Aleph announces children’s literature list

30 March 2022

30 March 2022

To write well you need knowledge that is specific.

(p.67 The Blue Book)

…the writer’s job is to reveal where the experiment in living goes wrong.”

(p.40 A Time Outside this Time)

It is a privilege to be able to read a writer’s journal soon after reading his latest novel. Amitava Kumar has a way with words. More than that. It is his ability to be able to pour his creative energy into whatever he is writing; it could be a social media post or an essay or a novel. Every piece of writing seems to be written with equal thought and care. This holds true of his latest offerings. Published a few months apart in India, by two different publishers — Aleph and HarperCollins India.

The Blue Book: A Writer’s Journal has a slow, meandering feel to it. The writer takes the reader through a lovely amble of his musings on writings, his encounters with other writers, the discipline it requires to write, and nuggets of wisdom that other writers may have shared with Amitava Kumar. The book is beautifully illustrated by his watercolour paintings — an art form that he took up during the pandemic. The paintings are vibrant, pure, and he uses bright colours. Curiously, he is constantly experimenting, so there is no fixed style to his compositions. It is impossible to gauge what will come next. But it is the specifics in the painting, whether the detail of a tulip flower or the painting across a newspaper that shows young girls celebrating Holi just above a photograph of the poet, Mahadevi Verma that make Amitava Kumar’s creations all the more interesting. It is his ability to make the reader share immediately his perspective. His way of seeing. Whether the reader has to agree or not is an entirely different matter. But at least the artist has been persuasive enough to highlight his viewpoint. But The Blue Book is also a pandemic journal. Irrespective of all the name dropping and truly wise advice that he shares, it is the astonishing discipline, clarity and peace that is exuded through the book which shines through. It is the gift of time that this wretched pandemic has given to many individuals. It is possible to channel one’s energies into an activity, discover new talents and blossom.

A Time Outside This Time could not be further from the calm The Blue Book exudes. The novel is scattered. Its structure mimics the shattering experience it is to live in this world of fake news and post-truth. Amitava Kumar opts to tell a few stories, blurring the lines between fact and fiction. It is at times hard to tell if the narrator Satya is Amitava or just Satya. Sometimes it is impossible to tell if this is fiction or a diary of events. It is almost as if it is left to the reader to piece together the narrative and make sense of it. The stories that exist are fine by themselves but interspersing them with Satya’s childhood memories of communal violence or of his adulthood, his marriage, his wife Vaani’s conversations makes it dizzying to read. Apparently, this book is an attempt by Amitava Kumar to write in fiction the challenges caused by fake news and truth. It is unclear whether this is meant to be reportage or a novel. At the best of times, a good writer is deeply dependent upon real experiences. It is the author’s craftsmanship that presents the world to the reader through the prism of fiction. Whereas in A Time Outside This Time the preoccupation of the writer to discuss this new post-truth world where fake news dominates is not very convincing since it is the role of the writer to use art to present reality. Isn’t that a form of artifice, fake news if you will? So how does one read A Time Outside This Time? It is not easy to say.

17 Feb 2022

The Book of Indian Dogs by well-known naturalist and conservationist Theodore Bhaskaran is a testimony to the importance of preserving Indian breeds. Apparently in the eighteenth century a Frenchman travelling around the country recorded more than fifty distinct breeds. But now only a handful survive — Bakharwal, Himalayan mastiffs, Himalayan sheepdog, Jonangi, Kombai, Koochee, Sindhi, Pandikona, Patti, Lhasa Apso, Tibetan spaniel, Tibetan terrier, Alaknoori, Banjara, Caravan hounds, Chippiparais, Kaikadi, Kanni, Kurumalai, Mudhol, Pashmis, Rajapalayams, Rampur hounds and Vaghari hounds.

In The Book of Indian Dogs the author builds upon his vast experience as a dog-lover, owner, naturalist, conservationist and an active member of the Kennel Club of India ( KCI) to focus on the importance of preserving these indigenous breeds. These require active patronage from governments and individuals if these species have to survive. A major reason for their disappearance from public view is attributed to the import of breeds by the British during colonial rule and the subsequent apathy by successive governements in independent India. Apparently there have been attempts to revive indigenous breeds. For instance in 1981 at the Kolhapur Canine Dog show forty Caravan hounds were shown. By 1984 standards were established and at least ten breeds — including the Rampur hounds, Caravan hound, Rajapalayam and Himalayan mastiff — were accorded recognition in the country. And yet as late as 2014 the KCI had not as yet accepted the Jonangi, one of the pristine indigenous breeds, to be recognised. The challenges in according to recognition to Indian breeds exists despite it being proven as happened during the IPKF operations in Sri Lanka ( 1987-1990) when the dogs contracted tick fever leading to anaemia and needed transfusions that the Chippiparai dogs are safe and universal donors. A good way of preserving Indian breeds ( that are also considered to be a distant relative of the Australian dingoes) is by introducing them in the canine breeding programmes of the Indian Army. For now the two breeding centres managed by the Indian Army at Meerut and Tekanpur focus primarily on Alsatians and Labradors. The lineage of these dogs can still be traced back to families in Europe. As for their health management — it is another big challenge.

