Aleph announces children’s literature list

30 March 2022

30 March 2022

This morning I finished recording a panel discussion on “Children’s literature in India” at All India Radio, the national radio channel. After the fabulously animated session was over, the producer informed us about the magnificent history of the table that we were recording at.

This table is where the first prime minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, made his “Tryst of Destiny” speech.

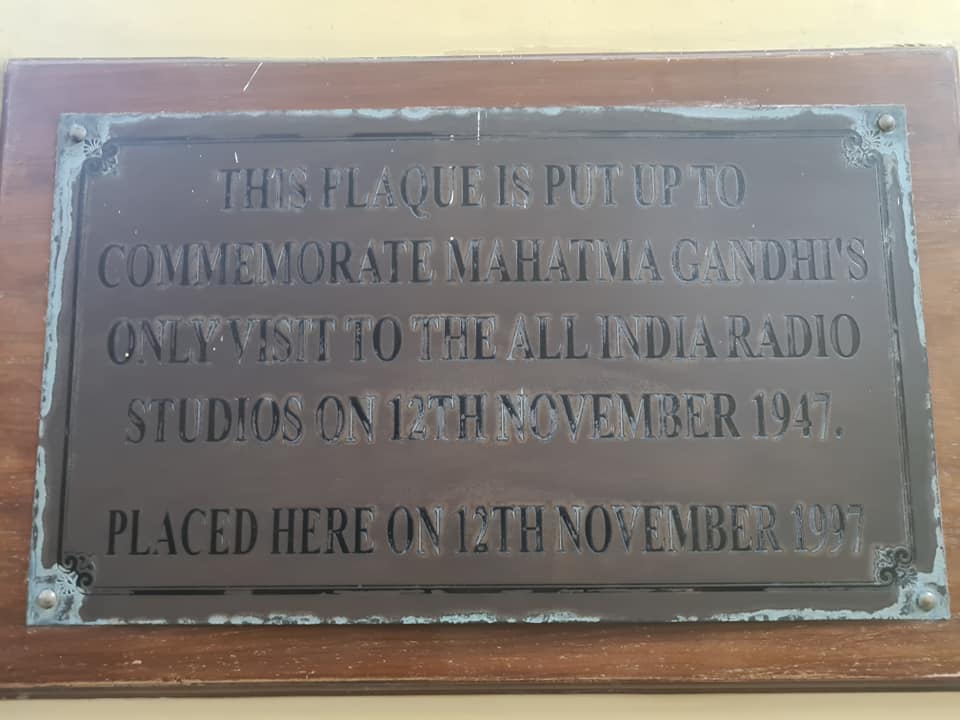

This table is where Mahatma Gandhi appealed to the nation to stop rioting. It was the one and only time that he visited the AIR studios — 12 Nov 1947.

This table is where Emergency was declared.

All India Radio has ensured that it is preserved and used. In all these decades they have never changed the bar from which the microphones hang.

Needless to say, all of us had goosebumps, by the time the producer finished his story.

Perhaps the producer was so pleased with the outcome of the recording. He really liked it. Truly, I am glad he did not tell us earlier. The moment he did, all of us jumped out of our seats. It just seemed surreal to be at the same desk where so many defining moments of our country’s history had played out. Apparently, most of the AIR employees are told this when they are training for their posts. But most do not share it with their guests as they are usually in a tearing hurry to leave after the recording.

Or

Perhaps it has something to do with the nature of our conversation where I shared a lot of our publishing history with reference to children’s literature. Made a point to connect it with developments in modern India. Maybe the producer was responding to the histories we were sharing? I do not know. It just happened so spontaneously.

I have no idea why were singled out for this precious piece of news. But this is a privilege indeed to be at the same table that has witnessed so much of modern Indian history.

