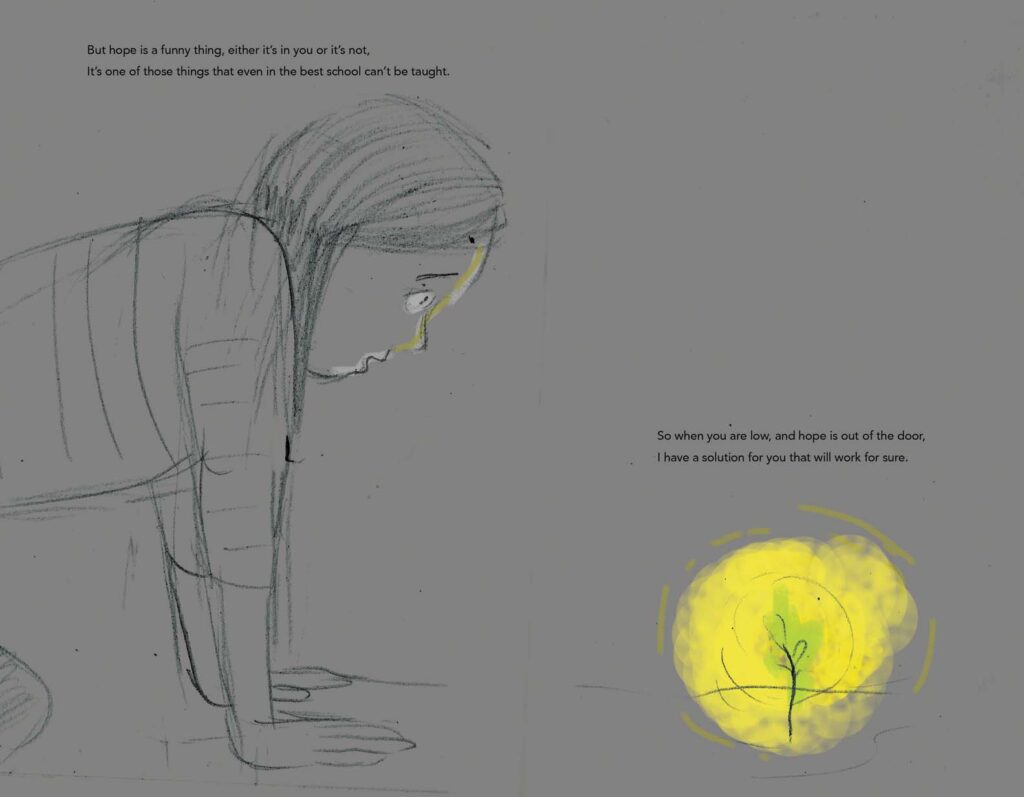

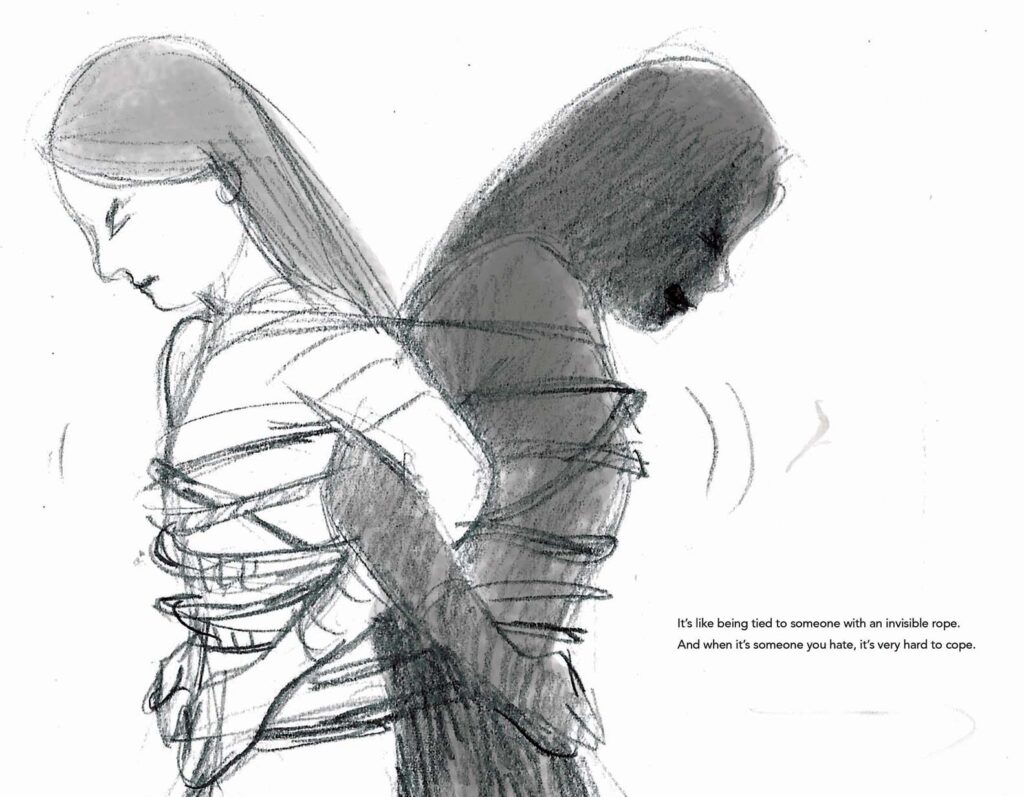

Priya Kuriyan’s illustrations for the text are out of this world. They complement the text well but also provide a narrative of their own to pull the reader in. While the drawings illustrate the text as beautifully and precisely as would be seen in a children’s picture book, the sophistication of the artwork is in keeping with some of the best international artists. Her eye for detail is astonishing. Her work as an illustrator begins from the cover, includes the endpapers and then the main text. To open the book and see the black endpaper that transforms brilliantly into a bright yellow at the end of the book is just one tiny detail that makes this book an extraordinary triumph. I had questions buzzing in my head for Priya while reading the book, so here is a lightly edited version of the interview conducted over email.

Priya Kuriyan is a children’s book writer-illustrator, comics maker and chronic doodler. She has directed educational films for the Sesame street show (India) and the Children’s Film Society of India (CFSI) and has illustrated numerous children’s books for various Indian publishers. She lives and works in the city of Bangalore and in her spare time makes funny caricatures of its residents.

- How did you approach this project? What was your initial reaction upon reading the text?

I first received the manuscript from the editor and went over it a couple of times trying to really get a sense of the genre. From the start, I was sure that though there are aspects of depression and mental health that are universal, (having had experiences with it myself and read up a fair bit) this was a very personal account of Kairavi’s experience with it. Therefore, I knew I would have to consult her at every stage of creating the book and that I wanted her voice to take centre stage. She had used metaphors in her poetry that I realised could translate very well into strong and evocative visuals that lead you into the mind of someone who is suffering so I knew that these strong full page illustration spreads would do justice to the text.