While reading the book I was reminded of some of the dogs we have had in the family. One of them was Jasper — a mix between a Tibetan mastiff and a cocker spaniel. He had a foul temper ( attributed to the mastiff blood) but was utterly indulgent and adorable towards my brother and I. We loved him dearly. Another one was the extraordinarily beautiful grey alsation Pasha. He had the most magnificent cowl. But it was with his arrival in the family that my grandparents bought their first desert cooler in 1970. Then we received a couple of narcotic sniffer dogs who had been trained at Tekanpur. They were siblings — Shiva and Sangha— named by their vets. Stupendous examples of yellow labradors whose lineage could be traced to Germany. Their grandparents had been brought to India by the vets at Tekanpur for the breeding programme. Though the sniffer did some tremendous work with the department they were attached to they were delicate creatures and needed a lot of caregiving. My father has also owned dogs brought in from the Meerut RVC particularly gun shy dogs who were being disposed off. Now my parents own desi dogs picked up off the streets apart from the many they look after in their colony. The foreign breeds have required a lot of care but remarkably enough one of the desis living at home — Chhoti — requires intensive caregiving and is a very delicate dog.

Theodore Bhaskaran’s well documented and passionate account of desi dogs is probably the first of its kind in the country. It gives a bird’s-eye view of the importance dogs have played in history to present times. Despite there being reservations about dogs amongst many Indians and that every half hour a person succumbs to rabies in India there is a great demand for dogs to be kept as pets. If these expectations are managed by introducing indigenous breeds it may help in their preservation.

The publishers Aleph too need to be commended for creating a niche and well-curated list of nature writings. These document as well as focus with urgency upon the work required to preserve different species. The Book of Indian Dogs is an essential part of this seminal list.

S. Theodore Bhaskaran The Book of Indian Dogs Aleph Book Company, New Delhi, 2017. Hb. pp. 120 Rs. 399

On 20 December 2013, at its 68th session, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) decided to proclaim 3 March, the day of the adoption of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), as World Wildlife Day. In its resolution,[2] the General Assembly reaffirmed the intrinsic value of wildlife and its various contributions, including ecological, genetic, social, economic, scientific, educational, cultural, recreational and aesthetic, to sustainable development and human well-being.

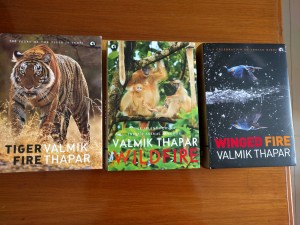

To commemorate this day, I am posting pictures of some of the wildlife books that I  have enjoyed. The absolutely scrumptious trilogy published by renowned wildlife conservationist Valmik Thapar lead the list. The books are– Tiger Fire, Wild Fire and Winged Fire. These are a “must have” not only for the stupendous production, quality of photographs but also for the amount of research that has been presented. It is probably the first time such an ambitious task has been undertaken in India wherein an extensive selection of historical accounts in writing and paintings, brilliant photographs with never before seen images of wildlife ( much like the pioneering work done by Jacques Cousteau’s photo-documentation of ocean life) and an overview of the conservation efforts made by governments with an informed and critical understanding by Valmik Thapar.

have enjoyed. The absolutely scrumptious trilogy published by renowned wildlife conservationist Valmik Thapar lead the list. The books are– Tiger Fire, Wild Fire and Winged Fire. These are a “must have” not only for the stupendous production, quality of photographs but also for the amount of research that has been presented. It is probably the first time such an ambitious task has been undertaken in India wherein an extensive selection of historical accounts in writing and paintings, brilliant photographs with never before seen images of wildlife ( much like the pioneering work done by Jacques Cousteau’s photo-documentation of ocean life) and an overview of the conservation efforts made by governments with an informed and critical understanding by Valmik Thapar.

Speaking Tiger too has republished a couple of books by Jim Corbett.

