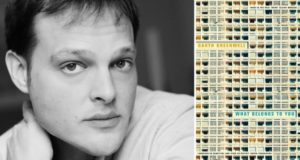

Garth Greenwell, “What Belongs to You”

…more and more I took refuge in books, not serious or significant books but books that offered an escape from myself, and it was these books, or rather our shared love for them, that bound me to the few friends I had…

…more and more I took refuge in books, not serious or significant books but books that offered an escape from myself, and it was these books, or rather our shared love for them, that bound me to the few friends I had…

Garth Greenwell’s debut novel What Belongs to You is about a nameless American schoolteacher who is based in Bulgaria. Funnily enough even though the narrator remains nameless the two cultural landscapes that influence him are very much fixed in a period —the Republican conservative homophobic Kansas and Bulgaria emerging from the Soviet era, detritus of which are still visible in the dilapidated buildings and in the attitude of the people. The novel is divided into three parts — Mitko, A Grave and Pox. In fact “Mitko” won the Miami University Press Novella Prize. What Belongs to You begins with the narrator looking to have sex and comes across Mitko in a public bathroom and from then on they forge a curious relationship. The second section is about the narrator receiving news about his father’s hospitalisation and the flood of memories it unleashes. The final section is about his mother’s arrival in Bulgaria and due to a concatenation of events primarily the fleeting return of Mitko in the narrator’s life, there is a sudden unyoking of himself from his past–immediate and childhood. It is an epiphany that liberates him paradoxically leaving him in despair too. It seems to happen subconsciously while recalling his experience of a severe earthquake.

…the first time I had known that absolute disorientation and helplessness, the first time I had felt in that incontrovertible way the minuteness of my will, so that underlying my fear, or coming just an instant after it, was total abandon, a feeling that wasn’t entirely unpleasant, a kind of weightlessness.

At Jaipur Literature Festival 2016, Colm Toibin said while researching for The Master, his novel/tribute on/to Henry James, he realised gay fiction was a 21st century phenomenon. He also observed that “fiction contains many mansions” a comment apt for Garth Greenwell’s debut novel. What Belongs to You is much more than a fine example of gay fiction with its extraordinarily bold voice; it is a Künstlerroman, a narrative about the artist’s growth to maturity. What Belongs to You is in the same category as James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man or even Alison Bechdel’s graphic memoir, Fun Home. It is evident in the experimentation of form in “A Grave” such as the long unbroken paragraphs sometimes running on for pages and pages that fit snugly with the literary device of interior monologue. The lyrical prose of “A Grave” is structured as magnificently as Isabel Archer’s reflection in Henry James’s Portrait of a Lady. In both novels the interior monologues by the central characters are pivotal not only to the structure of the plot but also to the radical transformation they wrought in the narrator and Isabel and to the chain of events to follow.

At one level What Belongs to You is reading a story about a young man living in a new land and yet it is also recognising what belongs to you are who you are, what you make yourself. This could be by rejection such as the narrator’s complicated relationship with his father or by accepting new influences as the narrator says by “thinking it half in Bulgarian and half in my own language, which I returned to as if stepping onto more solid ground.”

One of the best interviews published so far with Garth Greenwell has been with Paul McVeigh. “The world according to Garth Greenwell” (The Irish Times, 25 April 2016. http://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/the-world-according-to-garth-greenwell-1.2623753)

Garth Greenwell is a boldly confident youthful writer who writes extraordinarily beautiful prose with panache. Hopefully one day the following writers will be together on a panel discussing the art of blending truth and fiction, writing a memoir-novel: Damian Barr, Paul McVeigh, Sandip Roy, Roxane Gay, Garth Greenwell and Alison Bechdel.

What Belongs to You is a debut that will be talked about for a long time to come!

Garth Greenwell What Belongs To You Picador, an imprint of Pan Macmillan, London, 2016. Hb. pp. 196. Rs 550

18 May 2016