I had sent a few images from the early pages as samples to Kairavi and though she liked them a lot, she did rightfully ask me also to keep in mind that ultimately the book was also about hope.

2. How long did this project take to complete?

The manuscript was sent to me sometime in July last year and I had my first conversation with Kairavi in February this year over Skype. I worked on the project in bits and parts since then, but the serious work really started in April and was done by the end of June.

3. What was the initial concept note for the illustrations? Or did Kairavi and you have separate notes/ ideas that you then merged?

There was no initial concept note for the illustrations, but what I requested Kairavi after I had that first conversation with her was to pen down some words next to her lines as to what she saw when she wrote those words; not for every line, but at least for a few. Those did give me some cues that I could expand on. I would then send Kairavi rough drawings of my interpretations of those lines and she would then write back to tell me if it complemented the feelings that she intended to convey through her poetry

4. Your artwork is synonymous with light, freshness, primary colours etc. So how challenging was it to work with such dark colours, panel after panel?

Well, I think in my personal time where I don’t have to work on a client project, I do experiment with other kinds of media and genres. So, I didn’t really find the colour palette a challenge. I think most people have seen the work that I have done in the children’s book space (which I really enjoy being in), and then, one continues to get assigned work of the same kind based on what you’ve done before. I like and enjoy breaking away from my typical style from time to time.

