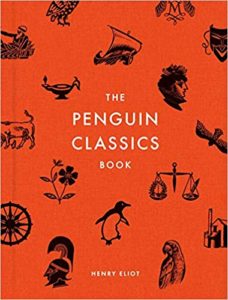

I interviewed Henry Eliot, Creative Editor of Penguin Classics in the UK after reading the marvellous The Penguin Classics Book he has authored. It is a beautiful historical documentation of the Penguin Classics list. This book spans world literature from the 21st century BCE to the First World War. The list was launched by the legendary translator and scholar Prof. E. V. Rieu at the invitation of the founder of Penguin Books, Sir Allen Lane. The sales of 130 titles Prof E V Rieu launched sold more than a million copies a year. This impressive book sales record is more or less unsurpassed even now. ( Scroll re-published the interview on their website on 9 Dec 2018. Here is the link. )

I interviewed Henry Eliot, Creative Editor of Penguin Classics in the UK after reading the marvellous The Penguin Classics Book he has authored. It is a beautiful historical documentation of the Penguin Classics list. This book spans world literature from the 21st century BCE to the First World War. The list was launched by the legendary translator and scholar Prof. E. V. Rieu at the invitation of the founder of Penguin Books, Sir Allen Lane. The sales of 130 titles Prof E V Rieu launched sold more than a million copies a year. This impressive book sales record is more or less unsurpassed even now. ( Scroll re-published the interview on their website on 9 Dec 2018. Here is the link. )

Henry Eliot has also written Follow This Thread and Curiocity: An Alternative A-Z of London(with Matt Lloyd-Rose).

The Penguin Classics Book comes across as a pure labour of love. It also fulfils a very

essential task of being a rich historical documentation of a sterling list while being a repository of world literature translated in to English. Henry Eliot’s comments in the book about Dr Rieu’s vision and his intention of housing only the well-known texts as translations on this list is a good reference point for many of the ongoing discussions in the literary world about translations. In fact Dr Rieu’s classic translation of Homer’s

The Odyssey has been prescribed for decades by universities around the world. Dr. Rieu favoured prose but this was (thankfully!) reviewed by his successor, Betty Radice. While reading

The Penguin Classics Book I came across a fabulous discussion between Dr E.V. Rieu and Rev. J. B. Phillips on

translating the Gospels, recorded on 3 Dec 1953. Dr Rieu is very clear on what he deems to be a good translation — the principle of ‘equivalent effect’ and that it holds well when read aloud. A principle that Henry Eliot confirmed is still in place!

*****

Here are excerpts from the conversation:

1. How was this project conceptualised? How long did it take to execute from start to finish?

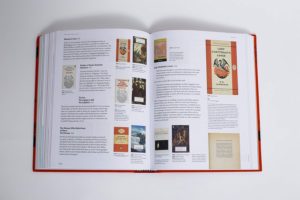

When I joined Penguin Classics nearly three years ago, one of the first things that struck me was the size of the list. Over the last 70 years it has grown so huge – it now has over 1,200 Penguin Classics and 1,000 Penguin Modern Classics – and it is difficult now for a reader to get a handle on this vast list. We began talking about ways to help  readers to navigate the list, to assist them in making sense of it: we imagined a classics ‘museum’ with some big galleries and some hidden corners through which readers could wander and explore and make discoveries. In the end we didn’t build a physical museum but we created a book, which allows the reader to hold the entire list in their hands: now you can get the measure of the entire list and I hope this will give readers the confidence to explore the series and discover wonderful new titles and authors to read.

readers to navigate the list, to assist them in making sense of it: we imagined a classics ‘museum’ with some big galleries and some hidden corners through which readers could wander and explore and make discoveries. In the end we didn’t build a physical museum but we created a book, which allows the reader to hold the entire list in their hands: now you can get the measure of the entire list and I hope this will give readers the confidence to explore the series and discover wonderful new titles and authors to read.

We began these discussions about two and a half years ago and decided to make the book a few months later. It took me about a year to write and then another year for the design to come together for printing.

2. In your opinion what are the key characteristics of Penguin Classics? How has it evolved over the years?

Penguin Classics has always aimed to present the best books from literatures across the world and to make them accessible to a general readership. It has always prided itself on high quality design and production values. These things have remained unchanged; some things have changed, however:

- For the first forty years the list was a translation list only: there were no English-language Penguin Classics. These were published in a parallel sister series called Penguin English Classics, which was eventually absorbed into Penguin Classics in 1985.