Last year Hachette India published Vivek Menon’s  incredibly detailed guide to Indian Mammals which even game wardens consider as their Bible! A fact we discovered while on a trip to a wildlife sanctuary last year. It was being sold at the entrance of the park and the guides were encouraging the tourists to buy it for its authentic and accurate information.

incredibly detailed guide to Indian Mammals which even game wardens consider as their Bible! A fact we discovered while on a trip to a wildlife sanctuary last year. It was being sold at the entrance of the park and the guides were encouraging the tourists to buy it for its authentic and accurate information.

There are also a bunch of books for children discussing wildlife conservation by not demonising the unknown, instead respecting other species and learning to live in harmony. ( Finally!) We need many more books like these given how there are hunts organised as new tourism packages. I am posting pictures of a few examples from National Book Trust ( NBT) and Puffin but there are many more available in the market now.

3 March 2016

( Aleph sent me an advance reading copy of Saad Z. Hossain’s debut novel, Escape from Baghdad! Upon reading it, Saad and I exchanged emails furiously. Here is an extract from the correspondence, published with the author’s permission. )

I read your novel in more or less one sitting. The idea of Dagr, an ex-economics professor, and Kinza, a black marketeer, make a very odd couple. To top it when they discover they have been handed over a former aide of Saddam Hussein who persuades them with the promise of gold if they help him escape from Baghdad is downright ridiculous. But given the absurdity of war, it is a plausible plot too. Anything can happen. Escape from Baghdad! is a satirical novel that is outrageously funny in parts, disconcerting too and quite, quite bizarre. I do not know why I kept thinking of that particular episode of Alan Alda as Hawkeye Pierce and his colleagues trying to make gin in their tent while the Korean War reached a miserable crescendo around them. The micro-detailing of a few characters, inevitably male save for the chic Sabeen, is so well done. It is also so characteristic of war where there are more men to be seen, women are in the background and play a more active role at the time of post-conflict reconstruction. They do exist but not necessarily in the areas of combat. It is a rare Sabeen who ventures forth. Sure women combatants are to be seen more now in contemporary warfare, but it was probably still rare at the time of Operation Desert Storm. Yet it is as if these characters are at peace with themselves, happy to survive playing along with the evolving rules (does war have any rules?), not caring about emotions and learning to quell any sensitivity they had like Dagr remembering his wife’s hand on her deathbed.

Saad: Thanks for the kind words, and for getting through the book so fast. Aleph has been amazingly easy to work with, they are clearly good people

JBR: Why did you choose to write a novel about the Gulf War?

When I started writing this, it was before Isis, or Syria, or the Arab Spring. The Gulf War was really the big war of our times, and looking back at Iraq now, I feel that it still is. I wanted to tell a war story, and the history of Baghdad, with all the great mythology, and just the location next to the Tigris and Euphrates was really attractive. I think I started it around 2010. I wasn’t very serious about it at first. The book was first published in Dhaka in 2013 by Bengal Publications.

According to an interview you did with LARB, you never went to Baghdad, and yet this story? Why?

I wrote the story as more of a fantasy than an outright satire or war history. For me, large parts of it existed outside of time and logic. Much of it too, was set in closed spaces, like safe houses and alley ways, and this was just how it turned out. In the very first chapter I had actually envisioned a sweeping, circuitous journey from Baghdad to Mosul, but I couldn’t even get them past two neighborhoods.

But isn’t that exactly what war does to a society/civilization?

Yes, that’s why I prefer using fantasy elements/techniques to deal with war itself. The surreal quality represents also the mental state of the observer, who is himself altered by the horrible things he is experiencing. I’m also now beginning to appreciate the long term after effects of war on a population’s psyche. For example Bangladesh is still so firmly rooted in the past of our 1971 War, almost every aspect of life, including literature is somehow tied to it. The damage is not short lived.

Bangladesh fiction in English is very mature and sophisticated. Much of it is set in the country itself, focused on political violence, so why not write about Bangladesh? Not that I want to bracket you to a localised space but someone like you who obviously has such a strong and nuanced grasp of the English language could produce some fantastic literary satirical commentary on the present. In India Shovon Choudhary has produced a remarkable satirical novel — The Competent Authority, also published by Aleph.

You are right, of course, Bangladesh is ripe for satire, as are most third world countries. I’m a bit afraid because I want to do it right, and I know that if certain things don’t ring true, I’ll face a lot of criticism at home for it

Fascinating point. Now why do you feel this? Is there an example you can share?