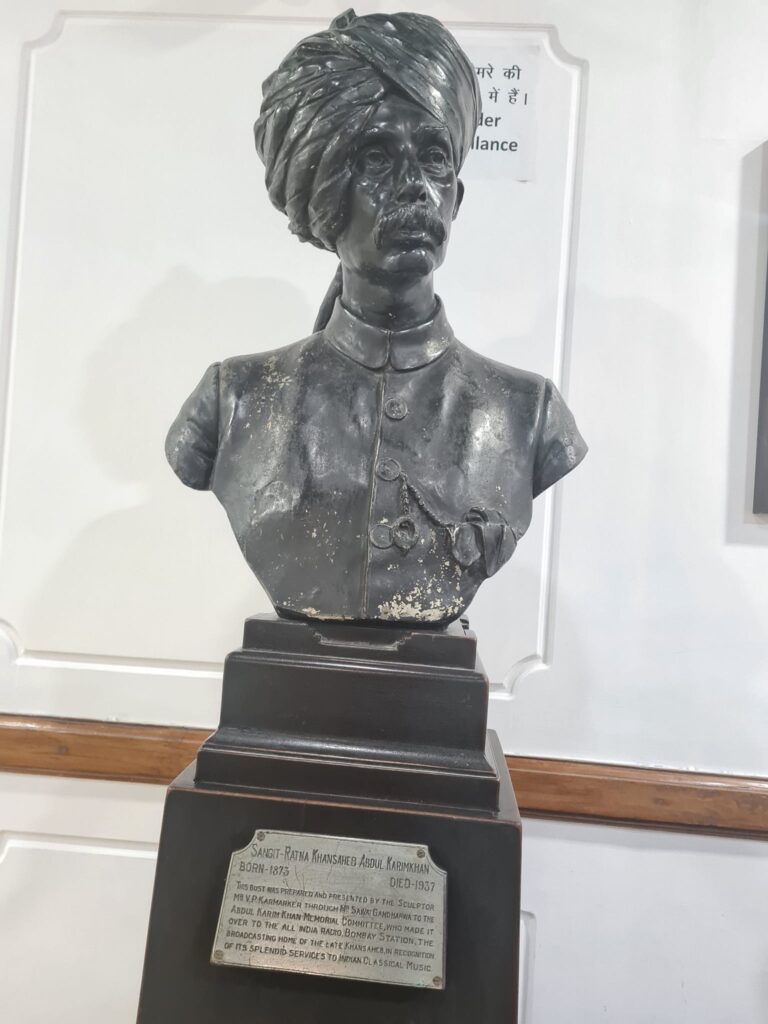

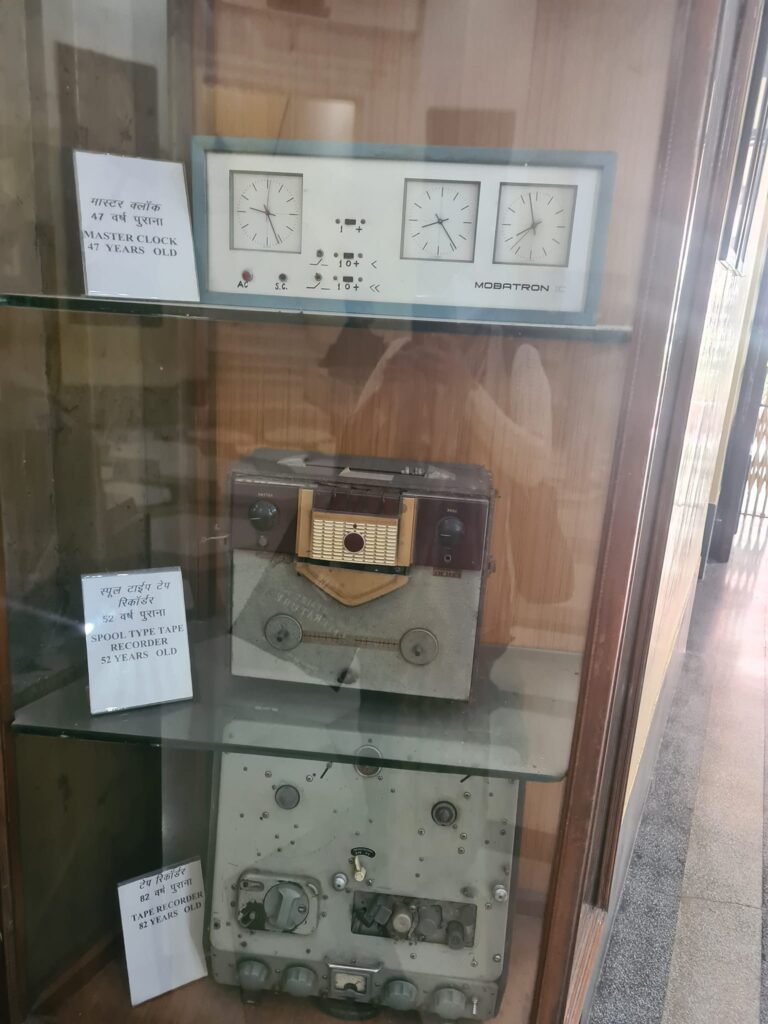

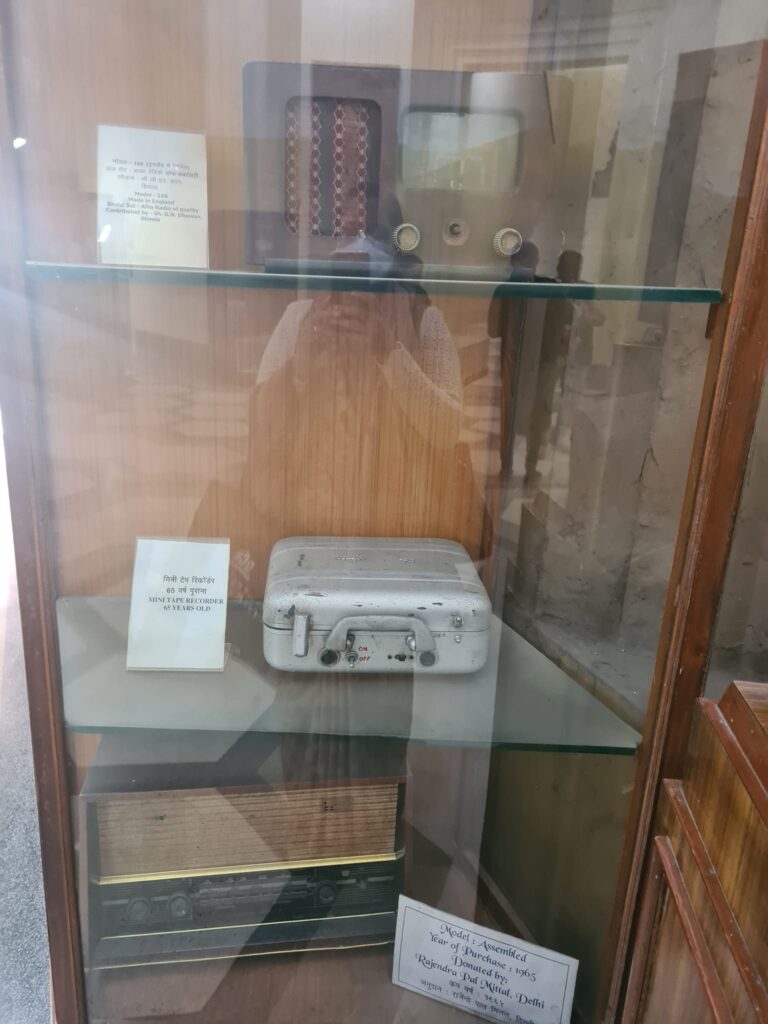

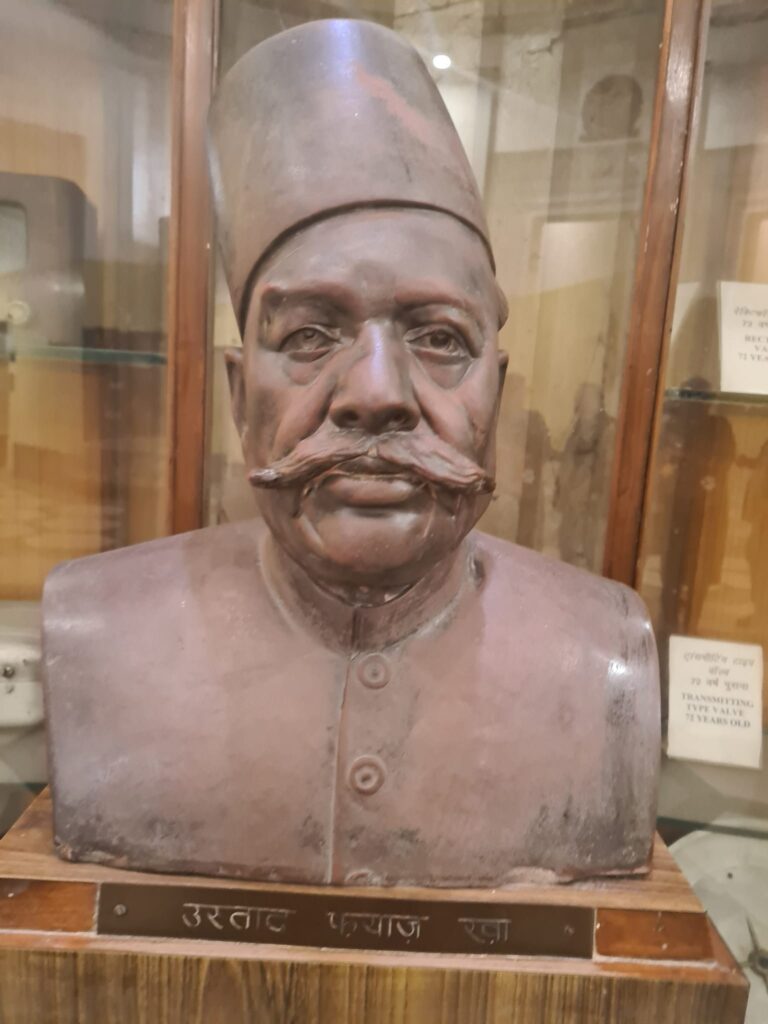

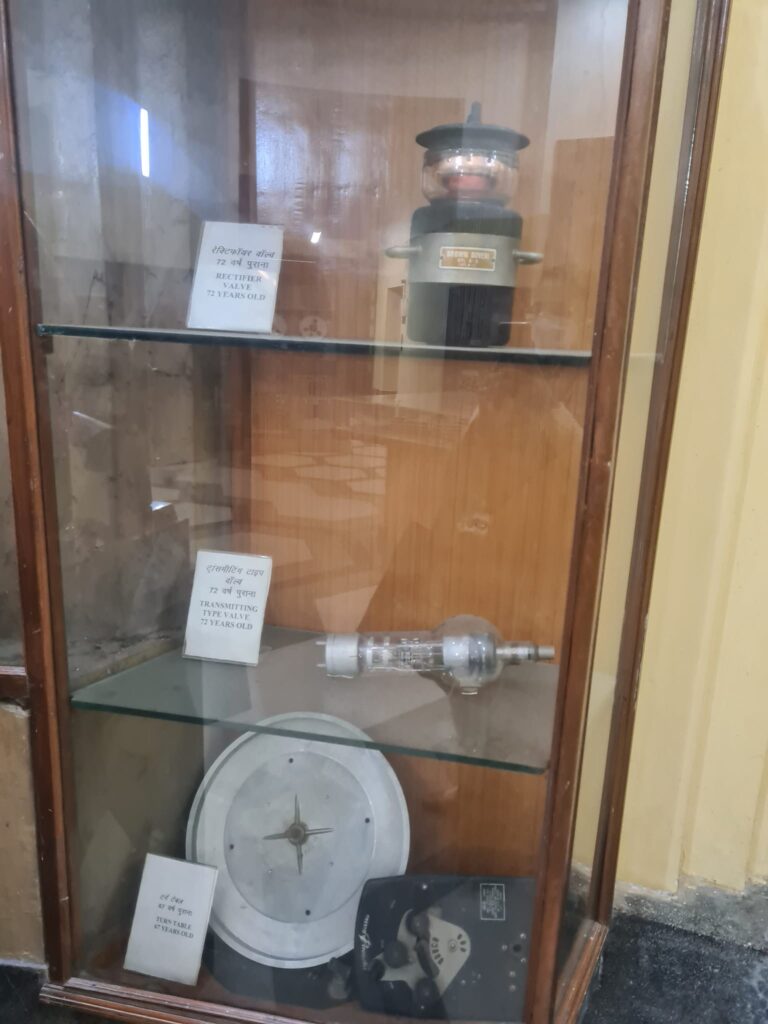

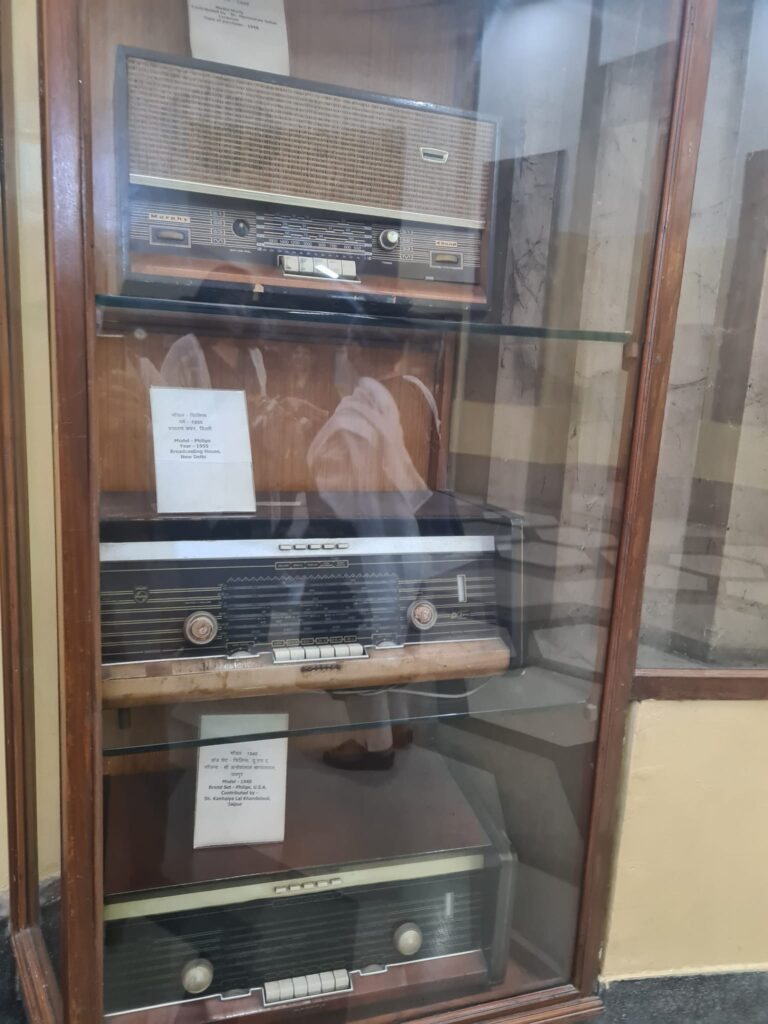

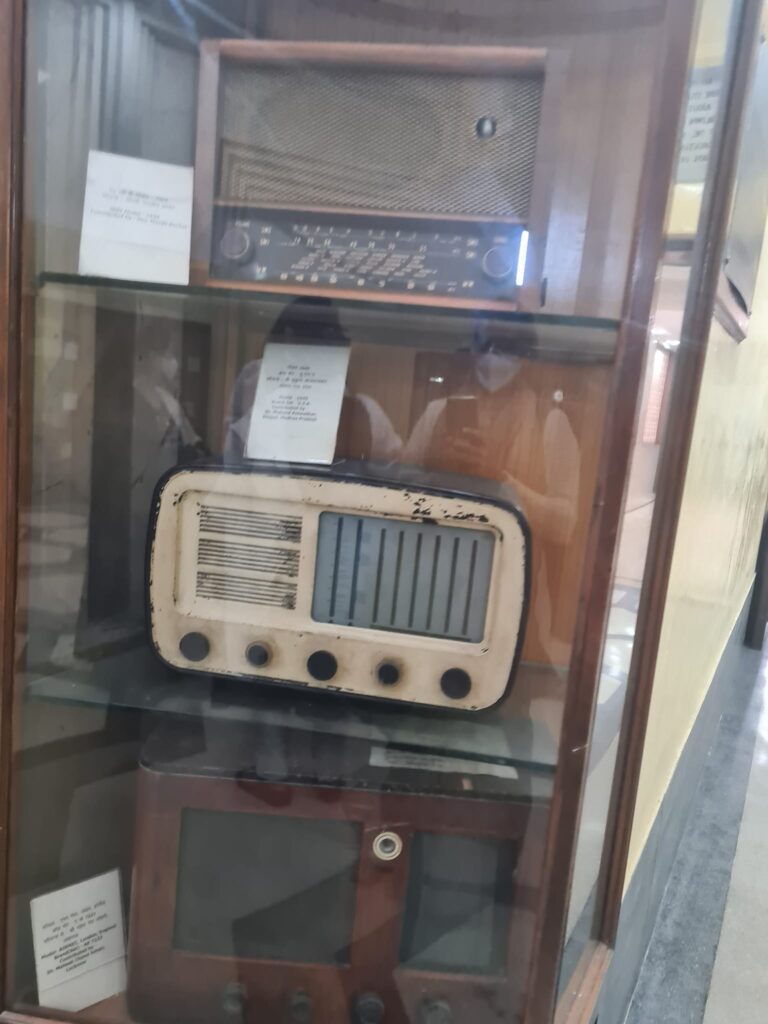

Below are photographs of display cabinets in the foyer of AIR showcasing sound recording equipment.

25 Nov 2021

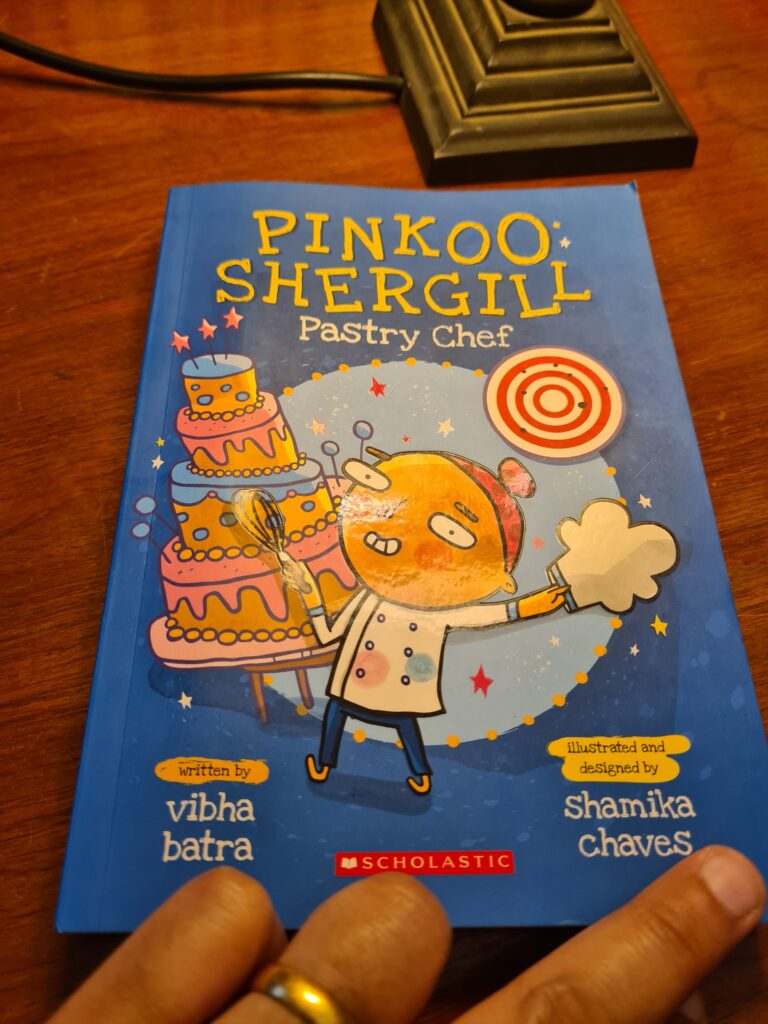

This book is utterly perfect! In terms of story, plot, pacing and literary craftsmanship. It makes one chuckle with delight as the antics are so believable. The manner in which Vibha Batra has inhabited a child’s world is very well done.