- The first series editor, E. V. Rieu, had a preference for prose translations of verse and he insisted on minimal critical ‘apparatus’ other than a short introduction; his successor, Betty Radice, however, preferred verse translations and she responded to an increased interest from US students by including more scholarly appendices.

- The list’s horizons have also expanded over the years. Rieu had a prejudice against German literature, for example, and Radice made a concerted effort to introduce more Chinese literature. The job of the editors today is to identify the many gaps on the list and attempt to fill them.

3. Even though over the years the list was brought in-house rather than work with remote editors, do the team of editorial directors supervising this list have language specialists advising them on developing the literature in other languages and assessing the final translation?

Yes – the editors have expert contacts in the worlds of academia and publishing, whom they consult.

[ JBR: This is fascinating because this is the manner in which academic and journal publishing happens – to have external advisors, readers and experts guiding the publishing programme. It is a brilliant way in which to test the strength of a list and/or establish a new one.]

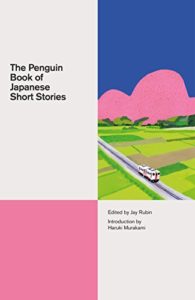

4. What is truly remarkable is that The Penguin Classics Book is as up-to-date as possible. For  instance, the new Japanese stories (ed. Jay Rubin) edition with an introduction by Haruki Murakami is included. How did this inclusion happen?

instance, the new Japanese stories (ed. Jay Rubin) edition with an introduction by Haruki Murakami is included. How did this inclusion happen?

Thank you! We have included every Penguin Classic that is in print now – the book is up-to-date to the end of 2018 (and even further in a couple of cases – the publication of Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy was delayed to 2019, but we still decided to keep it in the book). The book is roughly organised chronologically and covers literature written before the end of the First World War, but of course this poses a problem in the case of anthologies. We decided to include anthologies at the point in the book that coincides with their earliest work. The Penguin Book of Japanese Short Stories makes it in on these criteria – it was published in June 2018 and the first story was written in the late 19th-century.

5. Would it be correct to assume that the digital age with its stress on visual images created an opportunity to publish in print the rich history of such a magnificent archive?

I’m not sure — in a way the process was quite old-fashioned. There are over 3,000 images in the book and we got them by photographing all the covers individually. I spent two solid weeks in the Penguin archive working with two photographers in order to capture them all. Now that we have the images, however, I’m sure there will be lots of further uses for them, many of which will no doubt be digital.

[ JBR: Perhaps I did not make myself very well clear in the questioning. I meant if the visual world of the digital space has not impacted the decision to create a visually beautiful edition in print? The previous volumes of Penguin covers have always been paperbacks, in four colour, but nowhere near as beautiful as this edition is.

HE: Thank you — much appreciated! Maybe . . . I think we’re all frustrated by the rigid way in which Amazon displays its book covers – so maybe this was a subconscious reaction to that.]

6. Which titles that have become extinct in the backlist would you recommend resurrecting for a modern reader? Do you think titles showcased in “The Vaults” section may have a future life as digital editions rather than in print?

About ten years ago the editors tried resurrecting a few Penguin Classics titles which had gone out of print and the experiment wasn’t a huge success. I’m sure there are exceptions, but it seems that when something goes out of print, it goes out of print for a reason: there just isn’t the demand from readers.

It might be possible to offer digital editions of these titles, but there might also be an argument for ‘weeding out’ the titles that don’t sell so well, so that the quality and relevance of the whole list remains strong.

7. The book cover designs are always distinctive. For years the Penguin Classics were defined by the deep black, then a deep black with a photograph and a coloured border etc. Why and how did these cover designs change or does it depend entirely upon the whimsical fancies of the editor in charge?

Penguin Classics has had four different designs over the years. The first, designed by John Overton in 1946 and refined by Jan Tschichold in 1949, had a border that was colour-coded by language and an illustrative woodcut in the centre. The second, introduced in 1963 by Germano Facetti, had a black spine for the first time and a very simple cover filled with a photographic artwork, overlaid with the author’s name and book’s title. The third design by Steve Kent appeared in 1985: it combined elements of the previous two by keeping the black spine and the photographic artwork, but reinstating a border on the cover and a small colour-coded system at the top of the spine. The final iteration took place in 2003: now Penguin Classics all have a black panel at the bottom with the author’s name in orange and the book’s title in white, a slim white band with the series name, and a full-bleed image in the space above.