Well just the word djinn, for example. The English word is genie. A genie is a cute girl wearing harem pants granting wishes to Larry Hagman. How can I get across the menace, the fear, the hundreds of years of dread our people have of djinns? How much space do I have to waste on paper trying to erase the bubble gum connotation of genie? Will it be successful in the end, or will the English reader just be confused? What about a word like Ravan, which has an instant connotation for us, a name like a bomb on a page, but in English, it’s just a foreign sounding word that requires a footnote, something alien that the eye just blips over. For me to convey the weight of Ravan, I’d have to build that up, to recreate the mythology for the reader, to act out everything.

Isn’t the purpose of a writer to disturb the equanimity? Will there be a second book? If so, what? Btw, have you read The Black Coat by Neamat Imam?

I haven’t read it. I just googled it, it looks good, I’m going to find a copy. There isn’t a second book, this was not designed to have a serial, the ending is left open to allow the readers to make their own judgments for the surviving characters. I am writing a second novel on Djinns, which is set in Dhaka, so I hope to address some of the issues facing us there.

The story you choose to etch is a fine line between a dystopian world and a war novel. Is that how it is meant to be?

Yes, in my mind there is not one specific reality, but rather many versions which exist at the same time, and if we consider war as a pocket reality, it would certainly reflect a very dystopian nature. While we do not live in a dystopia, there are certainly pockets of time and space in this world which very strongly resemble it.

It is particularly devastating to consider a people who believed in economics, and GDP growth, education, houses, mortgages, retirements and pensions to suddenly be pitched into a new existence that has neither hope, nor logic, nor any use for their civilian skills.

True. I often think we are living a scifi life. It makes me wonder on what is reality?

My understanding is that the human brain uses sensory input to create a simulation of the world, which is essentially the ‘reality’ we are carrying around in our minds. This is a formidable tool since it allows us to analyze situations, recall and recalibrate the model, and even to run mental games to predict the outcome of various actions. For a hunter gatherer, the brain must have been an extremely powerful tool, like having a computer in the Stone Age. But at the same time, because these mental simulations are just approximations of what is actually there I can see that reality for everyone can be subtly different, and if we stretch that a little bit, it makes sense that many different worlds exist in this one.

The Indian subcontinent is a hotbed for political nationalism and neverending skirmishes, with peace not in sight. Living in Dhaka and writing this novel at the back of car while commuting in the hellish traffic Escape from Baghdad! seems like a strong indictment of war but also builds a case for pacifism. Was that intentional?

War is a complex thing. It’s easy to say that we are anti-war, and for the most part, who would actually be pro-war? I mean what lunatic would give up the normalcy of their existence to go and bleed and die in the mud? Even for wars of aggression, the math often doesn’t work out: the cost of conquering and pacifying another country isn’t worth the consequences of doing so. Yet, for all that, war has been a constant companion of humanity from ancient times. It is, I think, tied into our pack animal mentality. The very quality which allows us to freely collaborate, to collectively build large projects, is the same thing which leads to organized violence as a response to certain trigger situations. I believe that the causes of wars have all been minutely parsed and analyzed, broken down into the actions and motivations of different pressure groups, but all of this still does not explain the reality of battalions of ordinary people willing to strap on swords and guns and armor and commit to slaughtering each other. That willingness is a psychological problem for the entire human race to contend with, I think.

JB: As long as you raise questions or leave situations ambiguous, forcing readers to ask questions about war, the novel will survive for a long time.

The creation of old women especially Mother Davala are very reminiscent of those found in mythology across the world. It is an interesting literary technique to introduce in a war novel.

Mother Davala is one of the three furies of Greek myth, the fates whom even the Gods are afraid of. They are also in charge of retribution, which was apt for this particular scenario. This was one of the things I was talking about earlier, with the mythology built into the language. The Furies have such a resonance in English, such a long history in literature, that they carry a hefty weight. I could have used, instead, someone like Inanna, the Sumerian goddess of love and conflict, but that name has no real oomph in English, and so it would be a wasted reference.

So if you find it challenging to work mythological elements from other cultures into your fiction, how were The Furies easy to work with?

I think the challenge is to use non English mythology while writing in English. English mythology kind of covers Norse, Greek, Arthurian, as well as Christian mythology, of course. To use elements of any of those is very easy because there is a lot of precedent, and the words already exist in the lexicon. The problem arises when you are writing in English about a non western culture. Then you are forced to describe gods, goddesses, demons, etc, which sound childish and irrational, because they have no linguistic resonance in English. If I say the words Christ and crucifixion, there is an instant emotional response from the reader. If I describe the story of the falcon god Horus who was born in a strange way from his mother Osiris, and performed magical acts in the desert and then eventually died and returned to life, it just sounds quaint, and peculiar.

