A pile of books read — 4 April 2022

In recent days and weeks, I have read a pile of books but not had the time to write individual posts. So, perhaps it is best to create a combined blog post.

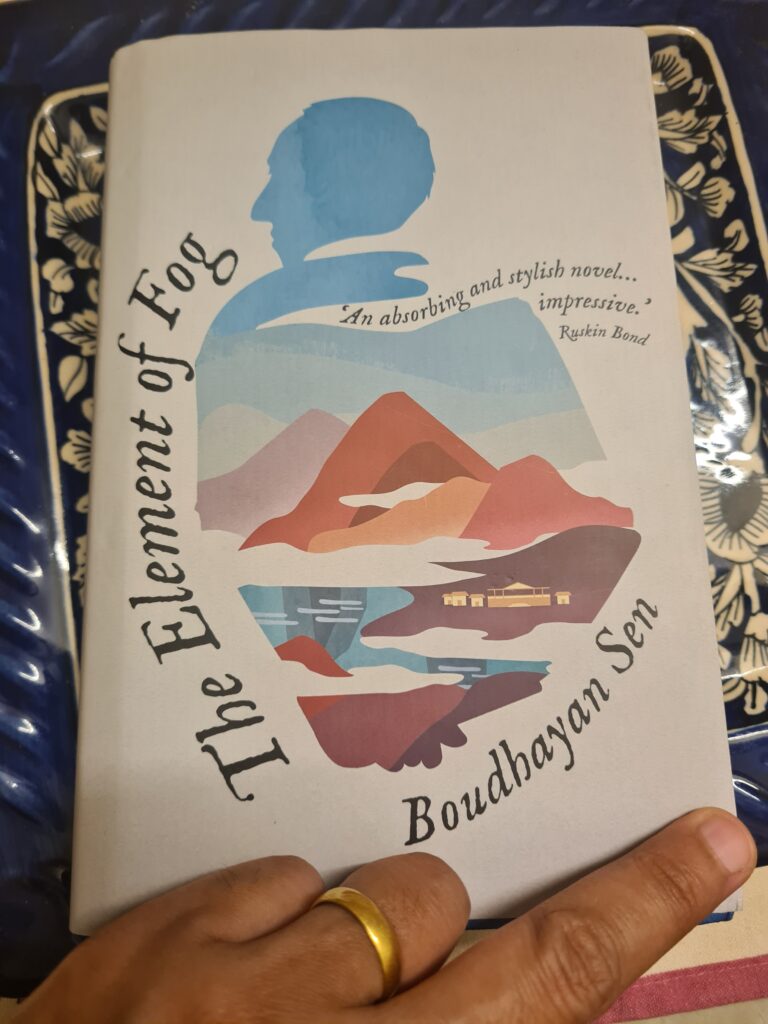

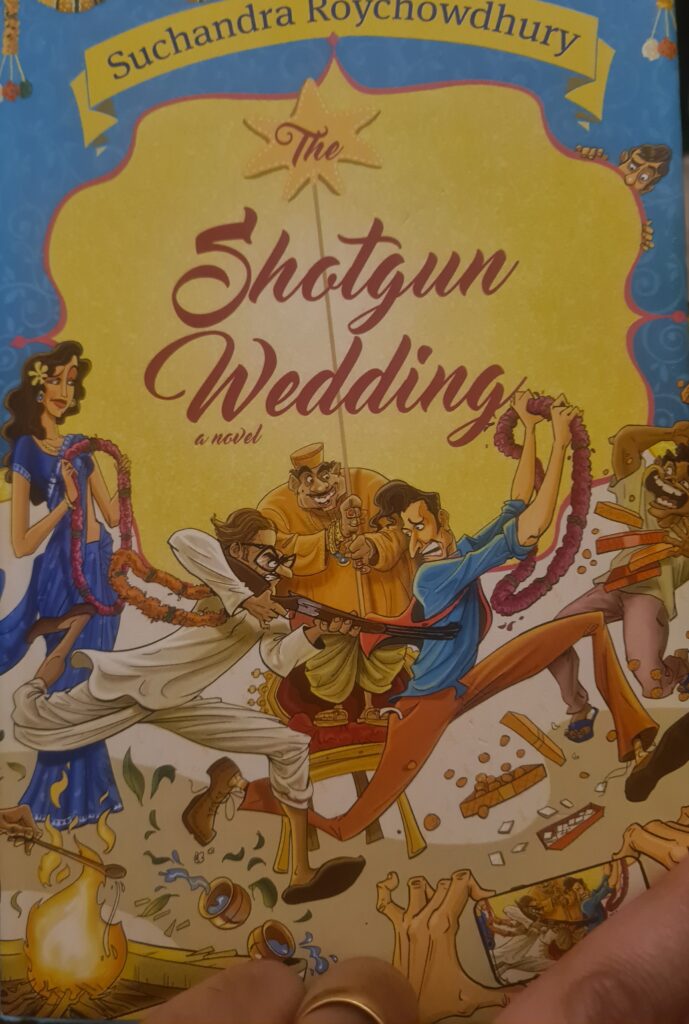

The two debut novels that I read were poles apart in tone and pace. The first debut novel is The Elements of Fog by Boudhayan Sen ( Juggernaut Books) is an unexpected pleasant surprise. It is a combination of old-fashioned ( read nineteenth century) novel and a twenty-first century contemporary fiction. It is a reflection of the plot too that is set apart in time by a century and a half. The common factor being that the story is set in a high school/boarding school that was set up in a hill station near Madurai. It is a love story that is very well told. Perhaps Boudhayan Sen will follow it up with another novel/ a collection of short stories that is equally well paced. The second debut novel is The Shotgun Wedding by Suchandra Roychowdhury ( Aleph Book Company) that is a fast-paced, comic, romance novel. It is more in the ilk of commercial fiction, noisy with chattering dialogue propelling the plot, easily read; with the potential of spawniing back stories,and perhaps Malgudi Days-like stories. Who knows?! Time will tell.