Ten-year-old Prabhjot Shergill aka Pinkoo adores baking. He dreams of making Olympic history by winning the gold medal at the Bake-a-Thon event. Instead he has to settle for sneaking into the kitchen to bake exquisite creations while the adults are preoccupied with other stuff. Sometimes it is at the cost of skipping his shooting classes that his father insists upon. Pinkoo is not interested in living out the dreams of his late grandfather or father as a shooter, instead he prefers to be a world class baker.

Aided and abetted by his best friend Manu and his pestilential little cousin, Tutu, the kids hatch a plan of getting Pinkoo to participate in the international programme, “The Great Junior Bake-a-Thon”. The competition is slated for an Indian edition, to be recorded in Chandigarh and finals in Mumbai. They are assisted by their classmate Nimrat, who they don’t particularly like, but her father runs the best coffee shop in Patiala, offering the best confectionary for many miles around. Nimrat persuades an ex-baker of her father’s, Chef Khanna, to train Pinkoo. The only reason that Nimrat assists Pinkoo is that she overheard him being taunted in the school canteen by the school bullies for wanting to become a pastry chef. “He’s such a girl!” Nimrat is so irritated by this remark that she grimly determines that “these idiots need to learn a lesson” and marches Pinkoo off to a tete-a-tete with a professional baker.

