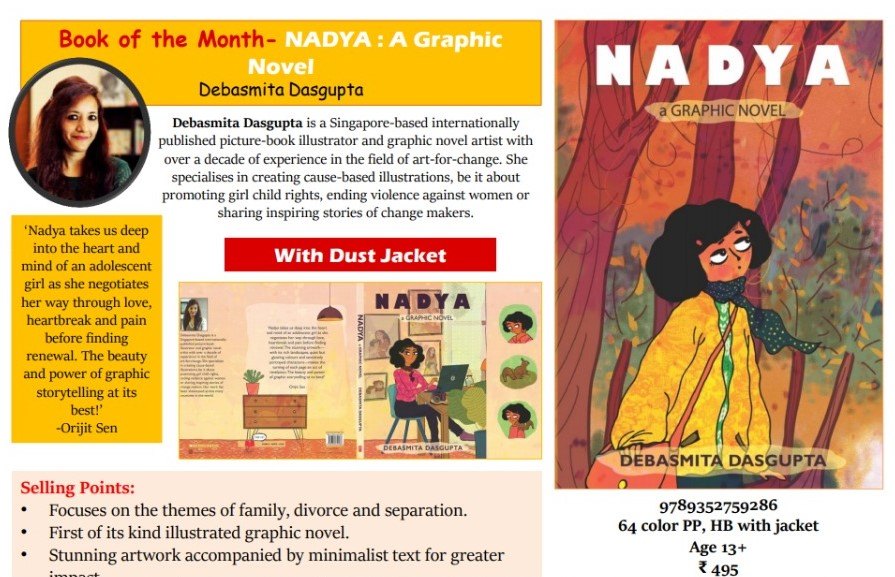

“The Windsor Knot: Her Majesty the Queen investigates” by S. J. Bennett

S. J. Bennett’s Windsor Knot ( Harper Collins India) is her first mystery novel in this newly launched series. It is also the beloved young adult author’s debut foray into adult literature. In it, she has the Queen of England, Queen Elizabeth II as an investigator. Rozie Oshodi is the Queen’s assistant private secretary who doubles up as her sidekick investigator. According to the author, “the Queen’s new Assistant Private Secretary. Rozie is a Nigerian Londoner who grew up in a council estate in Notting Hill and went on to serve in Afghanistan as a captain in the British Army. She is quick-witted, brave and somewhat amazed to find the Queen is asking her to do increasingly unusual things.” In fact, the real Queen’s current equerry is Lieutenant Colonel Nana Kofi Twumasi-Ankrah, a Ghanaian-born British army officer. Like Rozie in the book, he’s a veteran of the war in Afghanistan. S.J. Bennett adds:

I’ve always written books with a feminist element to them, and I’m fascinated by the idea of a ‘little old lady’ surrounded by men, someone who is deeply respected, but not always taken seriously. In this series, the Queen (my Queen) has learned that she can trust only certain women to keep her secrets. They are her assistant private secretaries, a role I interviewed for myself after a brief career as a strategy consultant with McKinsey. I’ll never forget walking across the forecourt of Buckingham Palace. I didn’t get that job in the end, and it’s still the one that got away.

The Windsor Knot investigates the mysterious death of a Russian on the premises of Windsor Castle. The novel is set at the time the Queen is 89 and approaching her ninetieth year. She comes across as a sparkling old lady who is very aware of the manner in which she should conduct herself as a British monarch and yet, she seems to exhibit the excitement and enthusiasm of a little school girl in getting to the truth about Maksim Brodsky, the Russian pianist. He had been invited to entertain her guests the previous night at dinner. The manner in which he is found in his room is scandalous and all attempts are made to ensure that the story is underplayed. More so, when they discover a little more about his Russian connections. Yet, those in the know, including the Queen, cannot help but speculate on the circumstances of the death. More so, since Brodsky was known to also run a political blog. So could he have possibly fallen foul of the Russian authorities, especially Putin? ( The eerie parallels of political intrigue to the ongoing story about Roman Protasevich, the Belarus blogger, are purely coincidental. Prostasevich has gone on record saying that the authorities will kill him for managing Telegram channels broadcasting mass protests against the Belarus leader, Alexander Lukashenko. )

Back to the novel. The Queen’s top policemen are investigating the crime. They are Ravi Singh, Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police; Gavin Humphreys, Director General of MI5 and the most junior of the trio, Detective Chief Inspector David Strong. They are a motley bunch who are perfect team in this mystery story. The author has everything, diversity, true representation of British society, a peep into royalty, the secret conversations, the investigation, and it is pure delight in reading excellent English, nuanced and truly Queen’s English without having to read mangled words and phrases.

I truly love how the author has set her characters in place. I can just see them develop and if she maintains the pace of creating two novels a year, she is on to an excellent formula. I hope she does not run out of ideas and plot settings. First books in a series are always dicey but S. J. Bennett is on to a good thing with this launch. It is the perfect antidote for the gloom and doom that we are surrounded by. This is just the kind of lighthearted banter, mixed with some detective work, that we as readers need to help us look the other way during theese dark pandemic days. Life goes on despite being reminded of our mortality on a daily basis.

It is the perfect blend of Wodehouse and Agatha Christie. Very English. Very much aware and happy being in the space it inhabits. And makes the best of the scenario. You don’t need to be a Royalist or an Anglophile to appreciate this kind of storytelling. Just go with it and enjoy it. The author has a very tight control on the language. She will hone her point-of-view skills fairly soon, once the characters begin to assert themselves. The first book is always a testing ground for the roles everyone will play and the author figuring out how to manipulate the scene. Soon everyone will find their niche and it will develop beautifully. I am so sure of it. This first book has sufficient glimpses of a good series in the making.

In fact, the first volume has an extract from the opening pages of the second novel in the series scheduled for publication in November 2021. It is called The Mystery of the Faberge Egg. I cannot wait to read it. Just as the webseries, The Crown, inspired this storyline, these books need to launch a webseries of their own.

On a drive one English spring evening, I found myself thinking about an episode of The Crown. The young Queen Elizabeth II had picked up a painted soldier from a model battlefield and absentmindedly returned him to the wrong place. Her punctilious private secretary corrected the mistake. And I thought to myself that, while it made a nice observation about the private secretary, it was something the Queen – the woman I knew – would never have done.

I haven’t met her, but my father has, many times. In the course of a long career in the army, he’s hosted her at the Tower of London, drunk cocktails on the Royal Yacht Britannia and been awarded medals at Buckingham Palace. The woman my father knows is funny, engaged, well-informed and good company. She would have understood that it’s impolite to fiddle with someone else’s model battlefield, and if she’d ever moved a soldier it would have been to put him in the right place, not the wrong one.

That got me thinking, here’s a woman with a lifetime of learning, who is often thought of as not very clever. But she’s recognised as a world expert on horse racing, and there are many other fields besides, such as military history, that she knows extremely well. Also, while we’re all looking at her, she’s looking out. She must spot things all the time that others don’t see.

What a perfect set-up for a detective. The woman I know could do it brilliantly.

Meanwhile, read The Windsor’s Knot — it is the perfect read.

8 June 2021