Have you written fiction before this novel?

I’ve been writing for a long time, since I was in middle school, and my earlier efforts have produced a vast quantity of bad science fiction and fantasy. It started with a bunch of friends trying to collaborate on a story for some class. We each picked a character, and made a race, history, etc for them. The idea was to create a kind of mainstream fantasy story. I remember we all used to read a lot of David Eddings back then. The others all dropped out, but I just kept going. Writing a lot of bad genre fiction helps you though, because you lose the fear of finishing things, plus all that writing actually hones your skills.

How long did it take you to write this story and how did you get a publication deal? Was it an uphill task as is often made out to be?

I took a couple of years to write this. It started when I joined a writers group, and I had to submit something. That was when I wrote the first chapter. The group was very serious and we had strict deadlines, so I just kept writing the story to appease them, and then I was ten chapters in and growing attached to the characters, so I decided to go ahead and finish it. This was a group in Dhaka, it was offline, we used to physically meet and critique stuff. A lot of good work was published out of that. It’s definitely one of the critical things an author needs.

Publishing seemed impossibly daunting at first, but when it happened, it was easy, and through word of mouth. I knew my publisher in Bangladesh, and when they started a new English imprint, they were looking for new titles, and I was selected. Some of my friends knew the US publisher, Unnamed Press, and I got introduced, they liked it, and decided to print. Aleph, too, happened similarly. You can spend years querying and filling up random people’s slush piles, and sometimes things just happen without effort. My philosophy is that I am writing for myself, with a readership of half a dozen people in mind, and I am happy if I can improve my craft and produce something clever. The subsequent success or failure of it isn’t something I can necessarily control.

Saad Z Hossain Escape from Baghdad! Aleph Book Company, New Delhi, 2015. Pb. pp 286. Rs. 399

28 August 2015

Madras and Chennai came into existence almost simultaneously in 1639, as two contiguous areas. While Madras went on to lend its name to the larger southern peninsula or Madras Presidency, it also absorbed Chennai into its fold as it grew. Debate over the origins of the words Madras and Chennai continues long after the Tamil Nadu government’s decision in 1996 to officially change the capital city’s name.

Madras and Chennai came into existence almost simultaneously in 1639, as two contiguous areas. While Madras went on to lend its name to the larger southern peninsula or Madras Presidency, it also absorbed Chennai into its fold as it grew. Debate over the origins of the words Madras and Chennai continues long after the Tamil Nadu government’s decision in 1996 to officially change the capital city’s name.

Madras, Chennai and the Self: Conversations with the city by Tulsi Badrinath was commissioned to commemorate Chennai’s 375th birthday. The twelve people she chose to profile lived in different parts of the city. Each chapter is delightful, since it immerses you in the city — sharing her thoughts, reflections, observations and being alive to the sensuous experience. Every single person profiled is done very well, with the author allowing the personality of the subject to shine through. Two of the profiles really stayed with me after I had read the book — M Krishnan, naturalist and Kiruba Shankar, digital evangelist. Without being overly inquisitive and making the reader a voyeur in the process, Tulsi Badrinath balances her profiles of individuals by giving select insights into this character, personality and life, not necessarily compromising their privacy. For instance, M Krishnan cooking as his wife did not particularly care for it or Kiruba Shankar recounting how he came to be a digital expert and a farmer as he is known today. If publishers shared their material then the chapter by Tulsi Badrinath on M Krishnan could be included in a revised edition of Aleph’s Of Birds and Birdsong, a selection of writings by the naturalist–it would add immensely to it.

The last book on Chennai which was super was by Nirmala Lakshman, Degree Coffee by the Yard, an insider’s account of the city. Tulsi Badrinath’s book is a good companion to it. It is immensely likeable.

Tulsi Badrinath Madras, Chennai and the Self: Conversations with the City Pan Macmillan India, New Delhi, 2015. Pb. pp. 230.

