( Here are some extracts from an article published in the IIC Quarterly. It is based on a talk delivered by Dom Moraes at the Centre on April 17, 1976. )

( Here are some extracts from an article published in the IIC Quarterly. It is based on a talk delivered by Dom Moraes at the Centre on April 17, 1976. )

I recently met an exceptionally interesting man. He told me that he was a historian, and that he had a theory. According to the Hindu scriptures, he said, ancient India was full of winged machines in which the gods flew from place to place, showering the earth with blessings as they passed over it : I suppose this was the Vedic equivalent of a Presidential plane. Anyway, my historian said, as the gods flew around, paying state visits, they acquired a lot of knowledge from other countries, though I personally would have thought that if they were gods, they already knew it all. However, I do not want to be too carping a critic. My friend then told me that amidst the other titbits of information brought home in these divine aeroplanes was an English grammar. He was very serious about it. He said that that was the reason Indians today spoke such excellent English : they had been speaking it since the days of the Mahabharata. I would acccept this more readily if it were not a fact that in the days of Mahabharata, English as we know it did not exist. No. I think we must accept, however reluctantly, that English first came to India with the British.

…

What we must come to now is the fact that all colonial literature, written in the language of the colonist, is bound to be provincial. A kind of Indian literature in English started at the same time as a kind of literature started in the other colonies of Australia and Canada. It cannot be said that the literature produced by any of these three colonies was any better or any worse than the literature produced by others. Indeed, they all resemble each other to some extent. One of the facts about colonies, especially in the days when ship under sail from England to the outposts of Empire were, considered the quickest and most reliable carriers of news and mails—there was no alternative but pigeons—was that the colony was always some weeks or months behind the mother country in the receipt of pure news. This being the case, the colony was usually some years behind the mother country in the receipt of new literature. The lonely writers of Australia and Canada, and therefore of India, for those who chose to write in English, were always some years behind contemporary literary movements in England.

…

In the 1930s three Indian novelists, all of whom are still alive, emerged. These were Mulk Raj Anand, R. K. Narayan, and Raja Rao. Mulk Raj Anand is an old and dear friend of mine, yet to much of his writing, as writ ing in English, Yeat’s criticism applies. He writes as though he was trans lating from his native Punjabi into English, hence the recurrent phrases in his work which may sound ridiculous to the reader—for example—”He waved his head in silent assent,” or “O thou raper of thy mother ! Thou raper of thy sister !” Anand started to write his novels at a time when the English book market was (a) empty of exotica and (b) when the intellectuals in England were mainly leftists. He wrote of India, which made him exotic, especially since, unlike Kipling, still alive then, he was an Indian. He wrote of the deprived and poor from a Marxist standpoint, which made him popu lar with the intellectuals. But his work still demands respect, especially his latest work. R. K. Narayan was a very different figure. While Anand lived in England, Narayan never strayed far from his own Mysore. While Anand never seemed to have taken breath in pouring out his sentences, Narayan was a very careful novelist, with a perfect sense of time and place. The town he created, Malgudi, has a truth of its own, drawn from observation and sympathy. Narayan had no political bias, but an intense awareness of people and a sense of sympathy with their predicaments. Anand wrote of huge pre dicaments, Narayan of small ones. But a lot of novelists, like Forster—and Narayan is a sort of Indian Forster, dryly witty, though never cynical, always watchful, and able to construct wordlessly upon his words—have described huge events through small ones. Narayan is incidentally the first Indian writer in English to have shown himself to be a rider of that strange beast, a sense of humour. Mr. Khushwant Singh, the other day, described Narayan’s style as “too simple”. I think his style is very complex. Anyone who is able to be simple is far more likely to be complex than a person who is striving to be complex in thought and style. This is my main criticism of Raja Rao, and perhaps this is why I find his books utterly unreadable. But an interesting common denominator between these three writers is that all of them achieved some reputation abroad, and that until they had achieved this reputation, they were uniformly without honour in their own country. Mulk Raj Anand lived abroad for a number of years, Raja Rao still lives abroad. R. K. Narayan has always lived in India, though since the 1950’s he has travelled a lot. Apart from the obvious differences between them as writers, there are differences between the degree of each one’s success. Narayan, for example, is probably the most successful in America : on the European continent, where they still entertain the myth of the mystical Oriental, Raja Rao is a coterie figure : Mulk Raj Anand is mainly read in Russia and the Eastern European countries, where the roubles pile up around each of his books. Yet for the normally literate reader of English in India, all three are the same. They are all equal in splendour, because they have made names for themselves abroad—abroad being a term that embraces Connecticut as well as Kiev, and assumes both to be the same. Since the war, of course, there has been a flood of Indian novelists who produce in English. They are all fairly competent and fairly unremarkable. The exception is G. V. Desani, who is a kind of freak. Desani in 1948 produced one book, All about Mr. H. Hatterr, which seems to me a prose master piece. T. S. Eliot was one of those who praised it when it first appeared, but it was then forgotten for more than 20 years.