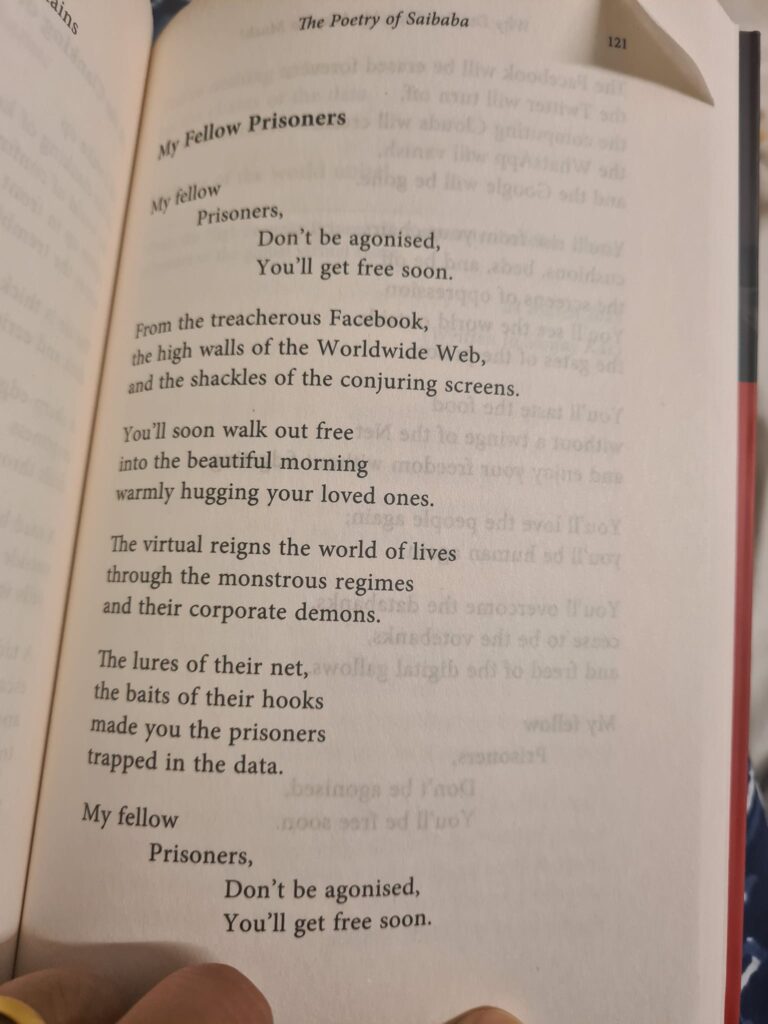

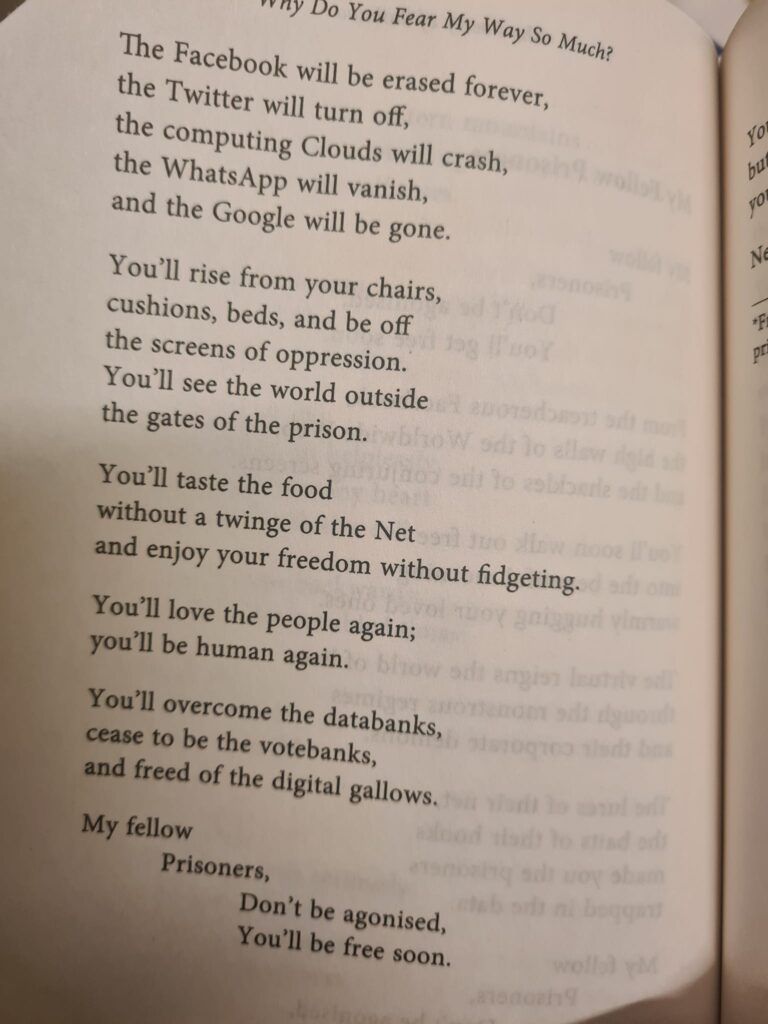

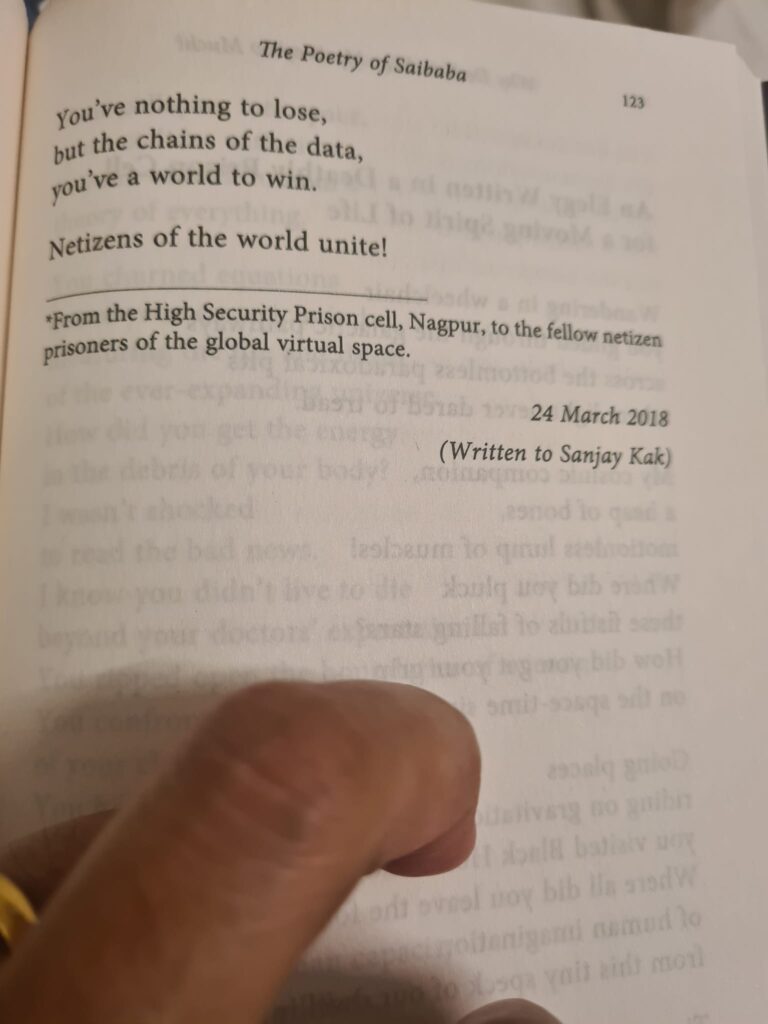

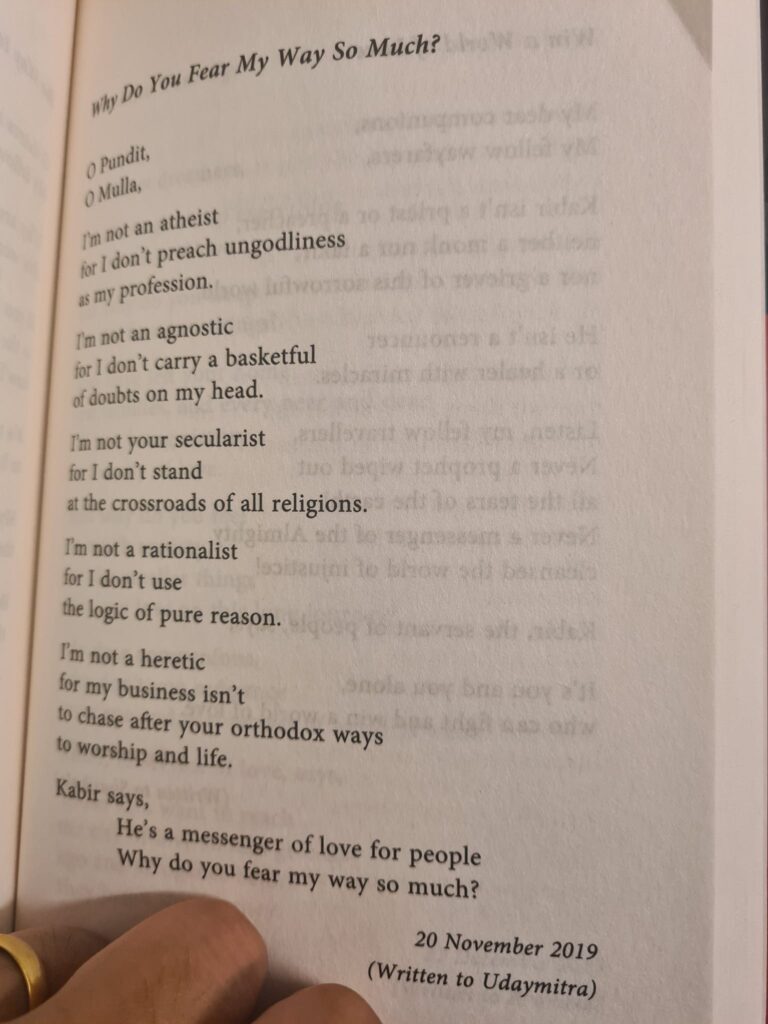

The two collections of prose and poetry are also very diverse. Why do you fear my way so much? : Poems and Letters from Prison by G. N. Saibaba ( Speaking Tiger Books) is very powerful. Most of the poems were written in the form of letters to his wife to avoid censoring by the prison authorities. Saibaba is an academic and an activist who is confined to a wheelchair and has been incarcerated since 2014. In 2017, he was sentenced to life imprisonment for his links to a banned organisation, CPI-Maoist.