5. Do you illustrate on the computer or do you use other mediums and then transfer the scans to the computer?

Most of the time I work analog first – scan my artworks, do some touch ups on an appropriate software and send digital files to the publisher. In this case I used dry pastels and charcoal for my original artworks.

6. If you had to write a note about creating the artwork for this story, what would you write?

That the illustrations should immerse you into a journey of a person trapped within their own mind, who is reintroduced to the idea of hope and ultimately releases himself/herself.

7. With this particular book, I feel that you have broken many of your creative boundaries and pushed yourself in a space that is new. I do not mean in that you are an over-reacher but as someone who has leapt into a new phase of creativity. Do you think this project changed you in any way? If so, what?

Hmm..It’s definitely a genre that I had not worked on before in the children’s book category. A lot of the work I do for adults (comics/ book covers etc) has tended to fall into a more serious (in the literal sense of the word) way. So, I’m not certain at the moment whether this has changed my work in a dramatic way. I think what I do with the next couple of projects that come my way will be what answers that question.

8. Which of these illustrations is your “favourite” of the book? Which of these illustrations has developed the furthest from the initial sketch? And why?

I think the one where the girl is tied to this black figure. I like the metaphor or the paradox of trying to release yourself from the person that you don’t know or recognise and yet knowing that person is you. I think that line really spoke to me. The illustrations that changed the most from the initial drawings were perhaps some of the earlier spreads. I think they were much darker and I later realised that the darkness must creep in gradually just as the light creeps in gradually into the latter part of the book.

9. What do you think is the relationship between illustrations and text? How does it vary depending upon the type of book it is — picture book, illustrated storybook, illustrations accompanying a story, chapter book, comics/graphic novels, novels etc.

The word and the text are entwined twins. I think in the case of picture books an illustrator anchors oneself on the text and is an equal partner when it comes to telling the story along with the writer. How long the rope needs to be, is the critical decision that the illustrator takes. It does vary vastly depending on each type of book. As far as possible, the illustrations that accompany any kind of format, should ideally not be a direct representation of what is in the text. It can bring further context to the story by adding more details that are not necessarily present in the text. In the case of comics, one has to also keep in mind that the page is being viewed panel by panel and also as a whole. So, text and image is intertwined differently out there.

10. What do you think are the fundamental guidelines an author should keep in mind while creating a concept note for an illustrator?

A clear idea of the context within which the book is set. Who the book is aimed at. Any image references that are essential to the research or details of the book. Having said that, it is always best if the author is generous enough or trusting enough to let the illustrator bring in his or her own voice to the book.

11. When did you discover your love for illustrations? What is your favourite medium for creating art? What is the medium you prefer to use while illustrating texts?

I love exploring different mediums and changing them depending on the book I’m working on. Needless to say stationary stores are the only stores I enjoy being in apart from bookstores.

I used to love drawing as a kid and also story books. I ultimately ended up studying animation in design school and as part of the course, we had illustration as a module. I really enjoyed it and perhaps that was when I considered that this could perhaps be something I could take up later. It was however a something I imagined I’d be doing on the side. I think I started taking children’s books seriously only after my 3rd or 4th book was published. There are no colleges that teach Illustration specifically in India and I think there’s a bit of a lacunae there since a lot of illustrators just by instinctively finding their way into a career in Illustration.

I don’t think I have a favourite medium as such. Though I work with watercolours quite a bit. I choose mediums depending on the nature/genre of the book. And I like exploring different techniques. At the moment, I’m inclined to say that graphite pencils are my favourite, but that might change in a few months from now.

12. Who are your favourite illustrators and who has influenced you the most

My favourite illustrators are Shaun Tan, David Weisner, Emily Gravett, Atanu Roy, Oliver Jeffers, Jon Klassen, Mickey Patel. All the illustrators of Target magazine that had a huge influence in my childhood namely Atanu Roy, Jayanto Banerji, Sudhaswatta Basu, and Ajit Ninan.

7 Oct 2020