…

Desani, like all the others I have mentioned, won a reputation for himself in England, and he was accepted in India because of this. One reason for this uncritical acceptance of English critical praise seems to me the complete absence of any Indian criticism of English writing. This in itself is due perhaps to the initial fact of Macaulay’s system of education. The English told one, in the textbooks, what should be read and what shouldn’t. Ours not to question why. Naturally, therefore, it appeared to college instructors and school teachers that if and when Indian writers received the imprimature of an English publisher and the praise of English critics, they were OK. This lasted for a while, and then the tide turned. As with Professor Iyengar, so with most other Indian critics; every writer who was able to hobble as far as a printer’s shop and pay to be published was assured of a decent review, so as to enable the homegrown product to flourish.

This has led to a really dramatic fall of standards in Indian literature written in English.

…

…there have been others of promise, when they lived overseas, whose promise seems stifled when they come home. One of them is Adil Jussawalla. His first book, Land’s End seemed to me, and to many other poets in England, one of the most brilliant first books published since the war.

…

I have talked tonight about the fact that no proper criticism of Indian writing in English exists in India. There is no real literary magazine : there are no really professional critics. One reason, it seems to me, is that there are few really professional writers. Until quite recently, I lived purely on my earnings as a writer : in a sense I still do, since the function I perform for the United Nations is that of a professional writer. But very few writers in India have ever been professional in that sense—that is, that they exist and support their families on what their pens spit out and their typewriters cough up. Thus one has an enormous number of what could be called Sunday novelists and Sunday poets, and such writers deserve whatever criti cal appreciation is available : i.e. that of Sunday critics. Poets of potential like S. Santhi and Arvind Mehrotra have often spoken to me of the difficulty of obtaining proper criticism in India, and I would say this is one of the most gigantic drawbacks for any writer who works in English in India.

India International Centre Quarterly, Vol. 3, No. 2 (April 1976), pp. 143-156

16 March 2017

publishing house. It is often said poetry is too complicated to publish and to sell. It is subjective. Also many customers prefer to read poetry at the store and put the book back on the shelf. For many poets in India, self-publishing their poems has been popular. For generations of poets the go-to place was Writers Workshop begun by

publishing house. It is often said poetry is too complicated to publish and to sell. It is subjective. Also many customers prefer to read poetry at the store and put the book back on the shelf. For many poets in India, self-publishing their poems has been popular. For generations of poets the go-to place was Writers Workshop begun by  the late P. Lal. Some of the poets published by Writers Workshop included Vikram Seth, Agha Shahid Ali, Adil Jussawalla, Arun Kolatkar, Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, Jayanta Mahapatra, Keki Daruwalla, Kamala Das, Meena Alexander, Nissim Ezekiel, and Ruskin Bond. Some of the other publishing houses published occasional volumes of poetry too.

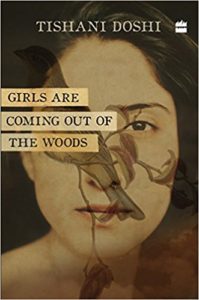

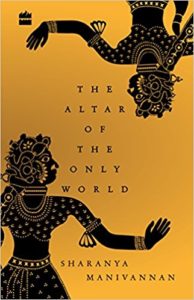

the late P. Lal. Some of the poets published by Writers Workshop included Vikram Seth, Agha Shahid Ali, Adil Jussawalla, Arun Kolatkar, Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, Jayanta Mahapatra, Keki Daruwalla, Kamala Das, Meena Alexander, Nissim Ezekiel, and Ruskin Bond. Some of the other publishing houses published occasional volumes of poetry too. some fine volumes of poetry which has included translations ( Mirabai and Tirukkal) and contemporary poets such as Jeet Thayil, Sridala Swami and Vikram Seth. Some years ago Harper Collins India published The HarperCollins Book Of English Poetry (ed. Sudeep Sen) and recently the excellent collection of poems by Tishani Doshi Girls are Coming Out of the Woods. Also that of Sharanya Manivannan ‘s The Altar of the Only World which is considered as well to be a very good volume. Penguin Random House India has a reputation for publishing good

some fine volumes of poetry which has included translations ( Mirabai and Tirukkal) and contemporary poets such as Jeet Thayil, Sridala Swami and Vikram Seth. Some years ago Harper Collins India published The HarperCollins Book Of English Poetry (ed. Sudeep Sen) and recently the excellent collection of poems by Tishani Doshi Girls are Coming Out of the Woods. Also that of Sharanya Manivannan ‘s The Altar of the Only World which is considered as well to be a very good volume. Penguin Random House India has a reputation for publishing good  volumes of poetry particularly of established poets such as 60 Indian Poets edited by Jeet Thayil. A volume to look forward to in 2018 will be Ranjit Hoskote’s Jonahwhale . The feminist publishing house Zubaan books published a fascinating experimental volume Andal: The Autobiography of a Goddess edited and translated by Priya Sarukkai Chhabra and Ravi Shankar.

