“Maps of Delhi” Pilar Maria Guerrieri

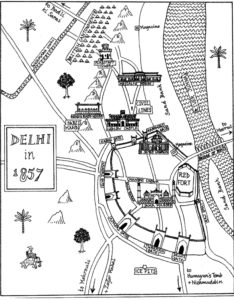

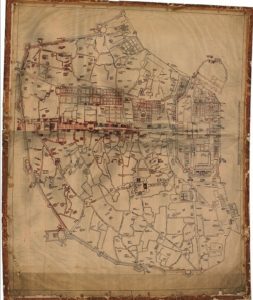

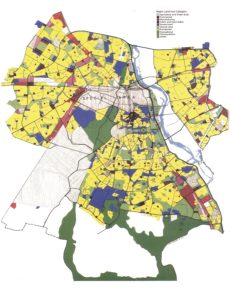

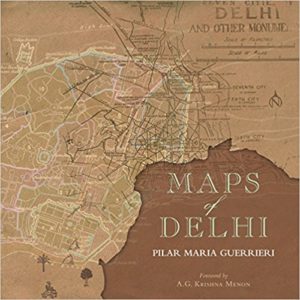

Maps of Delhi is a rich collection of historical maps after 1803 till the Master Plan of Delhi 2021. Pilar Maria Guerrieri as a doctoral student of architecture started scouring the National Archives of India and institutions for maps. Studying maps helped her understand the evolution of Delhi as a city while making it possible to “consider the link between empty spaces and built areas as well as the association between agricultural and non-agricultural land. They distinguish public buildings, the disposition of plots, the types of housing, and the density of the urban fabric in addition to interpreting the structures innervating the territory, like watercourses, canals, routes, railroads, and roads, as also the order or constellation of the countryside and the correlation between villages and cities. Effectively and particularly in the illustration of Delhi, these maps delineate, more so demarcate and define, the spread of several urban settlements, planned or organically organised, and provide a pragmatic synopsis of how they are juxtaposed, concurrent or interlaced, with each other”.

Maps of Delhi is a rich collection of historical maps after 1803 till the Master Plan of Delhi 2021. Pilar Maria Guerrieri as a doctoral student of architecture started scouring the National Archives of India and institutions for maps. Studying maps helped her understand the evolution of Delhi as a city while making it possible to “consider the link between empty spaces and built areas as well as the association between agricultural and non-agricultural land. They distinguish public buildings, the disposition of plots, the types of housing, and the density of the urban fabric in addition to interpreting the structures innervating the territory, like watercourses, canals, routes, railroads, and roads, as also the order or constellation of the countryside and the correlation between villages and cities. Effectively and particularly in the illustration of Delhi, these maps delineate, more so demarcate and define, the spread of several urban settlements, planned or organically organised, and provide a pragmatic synopsis of how they are juxtaposed, concurrent or interlaced, with each other”.

In his Foreword to the book, well-known architect, A. G. Krishna Menon says the geneaology of Pilar Maria Guerrieri’s methodology can find its roots in the Italian acdemic tradition of understanding a city by studying its maps and drawings or the so-called “Italian school of planning typology’ which developed theoretical approaches based on analysing ancient cartography of cities as a foundation and core of their design interventions. “These pioneering initiatives established the Italian academic culture of physical planning, which becomes evident in the manner Guerrieri studied Delhi.”

Cartography is an exacting technique through which areas of territory are represented. Maps have always been extremely useful to governments, military commanders, engineers and increasingly civilians. Earlier they were largely representative but with increased knowledge and advanced measurement tools it became possible to create more and more accurate maps.

In the Indian sub-continent for centuries people have relied on the patwaris or the lowest level of state functionary in the revenue collection system to record land use. These individuals are to be found whereever there is habitation and in the older settlements the records stretch back decades, sometimes even centuries. Maps are a repository of a lot of sensitive information as well.

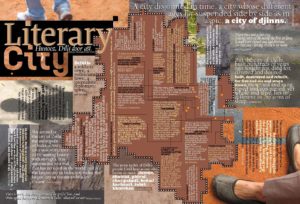

Today maps are used increasingly in real time particularly on digital devices using a complex network of satellites, an extensive network of cables and Internet connectivity. Fewer individuals rely on printed maps, less and less of which are being published too. It may be a convenient tool to access a map on a smartphone but over a period of time it will become evident that a significant way of recording history and land use will be lost forever. For now it is not very clear who is storing this information since there are multiple agencies and individuals recording it. In the future researchers like Guerrieri may find it challenging to seek the information they desire since data will be non-existent or available in formats that newer technologies may be unable to access. At least printed maps such as those included in Maps of Delhi remain available over time. While we are on maps of Delhi here is an interesting one commissioned by Raghu Karnad as editor, Time Out — Literary Map. It was designed by Akila Seshayee.

Interestingly enough even to reproduce the few images for this article required new permission from the National Archives of India. Some of the maps though published in the book cannot be reproduced anywhere else for their sensitive nature and only one-time use has been granted for the book.

Maps of Delhi is a heavily illustrated book in four colour. A scrumptious production worth possessing for the lay reader or the specialist. It makes a wonderful companion to Mapping India also published by Niyogi Books.

Maps of Delhi is a heavily illustrated book in four colour. A scrumptious production worth possessing for the lay reader or the specialist. It makes a wonderful companion to Mapping India also published by Niyogi Books.

The following images from the book are used with permission.

Pilar Maria Guerrieri Maps of Delhi ( Foreword by A.G. Krishna Menon) Niyogi Books, New Delhi, India, 2017. Hb. Rs. 4500 / £65 /$85

18 June 2017