Pinkoo Shergil: Pastry Chef by Vibha Batra ( Scholastic India) is about Pinkoo’s training, the competition and persuading his very stern father to attend a baking competition. Papaji was of the opinion that “the kitchen is no place for a boy”. It is a fun, fun, fun book that upends a lot of stereotypes with a delightfully light touch. It is a book that generates a happy spot in one’s mind and at the same time gets various “messages” across without being didactic. The best one is saved for the last — whatever you do, give it your best shot and “don’t give up”, irrespective of ups and downs. The story is beautifully complemented by the zany black-and-white illustrations by Shamika Chaves. The buzz and excitement of the youngsters, who at the best of times are like little drops of mercury, is enhanced by the exuberant page design enabling certain words to pop out of the page. It emphasizes the rhythm of the text too. All in all, a gorgeous book!

Buy it. Share it. Read it. Donate it to school and community libraries. Pass on some of the love and joy. All of us could do with some.

4 August 2021

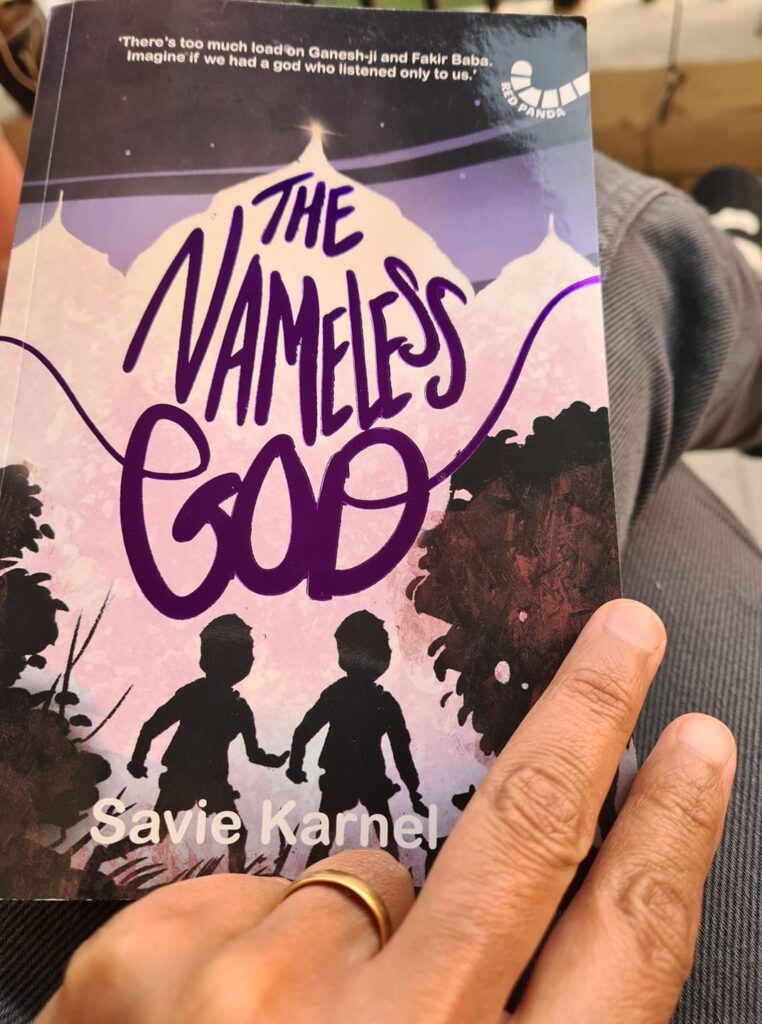

The Nameless God by Savie Karnel is an extraordinary novel for little kids. It is simply told. Set in Dec 1992 but in a nameless town where communal tensions erupt after the demolition of Babri Masjid on 6 December. It is a story about two friends — Noor and Bachchu — who find themselves caught in the communal riots that have broken out. On the eve of the riots, the boys had created a nameless god of their own and very sweetly, not knowing what items to use to decorate their makeshift altar, had gathered items associated with Hinduism and Islam. The boys saw no wrong in assimilating the two cultures they were intimately familiar with.

It is a story set in the near past but is so obviously a story that is affecting our present every day. It is a simply told story about very tough subjects that are not always openly discussed with children — religion, communalism, politics, secularism, the Constitution etc. At the same time, the basic messages of friendship, respect, kindness, humanity and India’s syncretic character come through strongly in the novel. It is obvious it is in our citizen’s DNA. And yet children are being slowly indoctrinated by the toxic prejudices of their elders. This has to be countered by sharing histories that are being scrubbed out of the public conscious and are being rapidly replaced by new ones that are being created. This is done effectively in The Nameless God.

This is a powerful story by a debut novelist with a strong voice, Savie Karnel . The author does not mince words. A story that will resonate with many and should be adopted by schools as a middle grade reader. It must also be translated and made widely available in the local languages. We need more of our own stories and histories being made available to school children than bombarding them with stories from other lands especially about Nazi Germany. Those too must be heard but we are at such a critical juncture of our nationhood that books like The Nameless God are essential to kick-start difficult conversations. It is time.

30 Jan 2021

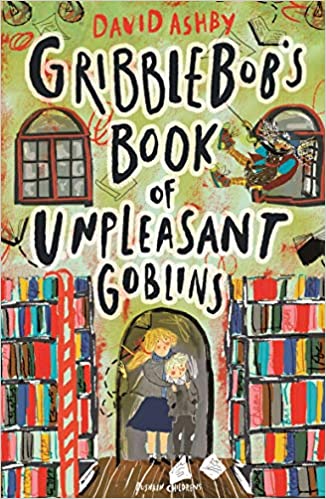

This book arrived today — Gribblebob’s Book of Unpleasant Goblins by David Ashby. My daughter immediately picked it up and was glued to it. Refused to budge. Ever so often one heard snorts of laughter and giggles. Or she would turn up with eyes shining and read out snippets from the book and repeat to say how much she was loving it. Made no difference to her whether I had understood the snippet or not, she was just very delighted with the story. It had magic, goblins, an invisible dog, children and the pace was just right.

Now I have been instructed to read it. You must.

Oh, BTW, David Ashby wrote this book to disprove a fortune teller who had predicted that David would never write a book. Well, now he has and if kid is to be believed, it is an “AWESOME BOOK!”

Cover illustration is by Jen Khatun and cover design by Anna Morrison.

25 Jan 2021

Update: On Instagram, David Ashby spotted the post and has been delighted with my daughter’s response. This is what he wrote:

I am so happy to hear that Sarah enjoyed reading #Gribblebob – and especially that she read bits of it out loud to you! When I wrote it I read each new chapter out loud to my children as a bedtime story and so it’s lovely to know that it still works that way. Please tell her that I think she’s an AWESOME READER!!