volumes of poetry particularly of established poets such as 60 Indian Poets edited by Jeet Thayil. A volume to look forward to in 2018 will be Ranjit Hoskote’s Jonahwhale . The feminist publishing house Zubaan books published a fascinating experimental volume Andal: The Autobiography of a Goddess edited and translated by Priya Sarukkai Chhabra and Ravi Shankar.

than the other firms. In the past few months

than the other firms. In the past few months  alone some of their titles include Rohinton Daruwala’s The Sand Libraries of Timbuktu: Poems ; Manohar Shetty’s Full Disclosure: New and Collected Poems (1981-2017) ;

alone some of their titles include Rohinton Daruwala’s The Sand Libraries of Timbuktu: Poems ; Manohar Shetty’s Full Disclosure: New and Collected Poems (1981-2017) ;  C.P. Surendran’s Available Light: New and Collected Poems ; Guru T. Ladakhi’s Monk on a Hill: Poems ;

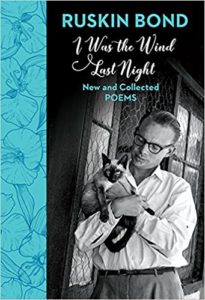

C.P. Surendran’s Available Light: New and Collected Poems ; Guru T. Ladakhi’s Monk on a Hill: Poems ;  Ralph Russell’s translations and edited by Marion Molteno A Thousand Yearnings: A Book of Urdu Poetry & Prose ; Ruskin Bond’s I Was the Wind Last Night: New and Collected Poems ; Michael

Ralph Russell’s translations and edited by Marion Molteno A Thousand Yearnings: A Book of Urdu Poetry & Prose ; Ruskin Bond’s I Was the Wind Last Night: New and Collected Poems ; Michael  Creighton’s New Delhi Love Songs: Poems . Later this year the Sahitya Akademi is publishing what looks to be a promising collection of poetry by “younger Indians”, edited and selected by noted poet Sudeep Sen.

Creighton’s New Delhi Love Songs: Poems . Later this year the Sahitya Akademi is publishing what looks to be a promising collection of poetry by “younger Indians”, edited and selected by noted poet Sudeep Sen. Having said that the self-publishing initiatives still continue. For instance a young poet and writer ( and journalist) Debyajyoti Sarma launched the i, write, imprint, press to publish poetry. Some of the poets published ( apart from him) include noted playwright Ramu Ramanathan, Uttaran Das Gupta, Sananta Tanty and Paresh Tiwari.

Having said that the self-publishing initiatives still continue. For instance a young poet and writer ( and journalist) Debyajyoti Sarma launched the i, write, imprint, press to publish poetry. Some of the poets published ( apart from him) include noted playwright Ramu Ramanathan, Uttaran Das Gupta, Sananta Tanty and Paresh Tiwari.

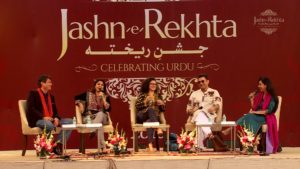

Sampurna Chattarji has been appointed the poetry editor of IQ magazine and is looking for submissions and hoping to be read as well! She writes about it on her blog. Another active space for poets is Poetry at Sangam which is edited by Priya Sarukkai Chhabra. It showcases poetry in English and translations as well as essays on poetics and news of new releases. Another vibrant space for poetry especially Urdu is the Jashn-e-Rekhta festival.

Sampurna Chattarji has been appointed the poetry editor of IQ magazine and is looking for submissions and hoping to be read as well! She writes about it on her blog. Another active space for poets is Poetry at Sangam which is edited by Priya Sarukkai Chhabra. It showcases poetry in English and translations as well as essays on poetics and news of new releases. Another vibrant space for poetry especially Urdu is the Jashn-e-Rekhta festival.

mike sessions etc where poets can recite/perform their work. In the past decade there has been a noticeable increase in these events whether informal groups that meet at local parks or coffee shops to more formal settings as a curated evening.

mike sessions etc where poets can recite/perform their work. In the past decade there has been a noticeable increase in these events whether informal groups that meet at local parks or coffee shops to more formal settings as a curated evening.