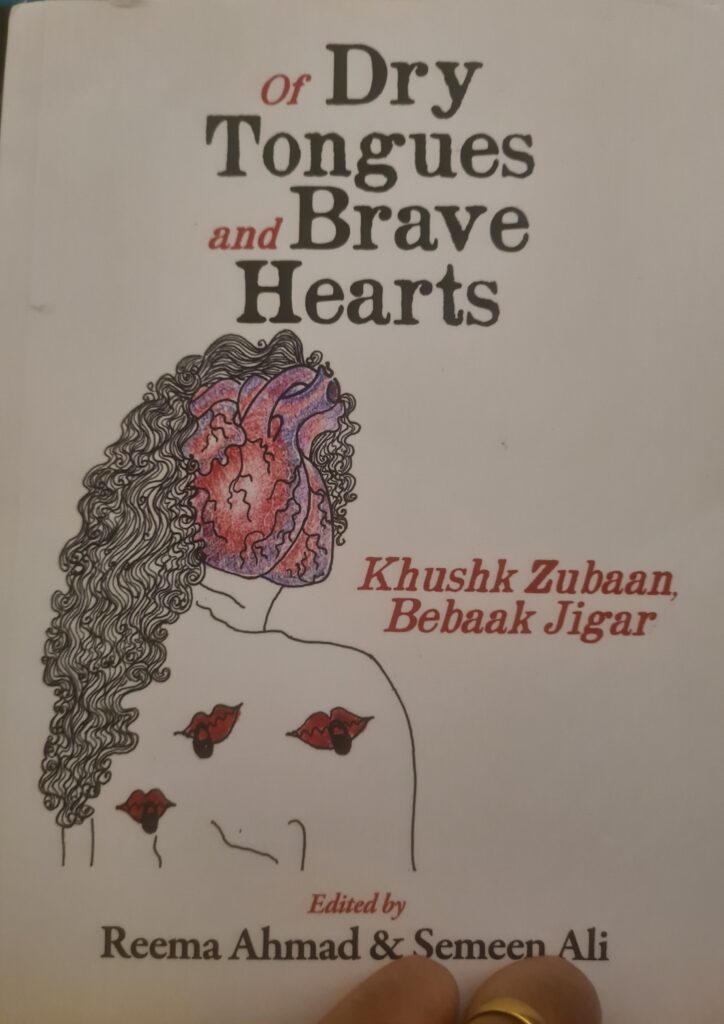

The second is an anthology Khushk Zubaan, Bebaak Jigar: Of Dry Tongues and Brave Hearts that has been edited by Reema Ahmad and Semeen Ali (published by Red River). It consists of poetry, fiction, non-fiction, and artworks. Red River publications go from strength to strength. This particular anthology when it was first published had a limited print run as the publisher, Dibyajyoti Sarma, was unsure whether it would sell. It sold so fast that a second print run had to be done within a month. The publications in this frontlist are experimental, grungy, and generous as many voices — established and new — are offered a platform with equal grace and respect. Of Dry Tongues and Brave Hearts is no different. It explores the theme of “ghar-bahir” or “in the home and outside”. All the contributors are women even though it may not be clear from the bios published in the book. Because the editors did not want to foreground gender, instead the focus is on the individual identities, the myriad voices. This book is meant for everyone. Do read it.