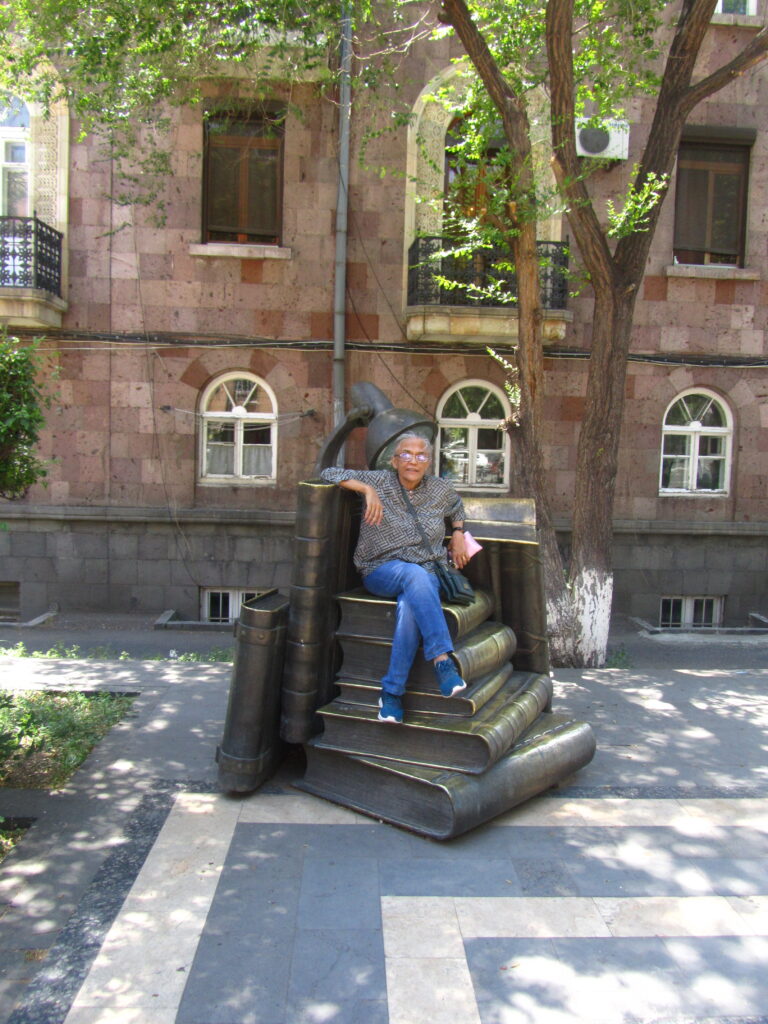

A couple of years ago, my mother, Dr. Shobhana Bhattacharji, went to Armenia to attend a conference on Byron. It is the annual gathering of Byronists that is held every year in a different country. While there she came across a library for children. It looked like an ordinary building on the outside. But once in, it was stupendous. Mum loved it. Here are some pictures from her visit.