30 March 2015

( While reading ManBooker shortlisted novel, Neel Mukherjee’s The Lives of Others, I began to discuss it with Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar. He is an avid reader. Initially he was happy with the novel, it was well written, but then there was this long silence from him. A few days ago, I got a message from him at 2am to say he was not very comfortable at the portrayal of Santhals in the book. He should know. It is his community. So I asked him to contribute a guest post for my blog. I am posting it as he sent it. )

When I first saw the Indian hardcover edition of Neel Mukherjee’s second novel, The Lives of Others, at a book store in Kolkata in June 2014, I was struck by the familiarity of the contents of the book. Having grown up and lived all my life in a southern corner of the state of Jharkhand, the complexities of a Bengali joint family and the Naxalite movement were familiar issues. However, what was even more familiar – and striking – was the map at the beginning of the novel; for inset in that map were all the places that remind me of home. They are not big or famous places. They are small, district towns and villages. They do not find a regular mention in the media like bigger cities like Kolkata or Delhi do. An incident that takes place in these places has to be very big, remarkable in every way to have people talk about these places. Even if these places find a mention in the front pages of The Telegraph or The Statesman, I am quite sure that many readers won’t remember their names just a mere 24 hours after having read about them. Yet, these are the places whose names I have been hearing ever since I developed the ability to listen to and understand words and names; maybe, since when I was 2 or 3 years old. I am 31 now, and the names of these places fill me with a desire to just run back to my ancestral village or my hometown at the first given opportunity.

I can vouch for the actuality of three places in that inset: Belpahari, Binpur, and Jhargram. I am not too sure of Gidighati and Majgeria. Perhaps, they, too, are real. Perhaps, they are a creation of the author’s imagination. But Belpahari, Binpur and Jhargram are real. They exist. There is another place mentioned a number of times in the novel, giving that place a certain importance, although it does not appear in the map: Gidhni.

The name of my village is Kishoripur. It is the village of my ancestors; the place where my father, grandfather, and all those who came before were born and raised. Kishoripur is a village in Chakulia block of East Singbhum district of Jharkhand, a mere 10 km from the border with West Bengal. Both Gidhni and Belpahari are some 10-15 km from Kishoripur, in two different directions—Gidhni, towards the east; Belpahari, towards the north. Jhargram is some 30-35 km from Kishoripur, towards the east. Binpur is some 20-25 km from Kishoripur, towards the north-east. I remember a saying I have grown up with. Choluk gaadi Belpahari—Let the vehicle go to Belpahari. This is a cry of excitement that village people, who, in earlier times, didn’t usually get to see a car or bus or other automobile, used to make when they boarded a gaadi. The poetry in this simple cry of excitement cannot be missed. Gaadi and Belpahari rhyme with one another. Somewhere in the book, Ghatshila has been mentioned. Ghatshila, the place famous for its copper factory, and for being a favourite weekend getaway among the Bengalis from Kolkata, is the place where my parents used to work and where I have grown up. Ghatshila is my hometown. Belpahari, Binpur, and Jhargram were the reasons that drew me – and, ultimately, made me read – The Lives of Others; while Gidhni and Ghatshila filled me with a feeling of pride that the places I am so familiar with – one of those being my hometown, no less – are being read about by people all over the world.

As I progressed with the novel and the ups and downs in the Ghoshes’ lives, I came across many other familiar places, like, Bali, Nalhati, and Memari. I am working with the government of Jharkhand and am posted in Pakur. Pakur is a district in the Santhal Pargana division of Jharkhand. When I came to join my job in Pakur, I had no idea about the route. So my father accompanied me and we came from Ghatshila to Pakur by road. We passed through four districts in West Bengal – Pashchim Medinipur (western Medinipur, mentioned in the book), Bankura, Bardhaman, and Birbhum – before we entered Jharkhand again and reached Pakur. Nalhati and Memari were two places we passed through. Now, I travel from Ghatshila to Pakur by train. I first travel from Ghatshila to Howrah, from where I catch the train to Pakur. Bali and Nalhati are two stations I pass through. The familiarity provided by these places further drew me into The Lives of Others. I wasn’t reading the book because I wanted to know what happened with the Ghoshes. I was reading The Lives of Others because it was so familiar, because it told me things I knew, because I hoped to find another familiar point in one of its pages, because it seemed to speak to me.

I wasn’t disappointed. The book threw up the names of other familiar places. Jamshedpur, Giridih, Latehar, Chhipodohar, McCluskieganj. I had goose flesh as I read the names of these places and realised that many like me, all over the world, were reading these names.

Not only places, The Lives of Others was familiar also with regards certain terms that I have grown up with. For example, munish. Our family owns land in our village. When I was very little, my grandfather used to talk about letting the munish farm our fields. At that time, I understood that munish meant workers. Men who work in the fields. As I grew up, I learnt that munish meant the sharecroppers who worked our fields for us. This, exactly, is the meaning The Lives of Others gives for the word munish.