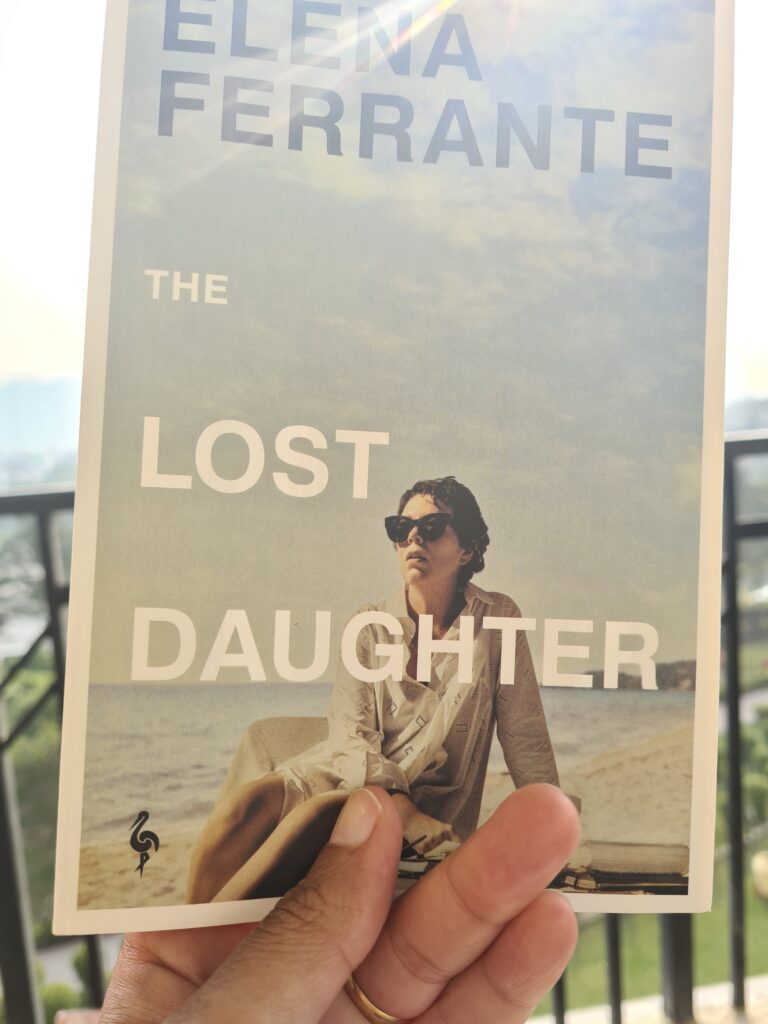

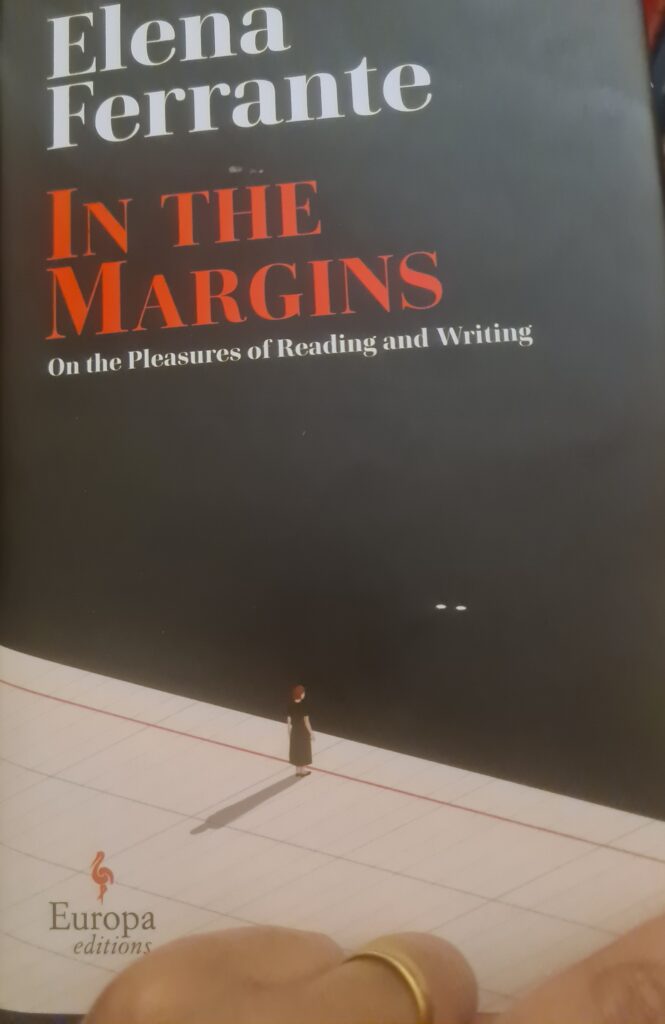

Perhaps at this point, it may be appropriate to mention Elena Ferrante’s new book, In the Margins: On the Pleasures of Reading and Writing, translated from the Italian by Ann Goldstein and published by Europa Editions. The four essays included in this book are the Eco Lectures that the author wrote. In November 2021, the actress Manuela Mandracchia, in the guise of Elena Ferrante, presented the lectures at the Teatro Arena del Sole in Bologna, together with ERT, Emilia Romagna Teatro. There are many pearls of wisdom that Ferrante shares with regard to close reading of texts, her own writing craft and experience of reading some of her favourite writers such as Dante, Emily Dickinson, Gertrude Stein, Ingebord Bachmann, and others. There are many portions in my copy of the book that I have underlined heavily. There is a particular section that is worth sharing:

…in order to devote ourselves to literary work must we subscribe to the great scroll of writing? Yes. Writing inevitably has to reckong with other writing, and it’s from the terrain of the already written that the sentence might jump out that sets in motion a small admirable book or the great book that displays a trajectory and constructs a unique world of words, characters, and conflicts.

If that’s true for the male “I” who writes, it’s even more so for the female. A woman who wants to write has unavoidably to deal not only with the entire literary patrimony she’s been brought up on and in virtue of which she wants to and can express herself but with the fact that that patrimony is essentially male and by its nature doesn’t provide true female sentences. Since I was six my “I” brought up on male writing also has had to incorporate a kind of writing by women for women that belonged to it, was appropriate to it — writing in itself minor precisely because it was barely known by men, and considered by them something for women, that is, inessential. I’ve known in my life very cultured men who not only had not read Elsa Morante or Natalia Ginzburg or Anna Maria Ortese but had never read Jane Austen, the Bronte sisters, Virginia Woolf. And I myself, as a girl, wished to avoid as far as possible writing by women: I felt I had different ambitions.

(p. 76-78)

Suddenly, the title is illuminating. It is not merely about being a professional writer preoccupied with the craft of writing but metaphorically, it is about being a woman and a writer. It is incredible how the same stuff has been said over and over again and yet, it seems new. Read the book.

