I interviewed legendary German writer of fantasy fiction for children Cornelia Funke. Scroll published the interview on 2 December 2018. It is c&p below too.

I interviewed legendary German writer of fantasy fiction for children Cornelia Funke. Scroll published the interview on 2 December 2018. It is c&p below too.

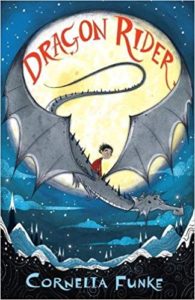

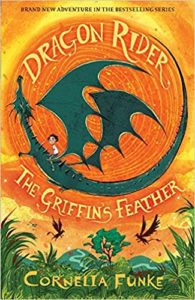

Award-winning German writer Cornelia Funke, whose books for children have sold millions of copies worldwide in several languages, released The Griffin’s Feather – the sequel to her immensely popular Dragon Rider after a gap of 16 years. The novel, whose animated version is in the works, is about young Ben and his silver dragon Firedrake who go on a magical quest in search of the Rim of Heaven, a quiet and safe haven where dragons may live in peace without being disturbed by human beings.

The Griffin’s Feather marks the return of Firedrake, Ben and his adopted family – the  Greenblooms. They all live in MIMAMEIDR, Norway, where accommodation may be found for fabulous guests such as trolls, impets, fossegrims, mermaids, dragons and winged horses, since they would pass unnoticed more easily in the country’s remote forests.

Greenblooms. They all live in MIMAMEIDR, Norway, where accommodation may be found for fabulous guests such as trolls, impets, fossegrims, mermaids, dragons and winged horses, since they would pass unnoticed more easily in the country’s remote forests.

The quest is for a “Griffin’s Feather”, which can be swiped over the three eggs of the winged horses so that their children can either be born or face extinction. Unfortunately, their mother has been killed. So it falls upon Ben and Firedrake to ensure their survival, but not before many incredible adventures along the way. The reading experience is made all the more remarkable with the incredible illustrations accompanying the text.

Funke spoke to Scroll.in over email to talk about her new book and her methods of working, accompanying her answers with this note: “India has a very special place in my heart and I feel so honoured by how passionately my stories are welcomed there. Please give my love to India!” Excerpts from the interview:

How did these magical landscapes of Rim of Heaven, MIMAMEIDR, temple of Garuda and Pulau Bulu come to be?

There is often the misunderstanding that fantasy is about other worlds. I don’t believe that. My stories are always a love song for this world and all the landscapes you travel in them are inspired by places and landscapes of this planet. When I sent the dragons to the Himalayas I did that because I thought it believable that dragons can hide between its mountains.

It’s much harder to find such a refuge in Europe, but the woods of Norway felt like a believable home for MIMAMEIDR and a refuge for fabulous creatures. The temple of Garuda speaks of course of my love of India! And Pulau Bulu…where else would Griffins be able to hide but on one of the countless islands of Indonesia? A boy from Indonesia, Winston Sevala, who visits my website regularly, helped me with research and names so I made him a dragon rider to show my gratitude.

To say one more thing about the Rim of Heaven: I bought 10 acres of land in the Santa Monica Mountains to keep them wild and to one day bring young artists from the countries I am published in to this magical place and see what the wilderness inspires in them. I promise that of course at least one will come from India!

When Anthea Bell (who also translated, among others, the Asterix comics) was translating the books, how involved were you with the process? Did you compare the German and English texts? Are these in any way different?

Of course every language has its very own voice, even with as brilliant a translator as Anthea. At a panel in Jaipur I learned about the impossibility of transferring the lushness of Hindi to an English translation. But Anthea tailored the English clothes for my stories so beautifully that sometimes I liked them even better than the German clothes. We worked very closely together, especially when it came to names and translating them, and Anthea’s research and intricate knowledge of almost everything always fascinated and enchanted me and made the translation process magic in itself.

Why is there a long gap between the two books in the series? Dragon Rider came in 2000 and Griffin’s Feather wasn’t published till 2016.

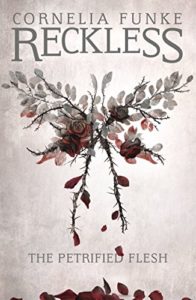

In Germany it was even longer! I tried several times to write a sequel to Dragon Rider, but each attempt felt repetitive and not as strong as the first adventure. Then I developed the iPad App for Reckless with Mirada and was so happy with the visual interpretation of my world that we began to work on something similar for Dragon Rider. While playing with stories and motives (I just released an audio play based on the work.) I once again fell in love with the characters and suddenly I saw so clearly how the story continues that The Griffin’s Feather almost wrote itself. The digital version had inspired the printed word!

Your stories about “fabulous creatures and other rare things” are imaginatively happy and joyful stories for children. What prompted you to write such stories?

I just write stories I love to read myself. And I am profoundly enchanted by children and young readers, by their openness and curiosity, by their will to still ask the big questions about the world: where do we come from? What is this all about? Why is the world so beautiful and terrible at the same time? Children also still understand that we are just part of a huge web and connected to every plant and creature on this planet. They are still shape shifters and go easily into a story, whereas adults often hesitate to allow their imagination to give them feathers and wings.

Your knowledge about fairies, folklore, myths and legends around the world is encyclopaedic as evident in these novels. How much research was required for writing these books?