Then there were the familiar Bengali sayings. “fourteen forefathers”. When I read this term in Chapter 18, I, despite the sad and fearful context of this chapter, couldn’t help smiling. That is because I have heard people saying the original term: Choddo gushti—and also the comic implications of this term when it is said in anger. Another saying was: “a case of the sieve saying to the colander, “Why do you have so many holes in your arse?””, in Chapter 10. I know the Bengali of this one too, although that has the sieve with a needle. The sieve is riddled with holes, but it accuses the needle of having a hole!

The Lives of Others was, indeed, speaking to me. I don’t think I need to write about how meticulous this book is. I came to know of the politics in West Bengal, as well as about the processes involved in the manufacture of paper—this shows how good the research, the work on the background, has been. Finally, when the narrative reached the villages of West Medinipur, and Santhal characters entered the story, I found myself turning the pages in sheer delight. I wanted to read what had been written about Santhals, how they had been presented.

And this undid everything.

Maybe I had had too high expectations of The Lives of Others. Just because a book seemed so familiar, and was well-researched and well-written, I had felt that it would be entirely satisfactory. I was wrong. The description of the Santhals in The Lives of Others is anything but satisfactory. At the most, it is stereotypical, one dimensional, and whatever the author has written about Santhals has been drawn so heavily from whatever opinion the world, in general, holds about Santhals – about the Adivasis, in fact – that it all seems like a cliché.

First, there is this violent scene in Chapter 10—a moneylender called Senapati Nayek being hacked to death with tangi (an axe). The men who wielded the tangis were Dhiren, a young man from Kolkata who has turned to Naxalism, and Shankar Soren, a Santhal man from the village Majgeria. Senapati Nayek was hacked twice, and it has not been mentioned who hacked him, whether Dhiren or Shankar. It could be that each of them hacked him once. It could also be that either Dhiren or Shankar hacked him twice. In Dhiren’s case, it could be understood that he was driven by his Naxalite ideal to kill the landlord. He had something to prove. In Shankar’s case, he only had his poverty, and the fact that Senapati Nayek was cheating him out of what he produced on his land. The novel tells us that Senapati Nayek cheated Shankar Soren, that Shankar Soren sought revenge. The novel does not tell us what kind of person Shankar Soren was. He could have been a good man, but he could have also been a bad, a cruel man. For, the novel tells us that he beat his wife. He beat his wife, the novel informs us, out of frustration, but that could also mean that Shankar was depressed, that there was something going on in his mind. The novel further tells us that Shankar was drawn by Dhiren into the plot to kill Senapati. Shankar agrees to it. But, sadly, whatever the novel tells us about Shankar, it does not give us a detailed insight into his back story, it does not give Shankar a redeeming story. Shankar, here, represents the Santhals, and what we come to know about Santhals through the character of Shankar is that Santhals are naïve, helpless, frustrated, angry, yield easily to incitement, and violent—in this order. I don’t understand if this description of Santhals – through the character of Shankar – does any good to Santhals. Chances are that readers who are not familiar with Santhals might take Santhals to be fools who tend to lose whatever they own and repent for it, and then turn to violence to get their possessions back. Perhaps, Santhals might be seen as a bunch of psychos.

Second, there is this scene in Chapter 15, in which a drunk man called Ajit tells his friend Somnath: “…I find these tribal people really innocent and pure. Qualities we city-dwellers have lost.” Fine, this could be true. But let us consider the scene in its entirety. Ajit is drunk. How much weight do the proclamations of a drunk man hold? Next, there is one more friend, Shekhar, he too is drunk, who adds: “[The tribals] have no money, no jobs, no solid houses, yet look how happy they are. They sing, dance, laugh all the time, drink alcohol, all as if they didn’t have a single care in the world.” Now, isn’t this stereotyping? It has been taken for granted that tribals “have no money, no jobs, no solid houses”, and they “sing, dance, laugh all the time, drink alcohol”. Even if it is assumed that it is the voice of that particular character – and not the voice of the author who wrote this book – what positive thing do these lines hold for tribals? A reader who does not know tribals will assume that all tribals do are “sing, dance, laugh all the time, drink alcohol”.