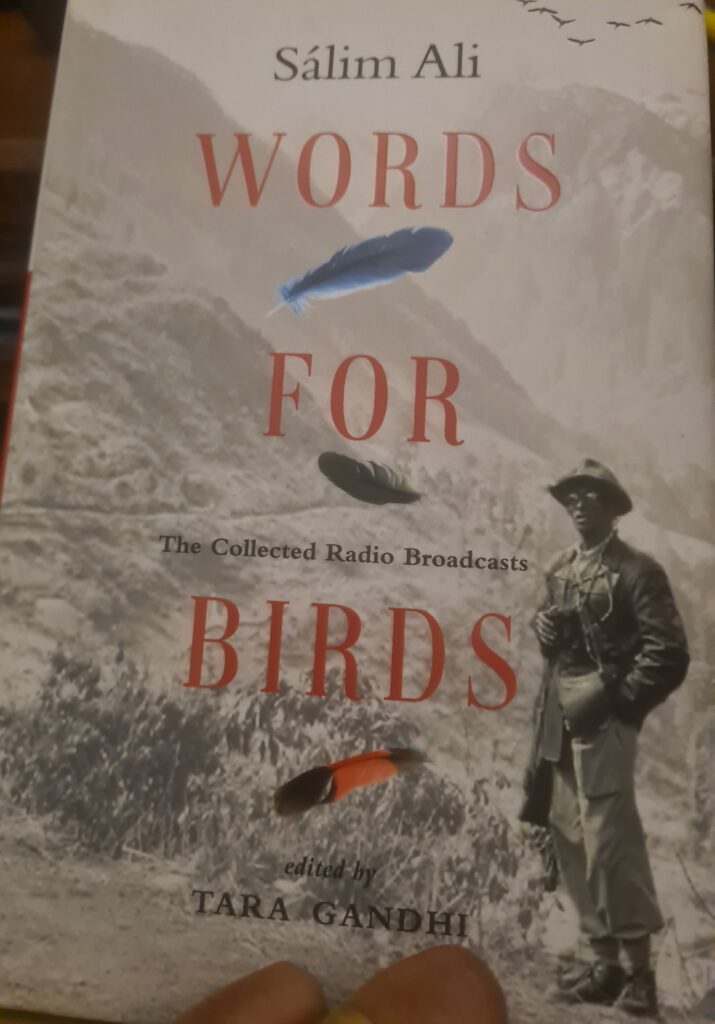

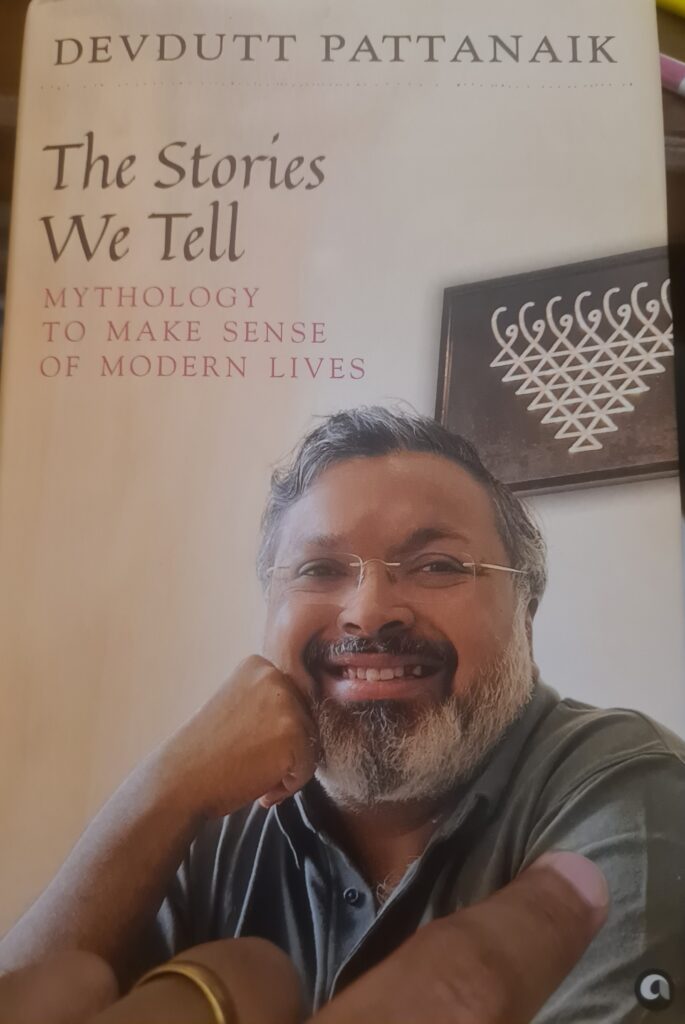

The idea of writing and what it takes to write are eternal questions. In the new age of publishing, “content” works in multiple ways. No longer is it necessary to first publish a book before exploring other platforms. The next two books belong to this category. Both are publications stemming from talks delivered over the radio and short stories shared on YouTube. The first is by well-known ornithologist, Dr Salim Ali called Words for Birds. It is a collection of radio broadcasts that have been edited by Tara Gandhi. It has been published by Black Kite (an imprint of Permanent Black) in collaboration with Ashoka University and distributed by Hachette India. These broadcasts are from 1941 to 1980 with the bulk being spanning 1950s-60s. It is an interesting exercise reading the essays as there is a gentle pace to them, much as one would hear over the radio, enunciate slowly and clearly to be heard. The idea being to communicate. The second one is The Stories We Tell by noted mythologist Devdutt Pattanaik ( published by Aleph Book Company). It consists of short stories that originated in a webcast that Pattanaik began from 21 March to 31 May 2020. It was in the early days of India’s countrywide lockdown to combat Covid-19. He says:

People were terrified of the virus and I wanted to life their spirits by telling them stories from our mythology that would make them less anxious. At these stories were told from 4pm to 5pm, around teatime, I named my webcast “Teatime Tales”. I genuinely believed the lockdown would end in a few weeks, but it became clear that we would remain indoors for a long time. I knew I would not be able to sustaing the enterprise endlessly. So, I decided to end it gracefully after seventy-two episodes. [ Seventy-two being an important number across cultures. He elaborates upon it beautifully in the book.]

These are very short, short stories. Very easily read. The sentences are short. The ideas develop slowly and methodically. There is no cluttering. The conversion of the oral into print has been done very well. The stories retain their capacity to be read out aloud. Also, as with many age-old stories and folklore, these stories narrated by Pattanaik lend themselves to be expanded and embellished. In his introduction, he provides a general description as “our mythology” and since his name is synonymous with mostly retelling of the Hindu epics, many readers would probably expect more of the same. Extraordinarily enough, Pattanaik displays extensive knowledge and understanding of other faiths too. Slim book, easily shared and presented.

