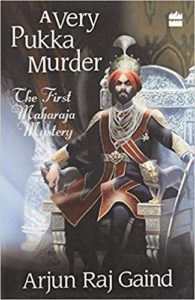

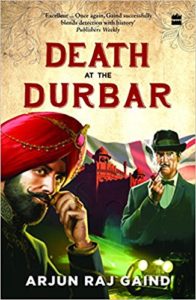

An interview with Arjun Raj Gaind, author of “The Maharaja Mysteries” — A Very Pukka Murder and Death At The Durbar. Two delightful books, set during the British Raj, charmingly written much in the vein of an Agatha Christie story, and partly inspired by the author’s grandfather. Incredible amounts of research done to get the period details accurate and it is evident. Recently these stories were sold to a television network for adaptation to the small screen.

Read on for the interview.

******

Arjun Raj Gaind is the author of the critically acclaimed historical mystery series, The Maharaja Mysteries, which are set against the picturesque backdrop of princely India during the heyday of the British Raj. Two installments have been released so far, A Very Pukka Murder (2016) and Death at the Durbar (2018). The third book in the series, The Missing Memsahib, is due for release early in 2019 by Harper Collins India and Poisoned Pen Press USA. He is also the creator and author of several comic books and graphic novels, including Empire of Blood, Project: Kalki, Reincarnation Man, The Mighty Yeti, Blade of the Warrior, and A Brief History of Death.

Here are excerpts of an interview conducted via email:

Why did you decide to write mystery stories after having been a graphic novelist?

I believe stories are universal, and that if a writer is a natural storyteller, they will refuse to allow themselves to be limited by genre or format. Ultimately, it is all about  telling stories in an original and effective manner so that your readers keep wanting to turn to the next page. Everything else, it is just filler.

telling stories in an original and effective manner so that your readers keep wanting to turn to the next page. Everything else, it is just filler.

I have always been a keen aficionado of Golden Age detective fiction, and find the manners and mystique of classical mystery very enticing. It is really quite sad that in India, we don’t really have a culture and tradition of mystery fiction. I wanted to change that, to try and create an original Indian detective, someone with the savoir-faire of James Bond but also the deductive temperament of Hercule Poirot.

Maharaja Sikander Singh actually came to me as an epiphany while I was reading William Dalrymple’s White Mughals and I found myself thinking, “Wouldn’t it be great if we had an Indian King who had fantastic adventures during the British Raj?” After that, I had no choice. I owed it to Sikander to bring him to life because as any writer will tell you, some characters are just too good to neglect.

Interestingly, he isn’t entirely fictional, but rather a composite of several real historical figures, based in part on Jagatjit Singh of Kapurthala and partially on Bhupinder Singh of Patiala, both gentlemen of monumental appetites who lived very picturesque lives. My favourite character in the series however, is the Maharaja’s manservant and sidekick, Charan Singh. He is named for and modelled after my grandfather, who I believe epitomized everything admirable about being Sikh, from unswerving loyalty to a fierce sense of duty and honour that cannot be bought or sold, no matter what the price.

Why select the British Raj as the setting for your mysteries?

I am rather an inveterate brown sahib, and have always been very fascinated by the Raj, ever since my time at the Lawrence School, Sanawar. I think that in many ways, many facets of contemporary India, whether social, economic or political, have been defined by the clash of cultures that took place between East and West during the Colonial Era. Being Punjabi and an English speaker, it is impossible to deny what a pervasive and lasting impact Imperialism has had on our lives.

At the same time, I wanted to create an original character who could hold up a mirror to the innate racism of British India. Most Indians represented in colonial fiction are shown as subservients, as outsiders, but Maharaja Sikander Singh is very different. His wealth and rank allow him access to the highest echelons of British India, and is in many ways, he is the perfect foil to illustrate the hypocrisy of English India, better educated than most of the sahibs he encounters and far more worldly, but still doomed to be a second class citizen, restricted by his race and skin colour. That is what excited me, the notion of subverting the Raj, and revisiting it, only this time from the point of view of an educated, upper class Indian, rather than a servant or a serf.

Who are the crime writers you admire?