As the list has expanded and become increasingly international, it has become more and more difficult to make a change to the cover design. Logistically it involves rejacketing a huge number of titles and coordinating new templates across all the different offices around the world, so it is certainly not a whimsical decision. If the design were to change again it would need a coordinated strategy behind it.

8. Penguin Classics is the trademark list of the publishing firm. It has existed for so many decades. Are there any titles that are perennial bestsellers or do some titles on the list exist because of their seminal value to a literary canon?

The graph of Penguin Classics sales is L-shaped: there are many titles that sell a few copies a year and a few titles that sell many copies. Some of the perennial bestsellers include Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell, Jane Eyreby Charlotte Bronte and Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen.

9. Dr Rieu’s impressive track record of selling at least a million copies a year of the 130 titles on his list would be the envy of many publishers even today. What are the combined digital and print sales figures of the Penguin Classics now? Titles on this sell better in digital or print or are the sales in equal measure?

I’m afraid I don’t have the data, but I believe print sales are still higher than digital. The early sales figures are very impressive, even for mid-20th century book sales, but these were all very impressive – much higher than figures today.

10. Has your passion for Malory’s Morte D’Arthur and the many iterations it has undergone over the centuries in any way influenced your fascination for the evolution of the Penguin Classic list & book covers?

I do love Malory’s Morte D’Arthur and the Arthurian legends. (In fact I am currently reading A Glastonbury Romance by John Cowper Powys, as I travel around India, which is intimately wrapped up with the legends of King Arthur.) Perhaps there is something quixotic about the quest to gather all the Penguin Classics into a single place. If so, I’d better be careful: we know from the legend that those who achieve the Holy Grail do not return: they’re spirited away to a different plain . . .

11. What are the decision-making elements to include a title on this list that you feel a commissioning editor working today in a firm would benefit from knowing? Would these principles of identifying a good book work across genres?

I am one of many editors of Penguin Classics around the world – and a relatively new addition to the team – so I do not have an authoritative answer, but for me, I do have a few criteria that I use for identifying a classic: it must have literary quality (i.e. it must be written well), it should be historically significant (i.e. it was a bestseller at the time, or it influenced other writers, or it changed the world in some way, or it invented a new literary form etc) and it should have an enduring reputation (i.e. it should still be read, studied or discussed somewhere in the world). Above all it must still be ‘alive’ — it needs to be able to speak to us across time and space and expand our experience of what it means to be human.

12. Do you have any back stories to share about putting this book together that made you pause and think about the resilience of this list or the vision of the founding team — Allen Lane and Dr Rieu?

Allen Lane liked the Penguin logo because he thought it had ‘a certain dignified flippancy’ and I think that combination of serious good humour pervades the Classics list to this day. It is very moving to read E. V. Rieu’s retirement speech, when he stepped down from running the list in 1964. At one point he admits that he had initially been uncertain whether Goncharov had written Oblomov or vice versa. ‘Now, of course, I know that Oblomov was the author,’ he quipped. ‘Or am I wrong?’ And he finishes his speech with some inspiring words: ‘The Penguin Classics, though I designed them to give pleasure even more than instruction, have been hailed as the greatest educative force of the twentieth century. And far be it for me to quarrel with that encomium, for there is no one whom they have educated more than myself.’

26 November 2018

essential task of being a rich historical documentation of a sterling list while being a repository of world literature translated in to English. Henry Eliot’s comments in the book about Dr Rieu’s vision and his intention of housing only the well-known texts as translations on this list is a good reference point for many of the ongoing discussions in the literary world about translations. In fact Dr Rieu’s classic translation of Homer’s The Odyssey has been prescribed for decades by universities around the world. Dr. Rieu favoured prose but this was (thankfully!) reviewed by his successor, Betty Radice. While reading The Penguin Classics Book I came across a fabulous discussion between Dr E.V. Rieu and Rev. J. B. Phillips on

essential task of being a rich historical documentation of a sterling list while being a repository of world literature translated in to English. Henry Eliot’s comments in the book about Dr Rieu’s vision and his intention of housing only the well-known texts as translations on this list is a good reference point for many of the ongoing discussions in the literary world about translations. In fact Dr Rieu’s classic translation of Homer’s The Odyssey has been prescribed for decades by universities around the world. Dr. Rieu favoured prose but this was (thankfully!) reviewed by his successor, Betty Radice. While reading The Penguin Classics Book I came across a fabulous discussion between Dr E.V. Rieu and Rev. J. B. Phillips on