Ultimately, it is the Internet that has made the revival and dissemination of literature possible. Earlier, a few copies were printed and circulated. But now, there is mass distribution of books and content — whether legitimately or pirated versions is not the point right now. The fact is literature is available to many, many people. Physical and ebooks can be bought online. Payments are made. Today, we take digital payments for granted but there was a time, in the not too distant past, that this concept did not even exist. In the 1990s, people were experimenting with the idea but it was not taken too seriously. Then, came along a bunch of youngsters, from 19 to their early 20s, who felt that this was worth investigating. The Founders by Jimmy Soni is about these young men such as Max Levichin, Reed Hastings, Elon Musk and Peter Thiel. It is a book that is full of details regarding the fintech startup, surving the dot com bubble and its ultimate sale to eBay for US$1.5 billion — at a time when such figures were unheard of and certainly not for technology. This story is told at a furious pace, it is intoxicating reading about the highs and lows of the founders, but it is also seeped in masculinity. It confirms the belief that professionalism is a philosophy that is acceptable when imbued with patriarchy and makes no allowances for women and other responsibilities of life. It is almost as if one has to be wedded to the job and even in a marriage there is more leeway than these startups provide. On a separate note, I had emailed Jimmy Soni a bunch of questions for an interview on my blog. He had agreed in principle but then chose not to acknowledge the email, later asked the person who had set up the interview if he could change my questions, then suggested that one of the questions was incorrect but would not say which one and ultimately, he refused to do the interview. Here are the questions. Despite this unfortunate glitch, I would recommend The Founders.

Finally, an integral feature of the Internet is the search option. It is a critical part of the world wide web. It enables information to be discovered and shared. This is done by searching a vast index that the search engines maintain. It is nothing more basic than that — a feature that has been a significant part of the codex for more than 800 years, is now a fundamental feature of the Internet. So despite technological advancements being made, certain characteristics remain and continue to be adopted and adapted to new frameworks. Read more about it in this incredibly fascinating account by Dennis Duncan in Index, A History of the . I loved this book!

A vast and eclectic selection of books to choose from!

4 April 2022