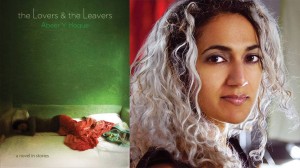

Abeer Y. Hoque “The Lovers and the Leavers”

But it hadn’t been the smell of Indian food that had offended Sailan. It was Appa. Gabriel had never considered their father’s post-work rituals consciously until that day. Upon returning home, Appa would go upstairs and remove his suit, uniformly grey or navy, leave on a thin white singlet that stretched over his ballooning waist, and tie on a well-worn lungi. Downstairs, he would gather the newspapers from the hall table where his mother had discarded them, and get an apple from the kitchen. Then he’d squat in the corner of the living room, eat the apple, and read the papers. What was wrong with wearing pants? Sailan had asked. Or maybe squatting in the study instead of the living room?

But it hadn’t been the smell of Indian food that had offended Sailan. It was Appa. Gabriel had never considered their father’s post-work rituals consciously until that day. Upon returning home, Appa would go upstairs and remove his suit, uniformly grey or navy, leave on a thin white singlet that stretched over his ballooning waist, and tie on a well-worn lungi. Downstairs, he would gather the newspapers from the hall table where his mother had discarded them, and get an apple from the kitchen. Then he’d squat in the corner of the living room, eat the apple, and read the papers. What was wrong with wearing pants? Sailan had asked. Or maybe squatting in the study instead of the living room?

‘The study is crowded,’ Appa said mildly, choosing to reply to the second query, combing through the few remaining hairs on top of his head.

‘Because you use it for storage,’ Sailan said.

Appa shrugged. ‘There’s enough space in the living room for all of us.’

‘The space is not the point. We can’t use the living room for entertaining. I’d just like to bring my friends over without feeling as if we’re entering a television programme about displaced immigrants.’

It was true that their living room didn’t look like any Catalan living room Gabriel had been in. The paisley print curtains didn’t match the plastic-covered furniture, and there were piles of papers in all the corners. Appa never cared for how things appeared, but his contempt for Sailan’s tone overcame his disregard.

‘We are displaced immigrants,’ he said, in an uncharacteristically sharp way.

( p.125-7)

Abeer Y. Hoque’s first book, The Lovers and the Leavers, is a collection of twelve interlinked short stories with photographs and poetry interspersed. The stories revolve around a bunch of characters, spanning a few years, though it is never let on in numbers. You can only gauge time by the different points of life the characters are at. Some were toddlers but when the book comes to an end, they are married. These are stories told from different gendered and social perspectives. These stories are about different kinds of love and inevitably the pain of being rejected that are at the crux of the stories. But it is the manner in which these are told that is so refreshing.

About a decade ago, fiction written by the subcontinent diaspora, especially of those settled in America was popularly referred to as ABCD or “American Born Confused Desi”. A story had to be told by the immigrants. There are many writers who have established their name doing it but there is a new generation of writers emerging. Writers who are poised, at ease with their dual identity — of being Americans and of belonging to the land they originated from, it shows in their confident style of writing and the wonderful ability to blend the various cultures they are privy to. Abeer Y. Hoque belongs to this category. Gently, forcefully and with grace she is able to flit between cultures evident in the use of language — “sophomoric sexuality”, “old-fashioned bideshi manners”, and “coloured monkeyboy”. To be able to talk about different cultural experiences without being patronising and yet, with searing insight she communicates the feeling of alienation apparent at times. For instance the reference to “their ‘gora’ meals as they called them, more for the pale shade of the food than the race of people. Bags of potato chips, popcorn, rolls of cookie dough on special occasions.” (p.206)

The Lovers and the Leavers is a fine example of stylish storytelling. It is by a writer who seems to be at peace with being identified as a Bangladeshi American writer, born in Nigeria, and with no qualms about discussing life as she has experienced it — a mixed bag of cultural influences. I love it.

Abeer Y. Hoque The Lovers and the Leavers Fourth Estate, HarperCollins Publishers, 2015. Hb, pp. 240. Rs. 499

14 August 2015