The Bling Factory

Over a decade ago I did a regular column for Business World. It was on the business of publishing. Here is the original url.

***

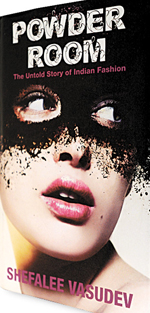

In 1999, an exhibition was organised in Delhi to support artisans in cyclone-hit Orissa. At the event, I spotted a young student working with an equally young Patachitra artisan. The way the student interacted with the artisan seemed odd. While she was ‘instructing’ the man to do things, the artisan meekly obeyed her and created dull Patachitra creations. I knew the man. He had retold some classic tales beautifully on dried palm leaves, and was using his art to record contemporary events and their impact. He had an entire Patachitra telling the story of lynched missionary Graham Staines. Hence, the lack of sensitivity of the student was bewildering. Equally or even more bewildering are stories that Shefalee Vasudev tells about the fashion industry in Powder Room. The book is a gripping narrative of the fashion eco-system in India. Vasudev, former India editor of fashion magazine Marie Claire, offers a strong perspective and weaves an excellent story about how fashion brands are lapped up by the nouveau riche and by the powerful. The bling factor is so high. Sample this: at an exclusive designer exhibition in Ludhiana, the author noticed a woman wearing six big brands, all at the same time, and wanting to buy some more. Vasudev starts with an admission that till she was in Class 12, she had not heard of Coco Chanel. But she goes on to prove that she is arguably the best hand around to decode the glam factory. She documents the aspirations of many of those who struggle to rise to the top within the fashion fraternity and the evolution of those who stay ahead by working hard and adapting. Vasudev interviewed over 300 people for the book, including people in small towns and big cities, well-established designers, shop assistants with dreams of their own, struggling and successful models and tailors. Statistics reeled out in the book explain the dynamics propelling the fashion market in India to the levels where it is today and beyond. For instance, clothing is a $33.2 billion dollar industry in India and accounts for the second largest pie in the country’s spending chart. In 2007, a McKinsey report — ‘The Bird of Gold’ — on India’s consumer market said there would be over 570 million middle class Indians by 2025 and India would be the world’s fifth-biggest consumer market. By July 2012, Louis Vuitton had 2,468 stores worldwide with 495 in Asia, and its growth rate in India was pegged above 20 per cent in 2011. A few months ago, consultancy firm AT Kearney said the fashion market was growing at 20 per cent and would reach $15 billion by 2015. But the author says fashion is a labour dominated industry, which includes not just the brands, but also artisans and craftsmen who, until recently, were the second largest contributors to the Indian economy. In many cases, it is creating a dichotomy in the fashion world. Probably, much of this is set to change as is evident by the recent news of Louis Vuitton Moet Hennesy buying an 8 per cent stake in Fabindia. Vasudev builds a natural narrative and creates sympathy for the profiled. She understands their ambitions and compulsions, but is emotionally detached to encapsulate relevant details. Hers is an in-depth understanding of the industry — “it is not a clean, decent industry… for those who want to hold on to values, fashion is not the easiest place to be in.” She, too, became disillusioned with the industry, losing interest in her job at Marie Claire as she was not sure what an editor’s job meant in a fashion magazine “except for being the smartest cookie in a team”. She felt it was “brochure journalism” and you had to figure out the “least common denominator between advertisers, celebs, the marketing wish list, personal obligations, put seven cover lines out of which three had to be international and get it right”.

15 Jan 2021