2 Jan 2021

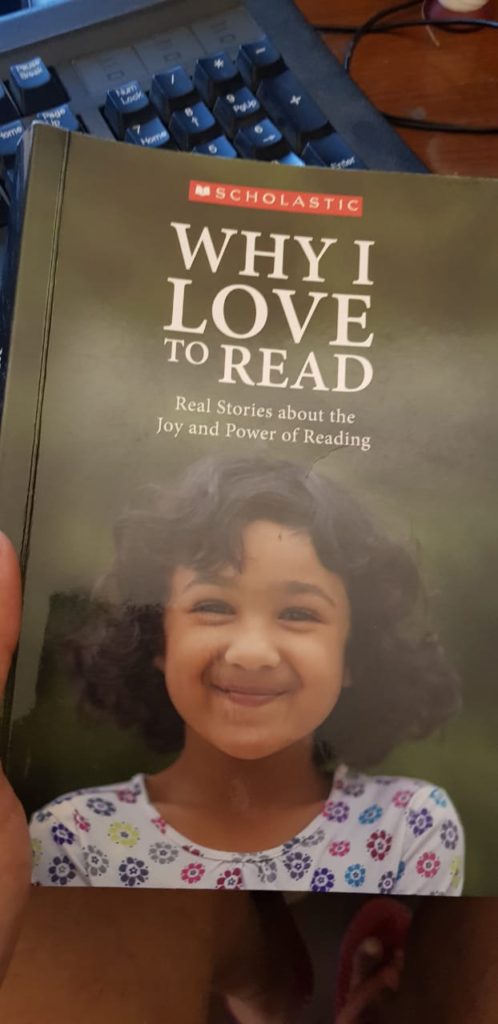

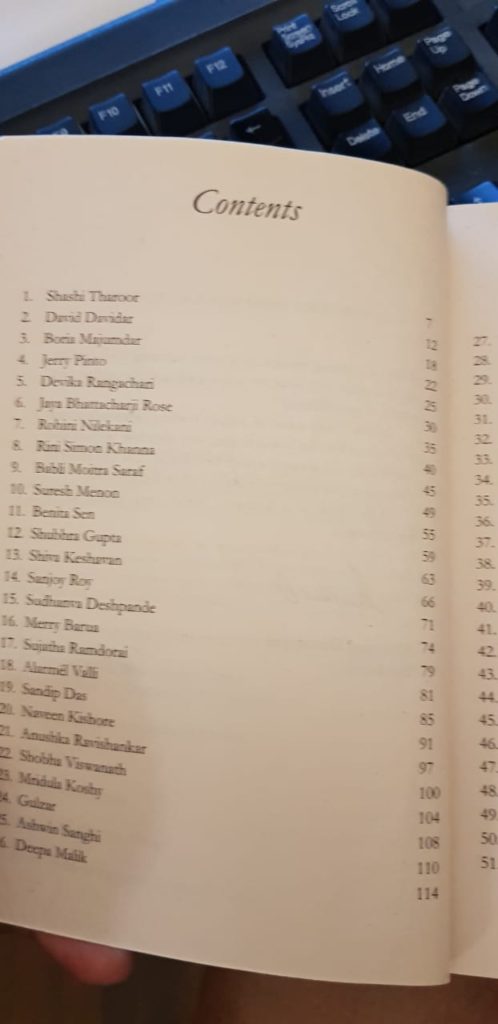

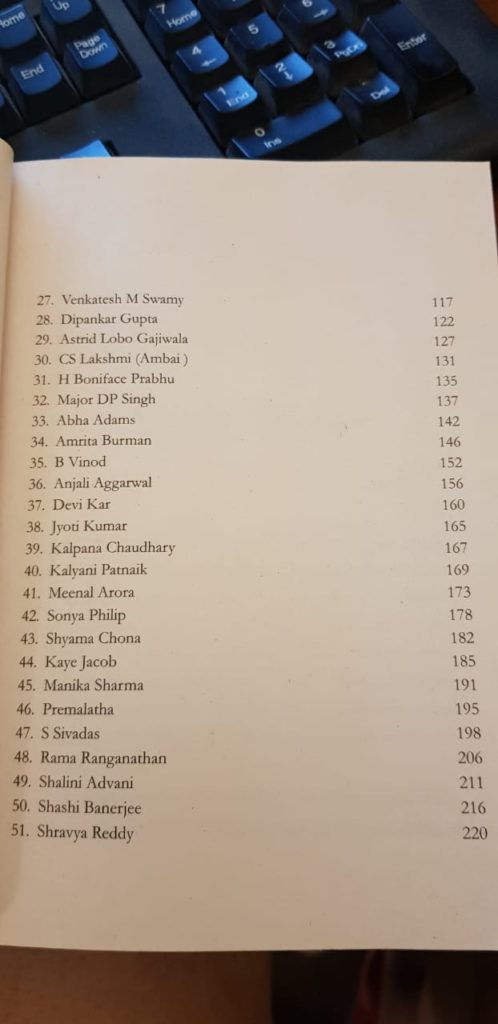

Last year Scholastic India published a marvellous collection of essays on reading. It is called Why I Love to Read: Real Stories about the Joy and Power of Reading. It is in keeping with the firm’s fundamental principle that reading opens up a world of possibilities. Reading is a lifelong skill. This anthology had a broad spectrum of contributors from across India. It included politicians, educationists, journalists, writers, publishers, poets, sociologists etc. I too contributed an essay. It was on how I managed to get my little girl to read modern English by introducing her to Malory’s Morte D’Arthur. The moment I introduced Sarah to medieval English where everything was spelt phonetically, the pennies dropped and she was able to make the relevant connections while reading modern English. So here is the essay that I am reproducing with the permission of the publisher.

****

“They even have books in their bathroom!” exclaimed a friend to other classmates while describing our childhood home. Little has changed. Recently my daughter reported how her classmates describe our home as being full of books wherever you look! My nine-year-old is convinced that books are her birth right. She demands books she issues from the library and enjoys immensely to be bought for her personal collection as well.

My family loves books. We have done so for generations. We have inherited books that are now more than a century old. My childhood bedroom which I shared with my twin brother had an entire wall made of deep wooden bookshelves. I had rows of books three deep and more stacked on top.

I do not know what sparked my love for reading. It could have been my mother who decided to read out the texts she was teaching to her undergraduate students. Mum is a fantastic storyteller. So by the time we were six we knew our Shakespeare, Dracula along with breathless Piglet saying “Heff, Heff, Heffalump” from Winnie-the Pooh or she made up wonderfully imaginative tales. Or it could be my maternal grandfather who after lunch would tell us about the outrageous escapades about Laurel and Hardy traipsing through North East India – all totally made up of course! (My Nana as a senior civil servant had visited the region in the 1960s and 70s.) Or my paternal grandmother who would tell us stories about Shaikh-Chilli and other folktales at bed time. Or it could have been my bedridden great-grandmother who would tell us stories about Delhi and Dalhousie during British Raj including of C.F. Andrews or Charlie Dada as she referred to him fondly. He would arrive regularly at her home in Dalhousie with nothing except the clothes on his back. After every visit she would send him off on his travels once more with a bistar-band/ bedding holdall and clothes but he would inevitably distribute them to a more needy soul. My father is not much of a storyteller in words but as a photographer he is astounding. He brought home interesting guests, inevitably mountaineers and photographers, who would regale us with amazing tales of climbing some of the highest peaks in the world or taking photographs under extraordinary circumstances.

It was a short step from being surrounded by stories to reading the books lining our shelves. My mother too developed a neat trick of stocking our bookshelves with books just a little ahead of our biological years so we were never out of reading matter. Alternatively she would borrow huge piles of books from her college library and suggest books of all kinds – ranging from Georgette Heyer romances, Gerald Durrell’s animal stories, Homer, Malory, historical fiction to science fiction. We were well brought up kids. We even knew Asimov’s Three Robotic Laws fairly soon! Once mum realised I was getting frightfully bored by sixteenth century English Literature, she suggested a range of historical novels of the Elizabethean period. I developed a lifelong soft corner for it. As children we were encouraged to read anything that came our way. We spent most of our free time reading.

Initially I read what existed at home but slowly developed a passion for buying books and later even inherited personal libraries. I have an eclectic and vast collection of books. Now an entire floor in my parent’s home has floor-to-ceiling bookshelves lining the walls. In my marital home I have a study (and more) that is lined with bookshelves — anything to prevent my forming book towers! Even now my happiest moments are when I am surrounded by books and reading. It gives me peace. It is also as a parent I realise excellent role modelling. Children imitate their parent’s actions.

As a parent now I encourage my daughter to read anything she likes. Digital entertainment is rationed. When she was struggling to understand how English is written and spoken, I introduced her to my beautiful of Aubrey Beardsley’s Malory’s Morte D’Arthur. Very soon the kid was able to “read” the story as Middle English was written exactly as phonetics is practised. It made it even more fascinating that the stories were about her favourite trio – King Arthur, Merlin and Queen Guinevere. One of her favourite past times is to read the spines of my books. (She even began reading this essay and wanted to know why I was writing about reading? It puzzled her – why on something as basic as reading?) The best inheritance I can give my daughter is of reading as a valuable lifelong skill and not just for leisure.

For now she is a happy kid who said to me reading out aloud from Diary of a Wimpy Kid “This is so easy to read. It is like an early learners reading!”

Shhhhhhh! We have a reader in the making!

17 April 2020

Susan Van Metre is the Executive Editorial Director of Walker Books US, a new division of Candlewick Press and the Walker Group. Previously she was at Abrams, where she founded the Amulet imprint and edited El Deafo by Cece Bell, the Origami Yoda series by Tom Angleberger, the Internet Girls series by Lauren Myracle, They Say Blue by Jillian Tamaki, and the Questioneers series by Andrea Beaty and David Roberts. She lives in Brooklyn with her husband, Pete Fornatale, and their daughter and Lab mix.

Susan and I met when we were a part of the Visiting International Publishers delegation organised by the Australia Council and Sydney Writers Festival. It was an incredibly enriching time we spent with other publishing professionals from around the world. Meeting Susan was fabulous as Walker Books is synonymous with very high standards of production in children’s literature. Over the decades the firm has established a formidable reputation. Susan very kindly agreed to do an interview via email. Here are lightly edited excerpts.

