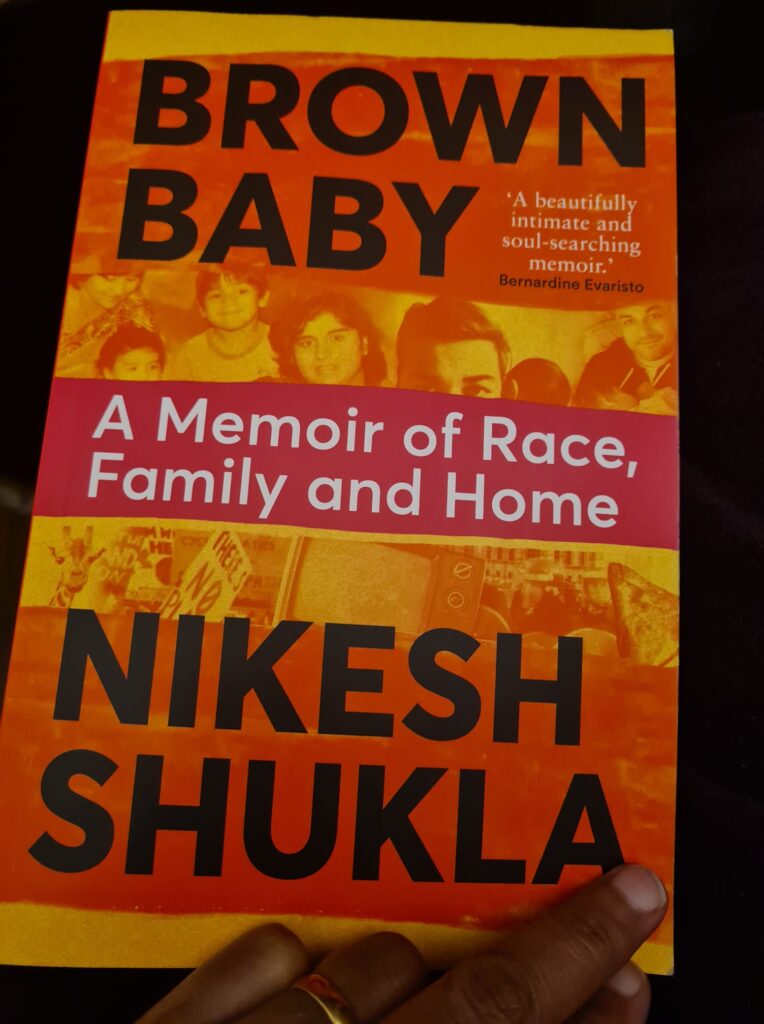

Nikesh Shukla’s “Brown Baby”

In 2019, en route to attending the Jaipur Literature Festival, Nikesh Shukla lost his necklace at Heathrow Airport. It was very precious as it contained some of his mother’s ashes. He was extremely distraught. I happened to meet him as well and his grief was palpable. I will not forget that shattered look of his. He was numb. He put out a tweet announcing the loss of his locket. The power of social media being what it is, after more than 10,000 retweets, the necklace was discovered. At least that is what this article states: https://www.indiatoday.in/…/author-loses-necklace-with…

Brown Baby is Nikesh Shukla’s memoir that’s opening line refers to his mother’s death. It is a powerful, all-consuming moment in his life and he forever returns to it in his book. The loss of a dear one, especially a parent, is devastating. Shukla’s mother passed away due to lung cancer and once the death knell had been sounded by the oncologist, the family was heartbroken. A grief and despair that took ages and ages to get back their lives to some semblance of normalcy. The structure of Brown Baby is ostensibly a conversation with his elder daughter, Ganga, who seems to have been born after his mother died but he also uses the book as a reason to talk about racism in UK in minute detail. It is an interesting space for him to explore as he realises the immense responsibility that comes with becoming a parent. How much does one teach the munchkins, how do they navigate their world, how do they straddle worlds etc? He reminiscences how his mother brought up his sisters and him — children of Asian origin growing up in a white country. How they learned to preserve their culture ( food forming a large part of their life) and yet learned how to survive racist slurs and develop identities of their own. While his anger in the first half of the book is understandable and how much of it defines him as an author, publisher and parent today, some of it is also self-defeating. His arguments for being a minority because of his skin colour in a country where white is privileged are based on firsthand experience and other facts he has collected, but he makes the same majoritarian mistake that he is accusing the whites of not recognising the variety of cultures that now exist in modern UK. For example, he falls into the same trap by eliding the definition of India being linked to Hinduism whereas Hindus constitute the majority. He says, “In India, the Ganges river is worshipped as representative of the goddess Ganga.” A true statement that would have read as a more powerful statement if he had clarified by adding that “In India, the Ganges river is worshipped [by the Hindus]…”. In this day and age, when everyone is super-sensitive about identity and cultures, it stands to reason that someone like Nikesh Shukla who is very influential globally in the world of letters would be a little more careful in the choice of his words. He has a responsibility not only towards his daughter who he is introducing to their Indian roots, but also to his multi-cultural readers and the Indian diaspora. His word would carry more weight if he recognised these finer distinctions. In India, all of us are different shades of brown, but thrive in a syncretic and casteist culture, so it is not as easy to make these distinctions between white and brown, but these different identities exist. Yet, we manage to live.

The second half of Brown Baby is far calmer and easier to read. He discusses in detail what it means to talk in Hindi, to be a Hindu in Britain, be an Asian etc. There is a fascinating anecdote he shares about submitting a manuscript to a literary agent who dismisses it for not being authentic Asian. Understandably it makes Shukla hopping mad. Anyone would be under such circumstances. Fortunately he puts this anger to good use and has established The Good Literary Agency with Julia Kingsford.

Inspired by a desire to increase opportunities for representation for all writers under-represented in mainstream publishing, we are focused on discovering, developing and launching the careers of writers of colour, disability, working class, LGBTQ+ and anyone who feels their story is not being told in the mainstream.

It also explains this passage in the concluding pages of Brown Baby:

What does it mean to be British when conversations around the subject have their core in protecting Britain’s whiteness? When the multiculturalism ‘debate’, if you wish to call it such doesn’t scratch any deeper than ‘saris, steel bands and samosas’. Where debate events by sixth form debate clubs like the Institue of Ideas present multiculturalism as a threat to the West, as something worth of debate, as if we never got past that basic point, as if the only conversation we can have about immigration and the place of people of colour in society is about their inherent threat to Western values, rather than how we come to a decision about what an inclusive Britishness looks like.

Nikesh Shukla’s heart is in the right place. He knows how to channel his anger that wells up due to the injustice and discrimination he has either faced or witnessed. He wishes to correct some of these social ills by ensuring that his daughters generation learns to be proud of their identities. A spirit his mother imbued him with as well. At the same time by speaking clearly on these issues and offering an inclusive and diverse publishing platform to others, he hopes to create enough of a difference in the mainstream that will enable everyone to be recognised as equals, irrespective of colour, religion, sexuality etc. The mantra in his memoir seems to be that it is imperative everyone learns to be humane to others. This sensitive understanding needs to prevail. It is only then racist/casteist/communal attitudes will be tackled. Otherwise they will continue to exist for generations.

This is a memorable book. Worth reading.

20 Feb 2021