Third, and this really irritated me. Chapter 15, just before that drunken discussion about tribals. Somnath, who is a complete lecher, is attracted to a young Santhal woman and goes to ask her the name of the flower she has put in her hair. The woman behaves coquettishly, and asks Somnath: “Babu, you give me money if I tell you the name of the flower?” At this point, I can’t help noticing, The Lives of Others turns into Satyajit Ray’s film adaptation of Sunil Gangopadhyay’s novel, Aranyer Din Ratri. The young Santhal woman could very well be Duli, the Santhal woman in the film Aranyer Din Ratri, played by Simi Garewal; while Somnath of The Lives of Others could be the city-bred Hari, played by Samit Bhanja in the film Aranyer Din Ratri. In fact, there is a scene in Aranyer Din Ratri, set in a small rural joint selling hooch, in which a drunk Duli comes to a drunk Hari and asks him to give her money to buy more hooch. “E babu, de na. Paisa de na”—Duli’s lines from the film are still clear in my mind, not because I liked those lines, but because, being a Santhal, I found those lines terribly embarrassing, and the character of Duli – played by Simi Garewal – absolutely unreal and a caricature. The same feeling of embarrassment came over me when I read about the Santhal woman in The Lives of Others asking for money from a city-bred man. Simi Garewal in Aranyer Din Ratri might have looked very glamorous to some people, but I cannot forgive Satyajit Ray for making a complete hash of a Santhal character. Similarly, I cannot forgive Neel Mukherjee for Aranyer Din Ratri-fication – or Simi Garewal-isation – of a Santhal woman in his novel.

Further, in the same chapter, Somnath has successfully seduced that Santhal woman, promising to buy her liquor, and was leading her towards the forest to, apparently, make out with her. This is what has been written in the novel: “He had heard that these promiscuous tribal women had insatiable desires; they were at it all the time, with whoever approached them”. Promiscuous? I wonder if the author was trying to count the qualities of tribal women or just generalizing things. If a woman drinks alcohol, does that make her promiscuous? Was it necessary to portray “tribal women” as “promiscuous” and with “insatiable desires”? This, together with lines like, “You think we didn’t see you unable to take your eyes off the ripe tits of these Santhal women?”, “Ufff, those tits! You’re absolutely correct, Somu, they’re exactly like ripe fruit. The only thing you want to do when you see them is pluck and shove into your mouth”, and “[Santhal women] fill every single sense. But not only tits, have you noticed their waists? The way they wind that cloth around themselves, it hardly covers anything, leaves nothing really to imagination. High-blood-pressure stuff” (all lines from Chapter 15) seem to only further the Simi Garewal-isation of Santhal women. Santhal women have been presented as objects of fantasy, what spoilt, city-bred men desire. While there might be some truth in men lusting after Santhal women, is it that difficult to accept Santhal women as real persons and not merely as objects lustful men fantasize about?

Finally, in Chapter 3, there is a mention of “the burial grounds of the Santhals”. I wonder, what burial grounds? I am a Santhal. I know that we Santhals do not bury our dead. We cremate them. So where did these “burial grounds of the Santhals” come from?

The “burial grounds of the Santhals” part did put me off a bit. But it was still quite early in the novel, and I was ready to overlook this error because I had started falling in love with this novel. I found one more error: “Gidhni Junction”, in Chapter 2. Gidhni is an actual place, and the railway station at Gidhni is not a junction. If one travels to Gidhni from Howrah, one would reach Jhargram first and then Gidhni. So why would “the railtrack [become] a loop-line” and why would “the train [leave] the main railway line and [go] over the cutting”? If one travelling from Howrah needed to get down at Jhargram, he could easily get down at Jhargram without needing to travel all the way to Gidhni. I overlooked “Gidhni Junction”, initially, thinking it to be a creative freedom the author took. The type of creative freedom that Jhumpa Lahiri took in The Namesake when she made the young Ashoke Ganguly travel from Howrah to Tatanagar in an overnight train instead of in one of the many trains that ran during the daytime so that the overnight train could have an accident near Dhalbhumgarh and Ashoke Ganguly’s life be changed forever. I tried overlooking both “Gidhni Junction” and “the burial grounds of the Santhals”. But what else was written about Santhals crushed all my hopes in such a way that The Lives of Others, a book I had found so familiar, stopped working for me.

I am happy that a novel which has a few Santhal characters is being received so well all over the world; but that is exactly what makes me afraid—that readers all over the world are reading about Santhals in The Lives of Others. Some readers might even believe in what The Lives of Others tells them about Santhals, and this does not make me happy at all, because the actual lives of the Santhals is somewhat different from what The Lives of Others tells us.

25 September 2014

Neel Mukherjee The Lives of Others Random House India, London, 2014. Hb. pp. 514 Rs. 399

HANSDA SOWVENDRA SHEKHAR is the author of the novel, The Mysterious Ailment of Rupi Baskey, published by Aleph Book Company. He is a Santhal, a native of Ghatsila subdivision of Jharkhand; and he is currently living in Pakur in the Santhal Pargana division of Jharkhand, where he is working as a medical officer with the government of Jharkhand. ( http://www.alephbookcompany.com/hansda-sowvendra-shekhar )