Your knowledge about fairies, folklore, myths and legends around the world is encyclopaedic as evident in these novels. How much research was required for writing these books?

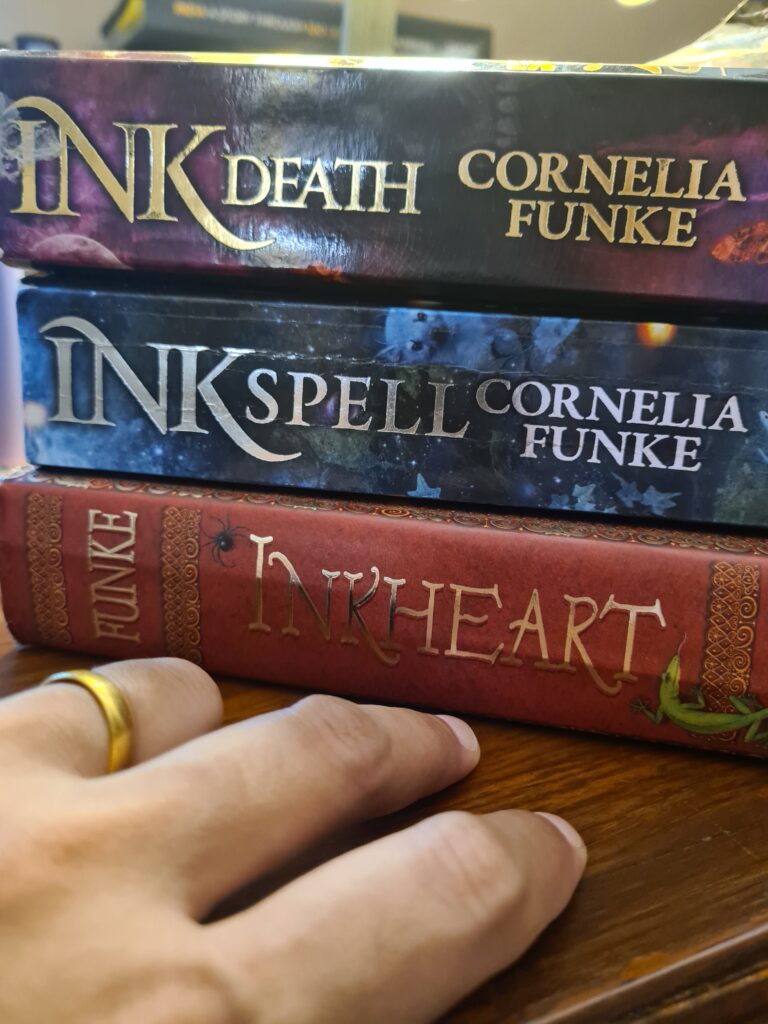

Not as much as for the Reckless books. That series actually taught me much about research and how to weave myth and the past into my stories. By now I use my research always on my three worlds: Mirrorworld, Inkworld (which is Mirrorworld 500 years earlier) and the world of Dragon Rider. They all inspire each other, which makes it easy to work on all three at the same time – which I love to do.

Given that you illustrate your own books, do you see the story as a combination of text and illustrations, or is it more of a case of the text being bolstered by the illustrations?

In the past few years illustration have become more and more important for my storytelling. It started when I began to write my stories by hand. I often added sketches, and for The Griffin’s Feather I drew all the characters first before describing them. I love that drawings often reveal aspects of a character that I would have missed by just describing them. For my new Reckless book, The Islands of the Fox, some of my characters even showed up on canvas while I was painting with oil colours, claiming a part in the story or making me realise that a character whom I thought to have human shape does indeed prefer to show himself as a Zentaur.

If you are particular about the layout of the printed text, how do you envision these stories will work in other formats such as digital, interactive apps, films, etc?

I am slightly disenchanted by the movies, as nine adaptations have proved how much is lost from page to screen. I guess my books might do better in a TV format, as they have so many layers and characters. My favourite adaptation by far is the Reckless App for iPad. It made all my dreams about a visual adaptation come true, and instead of shrinking my world, it grew it.

How did you select the opening quotes for each chapter in Griffin’s Feather? Is the lay-out of the page (opening quote, story, illustrations) as important as movement of plot and action in the story?

Choosing quotes is always quite a time-consuming process (and my publishers have a lot of work clearing the copyright), but I love to have other voices in my books. As for the layout – as a visual artist I do love of course to play with initials or chapter headings and this time I did more than 100 ink drawings.

The manner in which you play with figures of speech and minutely describe the magnificent landscapes and its creatures makes me wonder if after writing the manuscript you “test” the stories on younger readers by sending them pages or reading aloud to them.

No, I actually don’t. I only read aloud to myself – and I send the manuscript to my daughter Anna, who is 27 by now and my very best editor (and the strictest one). My son Ben prefers to be a character in my books.

The underlying themes in these books is conservation of the environment and its creatures. In fact you have chosen to immortalise Jacques Cousteau, David Attenborough and Jane Goodall – three of the giants of environmental conservation in the Twentieth Century. Why them?

Not to forget Sylvia Earle! Their passion for the non-human world is exemplary for me, but there are for sure many many more who deserve to be named.

What did you like to read in your childhood? Did you ever desire books like the ones you create?

I always loved fantasy and adventure stories, so yes, I guess I am writing what I looked for in the library as a girl.

3 December 2018