More than writers per se, I have a bunch of favourite books and series. Evil under the Sun by Agatha Christie. Strangers on a Train and The Talented Mr. Ripley by Patricia Highsmith. The Saint books by Leslie Charteris. The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco. Simenon’s Maigret series. Ernest Bramah’s Max Carrados books. The Lord Peter Wimsey series by Dorothy L. Sayers. Inspectors Morse, Lynley and Alleyn. Nero Wolfe. The Thin Man by Dashiel Hammett. The Big Sleep by Philip Marlowe. Wallander. My name is Red. The Rose of Tibet. The Shadow of the Wind. Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil. James Ellroy’s L.A. Quartet. Satyajit Ray’s Feluda books. The Keeper of Lost Causes by Jussi Adler-Olson. The Harry Hole books by Jo Nesbo. The list is quite endless.

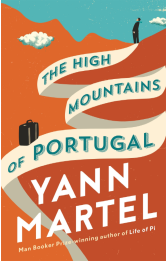

Amongst historical mystery novelists, I am a fan of the Falco series by Lindsay Davis, Steven Saylor’s Roma sub Rosa cycle, C.J Sansom’s Shardlake books, Caleb Carr’s Alienist series, Barbara Cleverly’s Joe Sandilands series, and Jason Goodwin’s Yashim the Eunuch book, to name

just a few.

Do you find there is a difference in the storytelling of a graphic novel and a mystery story? To a reader it is usually only the format that differs.

Actually, I believe the basic craft involved in writing mystery fiction and creating a sequential narrative is quite similar. The elements are exactly the same – Plot, Setting, Character, Conflict and Point of View. The main challenge with writing comics is that it is a static medium, where you are limited not only by the number of words you can use on a page, but also by the fact that you cannot really show movement. Instead, you have to suggest the illusion of movement by using a montage of fixed images that manipulate the reader, trick their imagination into seeing more than what is being said.

Interestingly, that is a great lesson to use in a mystery too, where you create and sustain a sense of suspense by deliberately placing hints and clues to keep the reader inveigled. Take Noir as an example. In a graphic novel, you create a sense of unease by using shadows and angles. In a mystery novel, you use mood and description. And of course, good dialogue is good dialogue, regardless of format.

How much research — period details, historical accuracy, language — was required for each story?

I confess, I went a little crazy doing the research. That is the part of writing historical fiction I enjoy the most, the excavation and accumulation of obscure details. It is rather like voyeurism, except you are spying on the lives of long dead people. In fact, that is what excites me about history, not the broad sweep of events, but rather the minutiae which textbooks do not reveal.

I am a firm believer in using primary sources, and while researching A Very Pukka Murder, I ended up reading more than 300 books about British India. I became obsessed with getting every detail right, from which cobbler my Maharaja would have used to have his shoes custom-made, to what brand of perfume he would have chosen to import from France. Funnily enough, along the way, i have ended up becoming somewhat of an expert about several abstruse subjects, from the variations in pugree and cummerbund styles across India to early luxury cars owned by Indian Maharajas. I also took great pains to try and get the cadences of how an educated Indian in fin de siecle India would have spoken, and also the phraseologies and parlances he would have used. By and large, I think was quite successful, although my first draft, which was about six hundred pages long, gave both my

agent and my editor indigestion, I am certain.

Why are you focused on a trilogy? A character like this evolves does he not?

Frankly, I would be delighted to release a Sikander book each year for the rest of my life. I have about eleven books plotted out so far, including one set against the backdrop of the First World War, and a

grand finale set in 1947 when the English depart and India attains independence. About the trilogy, I have been fortunate that Harper Collins India and Poisoned Pen Press have shown enough faith in my work to acquire three books. Hopefully, sales permitting, they will want to publish many more, and Maharaja Sikander Singh will be here to stay for a good many years.

The stories seem to creep forward in time, at least in the time difference between A Very Pukka Murder and Death at the Durbar. If you ever had to expand these into a series would you not find the timeline challenging?

I believe I am up to the task. Besides, I like the thought of the character growing older as his readers age. It worked for Harry Potter, didn’t it?

The stories are going to be adapted for television. Will you be doing the screenplay as well?

Not for all the money in the world. I am old and seasoned enough to recognize my limitations, and I think that the adaptation, whether for film or television, would best be served by a professional

script-writer. I do however, intend to look over his or her shoulder and backseat write every single sentence, at least until the producers decide to be rid of me.

12 May 2018