1. How did you get into

publishing children’s literature? Why join children’s publishing at a time when

it was not very much in the public eye?

I never stopped reading children’s books, even as a teen and young adult. I have always been in love with story. I was a quiet, lonely young person and storytelling pulled me out of my small world and set me down in wonderful places in the company of people I admired. I couldn’t easily find the same richness of plot and character in the adult books of the era so stuck with Joan Aiken and CS Lewis and E Nesbit and Ellen Raskin. And I loved the books themselves, as objects, and, in college, had the idea of helping to make them. I applied to the Radcliffe Publishing Course, now at Columbia, met some editors from Dutton Children’s Books/Penguin there, and was invited to interview. Though I couldn’t type at all (a requirement at the time), I think I won the job with my passionate conviction that the best children’s books are great literature, and arguably more crucial to our culture in that they create readers.

2. How do you commission books? Is it always through literary agents?

Most of the books I publish come from agents but occasionally I’ll reach out to a writer who has written an article that impressed me and ask if they have thought of writing a book. Recently, I bought a book based on hearing the makings of the plot in a podcast episode.

3. How have the books you read as a child formed you as an editor/publisher? If you worry about the world being shaped by men, does this imply you have a soft corner for fiction by women? ( Your essay, “Rewriting the Stories that Shape Us”)

What a good question. I definitely look for books with protagonists that don’t typically take centre stage, whether it’s a girl or a character of colour or a character with a disability. I have always been attracted to heroes who are underdogs or outsiders, ones that prevail not because they have special powers or abilities but because they have determination and heart. I am in love with a book on our Fall ’19 list, a fantasy whose hero is a teen girl with Down syndrome. It’s The Good Hawk by Joseph Elliott. I have never met a character like Agatha before—she’s all momentum and loyalty. Readers will love her.

4. Who are the writers/artists that have influenced your publishing career/choices?

I am very influenced by brainy, hardworking creators like Ellen Raskin and Cece Bell and Mac Barnett and Sophie Blackall and Jillian Tamaki. I admire a great work ethic, outside-the-box thinking, an instinct for how words and images can work together to create a richly-realized story, and respect for kids as fully intelligent and emotional beings with more at stake than many adults.

5. As an employee- and author-owned company, Candlewick is used to working collaboratively in-house and with the other firms in the Walker groups. How does this inform your publishing programme? Does it nudge the boundaries of creativity?

There is so much pride at Walker and Candlewick. Owning the company makes us feel that much more invested in what we are making because it is truly a reflection of us and our values and tastes. Plus, we only make children’s books and thus put our complete resources behind them. There are no pesky, costly adult books and authors to distract us. And I think the strong lines of communication amongst the offices in Boston, New York, London, and Sydney mean that we have a good global perspective on children’s literature and endeavour to make books with universal appeal. I think all these factors contribute to innovation and quality.

6. You have spent many years in publishing, garnering experience in three prominent firms —Penguin USA, Abrams and Candlewick Press. In your opinion have the rules of the game for children’s publishing changed from when you joined to present day?

Oh, definitely. When I started, children’s publishing was a quiet corner of the business, mostly dependent on library sales. There was no Harry Potter or Hunger Games or Wimpy Kid; no great juggernauts driving millions of copies and dollars. And not really much YA. YA might be one spinner rack at the library, not the vast sections you see now, full of adult readers. Now children’s and YA is big business and mostly bright spots in the market. The deals are bigger and the risk is bigger and the speed of business is so much faster!

7. Do you discern a change in reading patterns? Do these vary across formats like picture books, novels, graphic novels? Are there noticeable differences in the consumption patterns between fiction and nonfiction? Do gender preferences play a significant role in deciding the market?

I think we are in a great time for illustrated books, whether they are picture books, nonfiction, chapter books, or graphic novels. And now children can move from reading picture books to chapter books to graphic novels without giving up full colour illustrations as they age. And why should they? Visual literacy is so important to our internet age—an important way to communicate online.

8. One of the iconic books of modern times that you have worked upon are the Diary of a Wimpy Kid series. Tell me more about the back story, how it came to be etc. Also what is your opinion on the increasing popularity of graphic novels and how has it impacted children’s publishing?

I am not the editor of the Wimpy Kid books—that’s Charles Kochman—but I was lucky enough to help sign them up and bring them to publication as the then head of the imprint they are published under, Amulet Books. Charlie comes out of comics so when he saw the proposal for Wimpy Kid, which had been turned down elsewhere, he understood the skill and appeal of it. I have NEVER published anything that took off so immediately. I think we printed 25,000 copies, initially, and we sold out of them in two weeks. It showed how hungry readers were for that strong play of words and images, and how they longed for a protagonist who was flawed but who didn’t have to learn a lesson. Adult readers have many such protagonists to enjoy but they are rarer in kids’ books.

9. Walker Books are inevitably heavily illustrated, where each page has had to be carefully designed. Have any of your books been translated? If so what are the pros and cons of such an exercise?

Our lead Fall title, Malamander, is illustrated and has been sold in a dozen languages. I think illustration can be a big plus in conveying story in a universally accessible way.

10. The Walker Group is known for its outstanding production quality of printed books. Has the advancement of digital technology affected the world of children’s publishing? If so, how?

I think they incredible efficiency of modern four-colour printing has allowed us to spend money on other aspects of the book, like cloth covers or deckled edges. That sort of thing. Children’s books are incredible physical objects these days.

11. Walker Books’ reputation is built on its ability to be creatively innovative and constantly adapt to a changing environment. How has the group managed to retain its influence in this multimedia culture?

First, thank you for saying so! I think the rest of media still looks to book publishing for great stories and as a house that has always invested in talent, we are lucky enough to have stories that work across many forms of media.

12. Have any of books you have worked upon in your career been banned? If so, why? What has been the reaction?

Yes. In fact, I am working with Lauren Myracle on a young adult novel, publishing in Spring ’21, called This Boy. Lauren is the author of the ttyl series, which was on the ALA’s Banned Book list for many years. It was challenged for its depictions of teenage sexuality. I was raised to be modest and rule following so my personal reaction was horror—especially when parents started phoning me directly to complain—but I feel so strongly that kids and teens deserve to read about life as it really is—not just as we wish it would be. So I came to be proud of the designation. Nothing is scarier than the truth.

Bibliography:

Hannah Lambert (2010) Sebastian Walker and Walker Books: A Commercial Case Study, New Review of Children’s Literature and Librarianship, 15:2, 114-127, DOI: 10.1080/13614540903498885. Published online: 03 Feb 2010.

25 Sept 2019